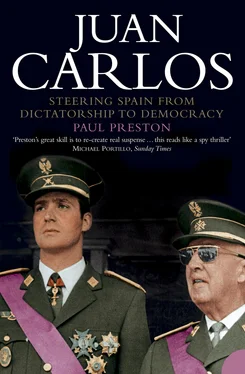

For Franco, and indeed many of his supporters within the Nationalist zone, the monarchy of Alfonso XIII was irrevocably stigmatized by its association with the constitutional parliamentary system. In his interview, he declared that, ‘If the monarchy were to be one day restored in Spain, it would have to be very different from the monarchy abolished in 1931 both in its content and, though it may grieve many of us, even in the person who incarnates it.’ This was profoundly humiliating for Alfonso XIII, all the more so coming from a man whose career he had promoted so assiduously. 27

The Caudillo’s attitude to the exiled King, and by implication, to the Borbón family, was underlined in a harshly dismissive letter sent to Alfonso XIII on 4 December 1937. The King, having recently donated one million pesetas to the Nationalist cause, had written to Franco expressing his concern that the restoration of the monarchy seemed to be low on his list of priorities. The Generalísimo replied coldly, insinuating that the problems which caused the Civil War were of the King’s making and outlining both the achievements of the Nationalists and the tasks remaining to be carried out after the War. Expanding on his ABC interview, the Caudillo made it clear that Alfonso XIII could expect to play no part in that future: ‘the new Spain which we are forging has so little in common with the liberal and constitutional Spain over which you ruled that your training and old-fashioned political practices necessarily provoke the anxieties and resentments of Spaniards.’ The letter ended with a request that the King look to the preparation of his heir, ‘whose goal we can sense but which is so distant that we cannot make it out yet’. 28 It was the clearest indication yet that Franco had no intention of ever relinquishing power, yet the epistolary relationship between Franco and the exiled King remained surprisingly smooth. (Indeed, in December 1938, Franco revoked the Republican edict that had deprived the King of his Spanish citizenship and the royal family of its properties.) Throughout the Civil War, after each victory, the Generalísimo had sent a telegram to Alfonso XIII and, in turn, received congratulatory messages from both the exiled King and his son. However, after the final victory, and the capture of Madrid, Franco had not done so. The outraged Alfonso XIII rightly took this to mean that Franco had no intention of restoring the monarchy. 29

If the future of Alfonso XIII’s heir was unclear to Franco, even less certain was that of his grandson, Juan Carlos. For the first four and a half years of his life, the boy lived with his parents in Rome. Soon after his birth the family moved from the modest flat on the top floor of the Palazzo Torlonia in Via Bocca di Leoni to the four-storey Villa Gloria, at 112 Viale dei Parioli in the elegant Roman suburb of Parioli. 30 This was a happy time for the Borbóns – a period during which it was possible to live as a relatively normal, as opposed to a royal, family. Juan Carlos’s younger sister Margarita was born blind on 6 March 1939. Even so, the degree of family warmth was limited. All three children were looked after by two Swiss nannies, Mademoiselles Modou and Any, under the supervision, not of their mother but of the Vizcondesa de Rocamora. The young Prince was often taken out for walks by his parents or by his nannies, sometimes to the Palazzo Torlonia, sometimes to the private park of the Pamphili family or to the park of Villa Borghese. Don Juan showed some affection for his eldest son, often carrying him in his arms when they visited Alfonso XIII at the Gran Hotel.

However, such signs of warmth were rare. The young Prince was soon being schooled in the harsh lesson that his central purpose in life was to contribute in some way to the mission of seeing the Borbón family back on the throne in Spain. Don Juan had already started to make demands that the child found difficult to meet. Miguel Sánchez del Castillo (a film actor working in Rome at the time) recalls that, on one occasion, Juan Carlos was given a cavalry uniform as a present from several Spanish aristocratic ladies. ‘An Italian photographer spent over an hour taking pictures of him. Don Juan Carlos, who was only four years old at the time, endured having to stand to attention on a table. When they finally took him to the kitchen and one of his nannies took his boots off, his feet had been rubbed raw, because the boots were too small for him. That is when he shyly started to cry. I later learnt that his father had taught him from a very young age that a Borbón cries only in his bed . 31

