On 26 January 1938, the child was baptized at the chapel of the Order of Malta in the Via Condotti in Rome. The choice of the chapel was made because of its proximity to the Palazzo Torlonia, where the reception took place. The baptism ceremony was conducted by Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, then Secretary of State to the Vatican, and the future Pope Pius XII. At the christening, the baby Prince’s godmother was his paternal grandmother, Queen Victoria Eugenia. His godfather in absentia was the Infante Carlos de Borbón-Dos-Sicilias, his maternal grandfather. As a general in the Nationalist army, at the time engaged in the battle for Teruel, he was unable to travel to Rome. He was represented at the baptism by Don Juan’s elder brother, Don Jaime. Very few Spaniards were able to travel to Rome for the occasion and the birth of the Prince went virtually unnoticed even in the Nationalist zone of Spain. 19

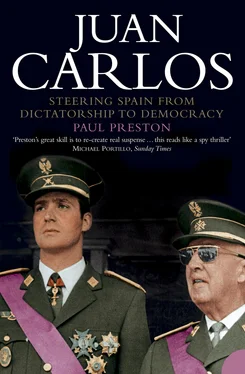

The boy was christened with the names Juan, for his father; Alfonso, for his paternal grandfather, the exiled King Alfonso XIII; and Carlos, for his maternal grandfather, Carlos de Borbón-Dos-Sicilias. Juan Carlos’s family and friends would, however, usually call him Juanito, at first because of his youth and later in order to distinguish him from his father. It was only after his emergence as a public figure that he began to use the name of Juan Carlos. There were, of course, political reasons behind the choice of the Prince’s public name. Don Juan told his lifelong adviser, the monarchisi intellectual, Pedro Sainz Rodríguez, that the choice was Franco’s. The idea may also have emanated from the conservative monarchist Marqués de Casa Oriol, José María Oriol, although the future King himself could not remember this with any certainty. 20 ‘Juan Carlos’ would distinguish the Prince from his father, Don Juan, and perhaps ingratiate him with the ultra-conservative Car lists whose pretender always carried the name Carlos. The elimination of his middle name, Alfonso, would certainly have been to Franco’s liking since it was central to the Caudillo’s rhetoric that it was the misguided liberalism of Alfonso XIII that had rendered the Spanish Civil War inevitable.

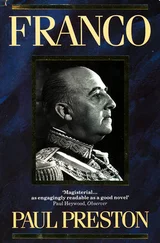

Don Juan de Borbón continued to harbour a desire to take part in the Nationalist war effort. He had written to the Generalísimo on 7 December 1936 and respectfully requested permission to join the crew of the battlecruiser Baleares which was then nearing completion: ‘… after my studies at the Royal Naval College, I served for two years on the Royal Navy battlecruiser HMS Enterprise , I completed a special artillery course on the battleship HMS Iron Duke and, finally, before leaving the Royal Navy with the rank of Lieutenant, I spent three months on the destroyer HMS Winchester .’ 21 Although the young Prince promised to remain inconspicuous, not to go ashore at any Spanish port and to abstain from any political contact, Franco was quick to perceive the dangers both immediate and distant. If Don Juan were to fight on the Nationalist side, intentionally or otherwise he would soon become a figurehead for the large numbers of monarchists, especially in the Army, who, for the moment, were content to leave Franco in charge while waiting for victory and an eventual restoration of Alfonso XIII. There was the danger that the Alfonsists would become a distinct group alongside the Falangists and the Carlists, adding their voice to the political diversity that was beginning to come to the surface in the Nationalist zone. The execution of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of the Falange, in a Republican prison had solved one problem, and Franco was now in the process of cutting down the Carlist leader, Manuel Fal Conde. He did not need Don Juan de Borbón emerging as a monarchist figurehead.

Franco’s response was a masterpiece of duplicity. He delayed some weeks before replying to Don Juan. ‘It would have given me great pleasure to accede to your request, so Spanish and so legitimate, to serve in our Navy for the cause of Spain. However, the need to keep you safe would not permit you to live as a simple officer since the enthusiasm of some and the officiousness of others would stand in the way of such noble intentions. Moreover, we have to take into account the fact that the place which you occupy in the dynastic order and the consequent obligations impose upon us all, and demand of you the sacrifice of desires which are as patriotic as they are noble and deeply felt, in the interests of the Patria … It is not possible for me to follow the dictates of my soldier’s heart and to accept your offer.’ 22 Thus, with apparent grace, he deflected a dangerous offer.

Franco also managed to squeeze considerable political capital out of so doing. He arranged for word to be circulated in Falangist circles that he had prevented the heir to the throne from entering Spain because of his own commitment to the future Falangist revolution. He also publicized what he had done and gave reasons aimed at consolidating his own position among the monarchists. ‘My responsibilities are great and among them is the duty not to put his life in danger, since one day it may be precious to us … If one day a King returns to rule over the State, he will have to come as a peace maker and should not be found among the victors.’ 23 The cynicism of such sentiments would be fully appreciated only after nearly four decades had elapsed, during which Franco dedicated his efforts to institutionalizing the division of Spain into victors and vanquished and failing to restore the monarchy. When the Baleares was sunk on 6 March 1938, Franco is said to have commented with an ironic smile, ‘And to think that Don Juan de Borbón wanted to serve on board.’ 24

In the meantime, in the autumn of 1936, believing that the military uprising would, if victorious, culminate in a restoration of the monarchy, Alfonso XIII had telegraphed Franco to congratulate him on his successes. In his suite in the Gran Hotel in Rome, the King kept a huge map of Spain marked with little flags with which he obsessively followed the progress of the rebel troops on various fronts. 25 In his confidence that Franco would repay earlier favours by restoring the monarchy, he misjudged his man. Had he and his son been a little more suspicious, they might have been alarmed to note that the newly installed Head of State had already begun to comport himself as if he were the King rather than simply the praetorian guard responsible for bringing back the monarchy. With the support of the Catholic Church, which had blessed the Nationalist war effort as a religious crusade, Franco began to project himself as the saviour of Spain and the defender of the universal faith, both roles associated with the great kings of the past. Religious ritual was used to give legitimacy to his power as it had to those of the medieval kings of Spain. The liturgy and iconography of his regime presented him as a holy crusader; he had a personal chaplain and he usurped the royal prerogative of entering and leaving churches under a canopy.

The confidence in himself and his office generated by such ceremonial was revealed when Franco celebrated the first year of his Movimiento . His broadcast speech was, according to his cousin, entirely written by himself. He spoke in terms which suggested that he placed himself far higher than the Borbón family, as a providential figure, the very embodiment of the spirit of traditional Spain. He attributed to himself the honour of having saved ‘Imperial Spain which fathered nations and gave laws to the world’. 26 On the same day, an interview with the Caudillo was published in the monarchist newspaper ABC. In it, he announced the imminent formation of his first government. Asked if his references to the historic greatness of Spain implied a monarchical restoration, he replied truthfully while managing to give the impression that this was his intention, ‘On this subject, my preferences are long since known, but now we can think only of winning the War, then it will be necessary to clean up after it, then construct the State on firm bases. While all this is happening, I cannot be an interim power.’

Читать дальше