The only dates in the oral history were for Mbari, who was chief of his tribe from 1795 to 1797, and Katowa, who was chief 1450-97. The earliest ancestor, Mukunti-Muora, supposedly lived 4000 years ago. One thousand would be more realistic, and to get back from 1795 to 1450 in five generations is stretching it. There may, then, be some omissions of generations, or misremembered facts, but that makes this no different to the earliest oral pedigrees of the British Isles, which stretch back to Arthur, Brutus of Troy and the god Woden. This does not detract from their immense value because they undoubtedly do record the names of ancestors who really lived, and who are not recorded in any other fashion. Lose the oral history and these ancient memories will vanish irrevocably.

Such traditions should be treated with the greatest respect, but it is unrealistic to imagine that they can be strictly accurate. When using oral history as the basis for original, record-based research, you mustn’t be surprised if you find names, dates or places are given slightly (or sometimes wildly) inaccurately. I sometimes get my own age wrong by a year (I certainly can’t remember my telephone number all the time), so you should be prepared for this and, if you do not find what you are looking for under Thompson in 1897, see if what you want isn’t listed under Thomson in 1898 instead.

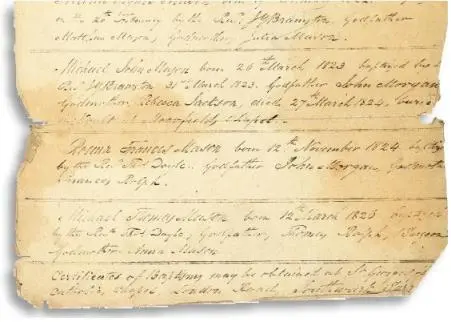

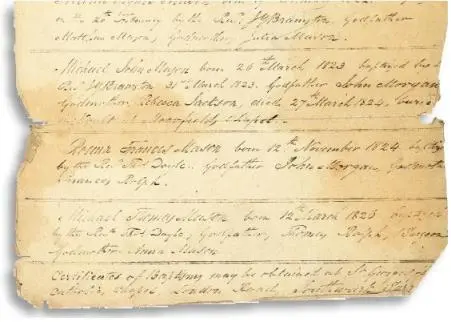

Family papers: lists of children’s dates of birth and baptism were often kept by families, especially before the start of General Registration in 1837.

In fact, you can’t trace a record-based family tree properly without developing a healthy scepticism for anything you are told, or indeed anything you read. There are deceptions and lies, of course. One family I helped, who were called Newman, discovered their ancestor had faked his own suicide and started a new life – as a ‘new man’, his original name having been something completely different. More often, though, discrepancies and inaccuracies arise through simple mistakes or lapses of memory. ‘Granny would never lie,’ said one client of mine, ‘so that birth certificate must be wrong.’ No, Granny didn’t lie, she just got her age slightly wrong. There’s a real difference.

Indeed, recording oral history often relies on interviewing the elderly. Sometimes, it’s the only time very old people have any proper attention paid to them, so be indulgent if they don’t reel out exactly what you want in ten minutes flat. Letter, telephone and email can all help you gain valuable information from your relatives, but if you can visit them, so much the better. It may seem a bind, but it’s often worth it and will become part of your store of memories to pass on to later generations. I once went all the way to Tours in France to visit Lydia Renault, a cousin of my mother’s. I arrived at 11am and, whereas her English relations would have offered me tea and some ghastly old biscuits, Lydia suggested whisky and Coca-Cola, which we drank on her balcony, overlooking the Loire, while she regaled me with tales of her family at the start of the 20th century.

That was an exception. If you get tea and stale biscuits, receive them with as great a semblance of delight as you can muster. If you are approaching someone you haven’t met before, make every effort to write and telephone in advance and make it absolutely clear you are after their invaluable knowledge, rather than their (usually less valuable) purse. Write down (or tape record) everything they say, as the seemingly irrelevant may later turn out to be the main clue that cracks the case. If they have difficulty remembering facts, ask them to talk you through any old photographs they may have – that often stimulates the synapses – and sometimes you may get more from them if you allow them to contradict you.

‘ What was your grandfather’s mother called ?’

‘ Oh, I don’t know .’

‘ I think it was Doris .’

‘ No, no, Doris was his sister. His mother was Milly !’

Another tip:if they can’t remember a date of, say, when someone died, try to get them to narrow down the period in which it could have happened.

‘ When did your great-grandmother die ?’

‘ I don’t know .’

‘ Well, do you remember her ?’

‘ Oh yes, she was at my wedding .’

‘ So she was alive in 1935. And was she at your first child’s christening in 1937 ?’

‘ Oh no, she died before then .’

Be sensitive, too, to changing social attitudes. Fascinating though it may be to you, the very elderly may not want to talk about their parents’ bigamous marriage, so if you want any information from them you must tread very carefully. One man’s black sheep, after all, is another’s hero.

Don’t forget, though, that younger relations of yours may have been told things by much older relations who are now dead. Equally – and here we leave the realms of oral history and move on a step – they, like the elderly, may have family papers and heirlooms. These come in so many forms: letters, school reports, memorial cards, passports, vaccination and ration cards, and so on, all crowned by the queen of all family papers, the family bible.

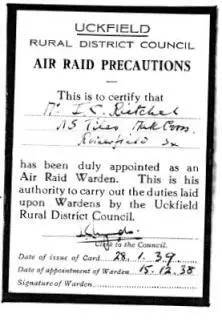

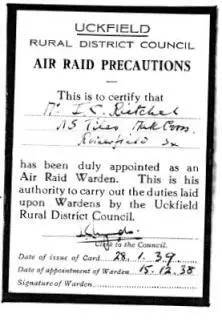

My grandfather’s air raid warden card. Note that he had been appointed before the war, in 1938.

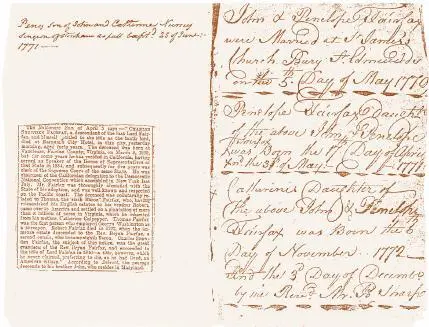

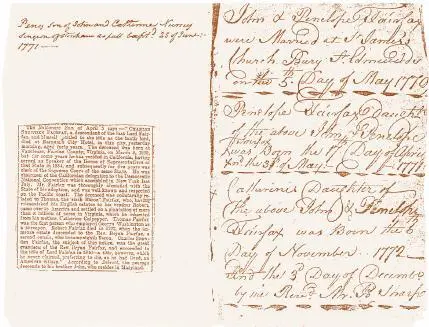

Some bibles can be centuries old, faithfully recording the births, marriages and deaths of each member of the family. The tip to finding family bibles is to trace down the female-to-female line of the family, as they are often passed from mother to daughter. Lost or unwanted ones (how can anybody not want a family bible?) often end up at car boot sales and genealogical magazines have been known to publish letters from well wishers who have found such a bible, describing its contents and volunteering to return it to the right family.

Whether it’s a family bible or a 70-year-old funeral bill, write down all the salient details (or, better still, photocopy everything) because such papers may contain clues that will only become useful to you long afterwards. Ignore such advice at your peril and, if you have to go back all the way to Wigan to have another look at your cousin’s grandmother’s address book you didn’t bother with ten years ago, don’t blame me.

Pages from the Fairfax family bible, which even includes an extra newspaper cutting.

Читать дальше