GETTING TO KNOW YOUR ANCESTORS

Throughout this introduction, I have referred to genealogy. There’s also a subject called family history. Essentially, genealogy is tracing who was who – the nuts and bolts of the family tree – while family history is more about finding out about the ancestors themselves, exploring their lives and working out how they came to do what they did and be who they were. That in itself then merges into the subject of biography. Once you have researched your family history in depth you will, in effect, have researched mini (or not so mini) biographies of your ancestors. Most, if not actually all, of the sources used by biographers are described in this book. Getting to know your ancestors can be a fascinating experience even if you do not (as people who have seen me in Antiques Ghostshow will know) want to roam into the world of psychics.

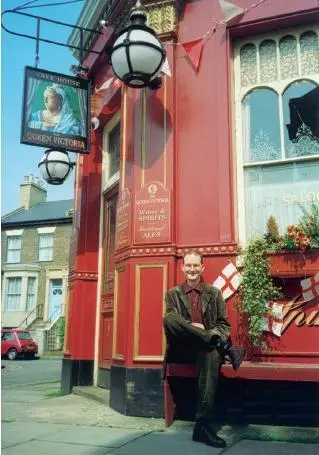

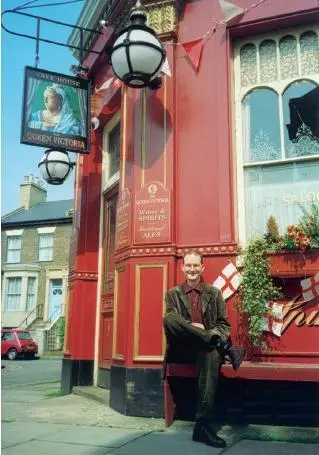

Filming the story of EastEnders ’ convulted family tree on location at Elstree, 2000.

The author filming ITV’s Lost Royals at the College of Arms with former BBC Royal Correspondent Jenny Bond and Norrow and Ulster King of Arms.

But, in investigating your family tree, please bear in mind there is a real distinction between your ancestors and the records in which they appear. I have known people to cherish birth certificates as if they were the spiritual embodiments of their forbears. They are not. Think of when you last looked at yours and what a nuisance it is when you generate records similar to those you use for tracing ancestry. Obtaining passports and driving licences is a chore: dealing with banks, lawyers, the Inland Revenue and social services is tiring and invariably annoying. Often, when you encounter an ancestor in a record, they, too, were probably vexed and annoyed through the making of it. Equally, useful though they are, many modern genealogy programs and charts require you to focus so much on dates of birth, marriage and death that you can easily forget that the people concerned actually had lives in the intervening years. The real ancestors stand back behind the dates and records they generated: bear that in mind and you won’t go far wrong in learning to understand them.

Tracing family trees is mainly about seeking records, but before you do that, there’s a great deal you may be able to learn from your own family – close as well as distant relatives. And whatever you find out, don’t forget to write it down. Start properly and avoid tears later!

CHAPTER ONE ASK THE FAMILY

With very few exceptions, nobody knows more about your immediate family than your immediate family. Yet the first steps in tracing a family tree are often ignored or skipped over in the headlong dash for illustrious roots and unclaimed fortunes.

Most people reading this will probably have made at least some sort of start at researching their family tree. This chapter gives structure to your first steps and, I hope, to all your research over years to come.

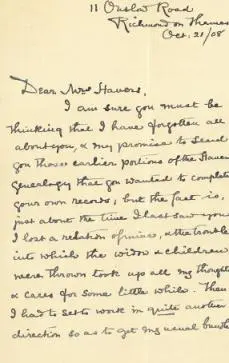

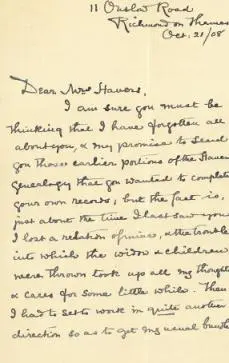

Family papers: a letter to my great-great-grandmother from her husband’s cousin, Mrs Dorthea Boulger (1908), concerning their family history.

However old you are, the very best way to start research is by writing down your own essential details, which are:

Date and place of birth

Date and place of birth

Your education, occupations and where you have lived

Your education, occupations and where you have lived

Religious denomination

Religious denomination

Anything interesting about yourself, which future generations may be glad you took the trouble to record

Anything interesting about yourself, which future generations may be glad you took the trouble to record

Date and place of marriage, and to whom (if applicable)

Date and place of marriage, and to whom (if applicable)

Date and place of children’s births and marriages (if applicable)

Date and place of children’s births and marriages (if applicable)

Then repeat the same process for your siblings, parents, their siblings, your grandparents and so on, adding details of when and where people died, if applicable.

One of the key elements here is write it all down because all this work will be to little avail if you do not record your findings.

Besides information on the living, you will soon start to record information on the deceased, as recalled by their children, grandchildren and so on. This is oral history – things known from memory rather than written records.

Originally, all family trees were known orally. In Britain, there are a handful of pedigrees of the ancient rulers of the Anglo-Saxons, Vikings, Britons, Gaels and Picts, which stretch far back into the past, and which are known now because they were later written down. They contain some palpable mistakes and grey areas, but they are greatly valued because they are pretty much all we have left. Sadly, cultures such as Britain that adopted widespread use of written records tend very quickly to lose the oral history that has been accumulated over the centuries. For much of the Third World, and the native cultures of the Americas and Australasia, this invasion of literacy has happened much more recently, and oral traditions are still strong. With the spread of literacy, though, oral history is under threat and will probably disappear altogether very soon; hence the need to write it down and make it available on websites such as Genes Reunited.

LIFETIMES : A RICH ORAL TRADITION

JUST BECAUSE very few written records were made in pre-colonial Africa does not mean that family trees cannot be traced. Benhilda Chisveto of Edinburgh knew her father was Thomas Majuru, born in 1953, and that his mother was Edith, but that was all. She then made enquiries about her family from older relatives still living in her native Zimbabwe, and was told the following family tree, dictated orally and perhaps never recorded on paper before.

Thomas Majuru was son of Mubaiwa, son of Majuru (hence the modern surname), who lived near Harare, and who was apparently the only survivor of his area when British forces invaded in 1897. He buried the dead and then sought refuge in Murehwa, where the family now live. He was son of Mukombingo. Before Mukombingo, the line runs back, son to father, thus: Kakonzo; Mudavanhu; Mbari; Taizivei; Barahanga; Jengera; Zimunwe; Katowa; Mhangare; Maneru; Dambaneshure; Chihoka; Chiumbe; Musiwaro; Mukwashahuue; Makutiodora; Diriro; Gweru; Makaya; Chamutso; Guru; Waziva; Misi; Chitedza otherwise called Chibwe Chitedza; Nyavira also called Nyabira; Mukunti-Muora.

Читать дальше

Date and place of birth

Date and place of birth