Cover

Title Page

Introduction

From Here to Obscurity

THE NO-GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY:

Obstacles to clear communication

The long, long trail a-winding: Circumlocution

An utterly unique added extra: Tautology

Witter + Waffle = Gobbledegook

Smart talk, but tiresome: Jargon

Saying it nicely: Euphemism

A word to the wise about Clichés

CLARITY BEGINS AT HOME:

How to improve your powers of expression

Circumambulate the non-representational: Avoid the abstract

Overloading can sink your sentence

Avoiding the minefield of muddle

Measuring the murk with the FOG Index

MAKING WORDS WORK FOR YOU:

A refresher course in Grammar and Punctuation

Punctuation needn’t be a pain: Stops, commas and other marks

The building blocks of good writing: Grammar without grief

Writing elegant, expressive English: The elements of style

Finding out: a word about dictionaries

HOW TO WRITE A BETTER LETTER:

Say what you mean; get what you want

Communicate better with a well-written letter

Relationships by post: Strictly personal

Protecting your interests: Complaining with effect

Staying alive: Employer and employee

Selling yourself: Creating a persuasive CV

Getting it and keeping it: Money matters

Writing in the new millennium: Word processing and E-mail

Index

Keep Reading

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Having picked up this book the odds are that you are a writer. Perhaps not a journalist or a novelist, but a writer nevertheless: of letters, memos, reports or even an occasional note to the milkman. You may keep a daily diary, or limit your output to greetings on Christmas cards once a year.

There is also a good chance that you suddenly have a need to write – a job application perhaps, a ticking off to the council, a heartfelt letter of condolence to a friend. Mind and pen poised, it slowly dawns on you that the gap between what you want to say and what hesitantly appears on the paper in front of you is as wide as an ocean.

Can you learn how to improve your writing skills? Can the art of good writing be taught? Despite some opinions to the contrary, the answer is yes. Writing is a highly personal accomplishment and while some will spectacularly develop native talents others will always find it a frustrating slog. But everyone is capable of enhancing their powers of written communication simply by learning and practicing the basic principles of clear, concise and coherent writing: planning, preparationand revision. Further improvement comes from observing examples of good and also bad writing, and your confidence as a writer will grow as you begin to appreciate that the English language is not a fearsome book of rules but an unrivalled communications tool that you can learn to use with the familiar ease of a knife and fork.

It is important at the outset that you are aware of the difference between speech and writing. You may think, ‘If only I could write as easily as I speak!’ Unfortunately it’s a wish that’s rarely granted. When we talk to someone face to face (or even over the phone) we can instantly correct mistakes and clarify misunderstandings, provide subtle nuances with a smile, a laugh or a shrug, add emphasis with a frown or tone of voice. But when we write something, we have just one shot to hit the bullseye so that whoever reads it understands it – precisely. Two millennia ago the Roman orator Cicero offered a pretty good tip: the point of writing is not just to be understood, but to make it impossible to be misunderstood.

The ability to write well is a valuable, life-enriching asset and Collins Good Writing Skills will help you towards this goal. Much of what you will read is the lifetime word wisdom of a veteran national newspaper sub-editor. Sub-editors are a newspaper’s front-line defence against inaccurate, ungrammatical, long-winded, repetitious and pompous writing – and thus the reader’s best friends. A group of Daily Telegraph sub-editors decided that a new shorter 60-word police caution was still too ponderous and proceeded to distil the same meaning into 37 words. Here is the 60-word version, devised by a Scotland Yard committee:

You do not have to say anything. But if you do not now mention something which you later use in your defence, the court may decide that your failure to mention it now strengthens the case against you. A record will be made of anything you say and it may be given in evidence if you are brought to trial.

And here is the revised, sub-edited version, clearer and shorter:

You need say nothing, but if you later use in your defence something withheld now, the court could hold this against you. A record of what you say might be used in evidence if you are tried.

No long or obtuse words, no flowery phrases – just crystal-clear prose that makes few demands on a reader’s time, holds the reader’s interest throughout and simply can’t be misunderstood. That is the kind of model this book recommends, although you will also be amused and appalled by dozens of other masterpieces of a vastly different kind – masterpieces of drivel and obscurity to drive home the sort of writing to avoid.

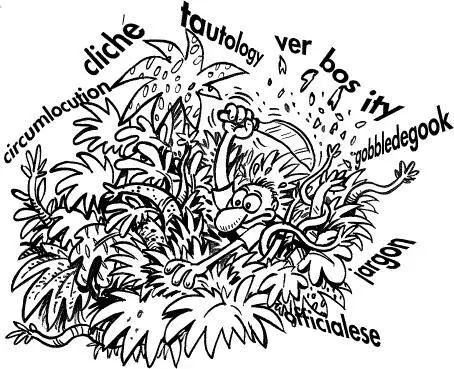

Into the jungle, with machete and pen

But first, let us be brave. We are about to hack our way through a jungle. The dense, tangled world of obscure and impenetrable language. Officialese. Circumlocution. Tautology. Gobbledegook. Jargon. Verbosity, pomposity and cliché. All the ugly growths that prevent us from understanding a piece of writing.

Perhaps the obstacle is a notice from our bank, the district council, the water, gas or electricity supply company, which for all we know might have a serious effect on our future. Or it may be a newspapaper or magazine article that makes us stop in mid-sentence to realise that we do not understand its meaning. Or perhaps it’s an advertisement for a job we might fancy . . . if only we knew what the wording meant.

This book, however, is not intended to help the baffled reader to fight through the thickets of spiky legalisms, prickly abstractions and tangled verbosity. Rather it is a guide to help you, the writerof the letter, memo, report or CV, to make sure your writing is clear of such obstacles to understanding.

Don’t be a sloppy copycat!

In business and bureaucracies, it is fatally easy to fall in with the writing habits of those around you: sloppy, vague and clumsy.

Yet most of us realise that a letter, memo or report from someone who knows how to write clearly and with precision is obviously more welcome, and read more keenly, than a dreary wodge of waffle and wittering.

Your own writing will be most effective when it is clear and direct. People who write in a straighforward way always shine out against the dim grey mass of Sloppies.

To be a good writer you have to write tighter

The usual advice on clear expression is: ‘Write as you speak’. But we have already concluded that unless you have special gifts or professional skills, this is virtually impossible. Perhaps the advice should be amended to: ‘Write as you speak – say what you mean, but make it tighter’.

Читать дальше