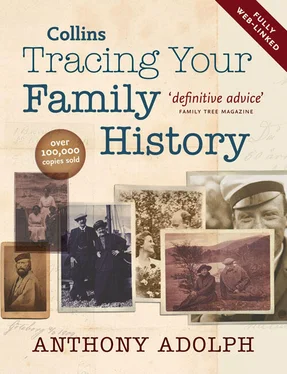

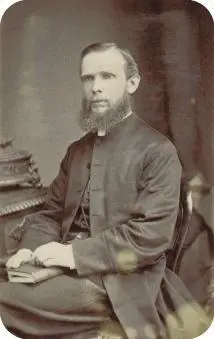

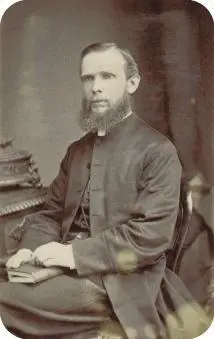

My mother’s great-grandfather, Rev. Patrick Henry Kilduff – one of a treasure trove of old photographs I was given by a distant cousin whom I had traced in the course of my research.

Millions of people, including you, are now actively investigating their origins, or at least thinking about doing so. This complete guide is intended to cover all the topics you will need to know about how to trace your family tree. You can start at the beginning, letting it guide you through the process of getting started and working back through the different types of records which should, given time and patience, enable you to trace your family tree back for hundreds of years. Or, if you are already a genealogist, you can use it as a reference book to identify and learn more about the vast array of different types of source that may be available for your research.

In some respects, this book follows the standards already set out by its predecessors, and I fully acknowledge my enormous debts to genealogical writers who blazed the trail before me, not least Sir Anthony Wagner, Mark Herber, Terrick FitzHugh, George Pelling, Don Steel, John Titford and Susan Lumas. In other respects, and within the parameters set by what is expected of genealogical reference books, I have tried to add to this my personal perspective, not least by drawing on my experiences in translating genealogy into radio and television.

A NEW BOOK FOR A CHANGING WORLD

In this book, I have tried to reflect the extraordinary changes that have recently injected new life into this most ancient of subjects.

DNA technology has escaped the confines of the laboratory and become readily available to anyone with even a modest research budget. Do not be deceived by the relative brevity of my chapter on the subject; its implications for genealogy are vast.

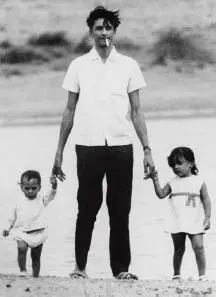

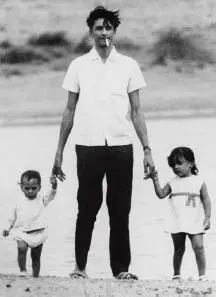

Although Britain has always been a multi-cultural nation, a barrage of prejudices and phobias meant that we have only recently started to uncover the full extent of our global roots. Only in the last two decades have the many white families with black or Asian ancestors been able to start investigating such connections. Only recently have they been permitted by society and, in some cases, their own attitudes, to look on their connections with other continents with fascination rather than shame. Equally, thanks to the post-war mass immigration of black and Asian families, there are now a very great number of British families with roots exclusively from overseas. But by far the greatest trend, resulting from relationships between the different ethnic communities in Britain, is the rise of generations with roots both in indigenous white Britain and in other continents.

Shilpa Mehta (on the right) with her father, Shailendra, and brother, Shayur, in Zambia before her family settled permanently in England (see here).

Other genealogical writers have not ignored this fact, but nor have they addressed the issue in any depth. I felt that, in writing a book for genealogists in modern Britain, it was appropriate to broaden its scope to acknowledge the vast number of readers whose ethnic English blood – if they have any at all – is only a small proportion of their total ancestral mix. I have not attempted to write a worldwide guide to tracing family trees but, while the focus of the book is on research in England, I have tried to show and remind readers how the same or similar sources can be located and used in the rest of the British Isles and in countries all around the world. Please note that, when I refer to records outside Britain, I do so by way of example: the absence of a reference to a type of record in a certain country does not mean that records are not there. The volume of material available for America requires a separate book and has therefore been omitted almost entirely.

The internet has changed genealogy by making different types of records more easily searchable and by creating new resources that never existed before, such as the GenesReunited website. If you are serious about tracing your family tree, I recommend you either acquire a computer, find a good library or café providing internet access, or are very, very nice to someone who is already connected to the web. While you should never trust anything on the internet without checking it in original sources, the amount of time you can save using the resources available online is enormous.

The Genes Reunited Website home page: www.genesreunited.co.uk

On a daily basis, new indexes and resources appear, change, grow or, in some cases, disappear from the great information super-highway that is the worldwide web. Website addresses are so helpful and important that I have provided the ones that are most useful at the time of writing, and made them an integral part of the text. However, the rate of change inevitably means that, by the time you read this book, some things will have changed and proposed new legislation even threatens to restrict access to some of the records described here. In most cases, though, change will only have been for the better in terms of more records becoming more easily accessible via index and databases.

I became a professional genealogist in 1992 after several years studying at the Institute of Heraldic and Genealogical Studies. During most of my career, first working for a well-known firm of genealogists and latterly with my own freelance business, I have spent more time establishing what sources are available to solve particular problems and commissioning record agents to search them, than actually being in archives myself.

Connections between the past and present. My great-great-aunt Louisa Havers (1832–1937) at Ingatestone Hall, Essex, in 1917, with her young cousin Philip Coverdale who, as an old man, took me under his wing and taught me how to trace family trees.

This is a course of action I wholeheartedly recommend to all readers of this book. Many people say, ‘But I want to do it all myself.’ Fair enough – and use this book to acquire a detailed knowledge of the sources and their whereabouts. But there are many cases where paying a record searcher in a different county (or on the other side of the world) for a couple of hours’ work can save a vast amount of time, travel and accommodation costs, especially if the source you identified turns out to have been the wrong one. Receiving positive results by post (or email) may not be quite as exciting as turning over a dusty page and finding an ancestor’s name but, frankly, most records are now searchable only by microfiche in record offices anyway. The time you will have saved having the search done can then be spent visiting the place where you have discovered your ancestor once lived. If you really want to do it yourself, though, don’t let me stop you. I merely offer a piece of personal advice.

Читать дальше