Two events soon disturbed the royal family’s tranquillity: the first was Queen Victoria Eugenia’s departure from Rome; the second was Alfonso XIII’s death. Victoria Eugenia had been spending increasing amounts of time in Rome. When Italy entered the Second World War on 9 June 1940, her position as an English woman became difficult and thereafter she divided her time between Lausanne in neutral Switzerland and the outskirts of Rome. She and her husband had been effectively separated for more than a decade but, as his health deteriorated, they spent more time together. In 1941, she returned to Rome in order to care for him, moving into the nearby Hotel Excelsior, where she stayed until his death. 32

Alfonso XIII died on 28 February 1941. A few weeks earlier, on 15 January, he had abdicated in favour of his son and heir, Don Juan. Speaking with the American journalist, John T. Whitaker, shortly before his end, the exiled King said, ‘I picked Franco out when he was a nobody. He has double-crossed and deceived me at every turn.’ 33 Alfonso was right. During his final agony, he kept asking whether Franco had enquired about his health. Pained by his desperate insistence, his family lied and told him that the Generalísimo had indeed sent a telegram asking for news. In reality, Franco showed not the slightest concern. At Alfonso XIII’s bedside, Don Juan made a solemn promise to his father to ensure that he was buried in the Pantheon of Kings at El Escorial. His promise could not be fulfilled while Franco remained alive, and Alfonso XIII’s body would remain in Rome until its transfer to El Escorial in early 1981. Franco was reluctant even to announce a period of national mourning for the King. He grudgingly agreed to do so only when faced with the sudden appearance of black hangings draped from balconies in the streets of Madrid. He limited himself to sending a red and gold wreath. Amongst the many other floral tributes that adorned Alfonso XIII’s funeral on 3 March 1941 was one from Juan Carlos. It was a simple arrangement of white, yellow and red flowers tied together with a black ribbon on which someone had sewn with a yellow thread the dedication ‘ para el abuelito ’ (for granddad). 34

The death of Alfonso XIII seemed, in all kinds of ways, to free Franco to give rein his own monarchical pretensions. He insisted on the right to name bishops, on the royal march being played every time his wife arrived at any official ceremony and planned, until dissuaded by his brother-in-law, to establish his residence in the massive royal palace, the Palacio de Oriente in Madrid. By the Law of the Headship of State published on 8 August 1939, Franco had assumed ‘the supreme power to issue laws of a general nature’, and to issue specific decrees and laws without discussing them first with the cabinet ‘when reasons of urgency so advise’. According to the sycophants of his controlled press, the ‘supreme chief was simply assuming the powers necessary to allow him to fulfil his historic destiny of national reconstruction. It was power of a kind previously enjoyed only by the kings of medieval Spain. 35

The 27-year-old Don Juan – now, in the eyes of many Spanish monarchists, King Juan III – took the title of Conde de Barcelona, the prerogative of the King of Spain. He faced a lifelong power struggle with Franco, who held virtually all the cards. For the task of hastening a monarchical restoration, he could rely only on the support of a few senior Army officers. However, the Falange was fiercely opposed to the return of the monarchy and Franco himself had no intention of relinquishing absolute power. In the aftermath of the Civil War, many conservatives who might have been expected to support Don Juan were reluctant to face the risks involved in getting rid of Franco. Accordingly, Don Juan began to seek foreign support. With an English mother and service in the Royal Navy, his every inclination was to look to Britain. But he was resident in Fascist Italy and the Third Reich was striding effortlessly from triumph to triumph. Accordingly, his close adviser, the portly and foul-mouthed Pedro Sainz Rodríguez, pressed him to seek the support of Berlin or at least secure its benevolent neutrality towards a monarchical restoration in Spain. 36 On 16 April 1941, Ribbentrop instructed the German Ambassador in Spain, Eberhard von Stohrer, to inform Franco – lest he hear of it through other channels – that Don Juan de Borbón had tried to contact the Germans through an intermediary in order to get their support for a monarchist restoration. The intermediary had approached a German journalist, Dr Karl Megerle, on 7 April and again on 11 April 1941. In the early summer of 1941, the Italian Ambassador in Spain, Francesco Lequio, recounted rumours circulating in Madrid that Don Juan was about to be invited to Berlin to discuss a restoration. Lequio reported that the intensification of efforts to accelerate the restoration were emanating from Don Juan’s mother – ‘an intriguer, eaten up with ambition’. 37

Читать дальше