William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2016

Copyright © Paul Preston 2016

Paul Preston asserts his moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

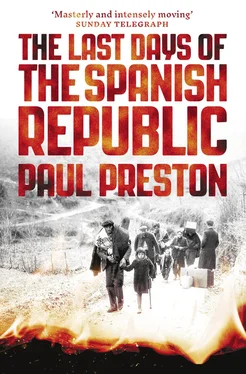

Cover image © Photo12/L’Illustration

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008163419

Ebook Edition © February 2016 ISBN: 9780008163426

Version: 2017-03-03

For Lala Isla

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgements

1 An Avoidable Tragedy

2 Resist to Survive

3 The Power of Exhaustion

4 The Quest for an Honourable Peace

5 Casado Sows the Wind

6 Negrín Abandoned

7 In the Kingdom of the Blind

8 On the Eve of Catastrophe

9 The Desertion of the Fleet

10 The Coup – the Stab in the Back

11 Casado’s Civil War

12 Casado Reaps the Whirlwind

Epilogue: Repent at Leisure?

Picture Section

Abbreviations

Notes

Illustration Credits

Bibliography

Index

By the Same Author

About the Author

About the Publisher

In the course of preparing this book, I have had the good fortune to rely on the advice on various issues of the following friends and colleagues. Michael Alpert, Javier Cervera, Robert Coale, Alfonso Domingo, Luis Español Bouché, Xulio García Bilbao, Carmen Gonzalez Martinez, Fernando Hernández Sánchez, Eladi Mainar Cabanas, Ricardo Miralles, Enrique Moradiellos, Óscar Rodríguez Barreiro, Cristina Rodríguez Gutiérrez, Sandra Souto and Julián Vadillo.

I am extremely grateful to the following friends for their help in the location of archival material. Laura Díaz Herrera for her invaluable help in Madrid and Ávila; Ángeles Egido León, José Manuel Vidal Zapater and Luis Vidal Zapater for permitting access to the unpublished memoirs of José Manuel Vidal Zapater; María Jesús González Hernández for help with the Causa General. Aurelio Martín Nájera as so often in the past was immensely generous in helping me with documents held in the Archivo Histórico of the Fundación Pablo Iglesias. Sir George Young and Lady Young kindly granted permission for the use of the papers of Sir George Young. My greatest debt is to Carmen Negrín and Sergio Millares Cantero for their unstinting assistance with both the papers and the photographs held in the Fundación Juan Negrín of Las Palmas.

I also want to put on record my thanks to Jesús Navarro, Juan Carlos Escandell and José Ramón Valero Escandell for an unforgettable day spent exploring ‘Posición Yuste’ (El Poblet), the houses at ‘Posición Dakar’ and the airfield (now a vineyard) of El Fondò in Monòver. Professor Valero Escandell also generously provided maps and photographs of the area of the Val de Vinalopó.

The gestation of this book, as with others in the past, was made especially rewarding thanks to my good fortune in being able to discuss many points of fact and of interpretation with my friends Helen Graham, Linda Palfreeman and Ángel Viñas.

This is the story of an avoidable humanitarian tragedy that cost many thousands of lives and ruined tens of thousands more. It has many protagonists but centres on three individuals. One, Dr Juan Negrín, the victim of what might be termed a conspiracy of dunces, tried to prevent it. Two bore responsibility for what transpired. One of those, Julián Besteiro, behaved with culpable naivety. The other, Segismundo Casado, behaved with a remarkable combination of cynicism, arrogance and selfishness.

On 5 March 1939, the eternally malcontent Colonel Casado, since May the previous year commander of the Republican Army of the Centre, launched a military coup against the government of Juan Negrín. Ironically, he thereby ensured that the end of the Spanish Civil War was almost identical to its beginning. As General Emilio Mola, the organizer of the military coup of 1936, its future leader General Francisco Franco and the other conspirators had done, Casado led a part of the Republican Army in revolt against the Republican government. He claimed, as they had done, and equally without foundation, that Negrín’s government was the puppet of the Spanish Communist Party (Partido Comunista de España, or PCE) and that a coup was imminent to establish a Communist dictatorship. The same accusation was made by the anarchist José García Pradas, who talked of Negrín personally leading a Communist coup. 1In that regard, it is worth recalling the judgement of the great American war correspondent Herbert Matthews, who knew Negrín well:

Negrín was neither a Communist nor a revolutionary … I do not believe that Negrín gave the idea of a social revolution any thought before the Civil War … Negrín retained all his life a certain indifference and blindness to social issues. Paradoxically, this put him in agreement with the Communists in the Civil War. He was equally blind in an ideological sense. He was a prewar Socialist in name only. Russia was the only nation that helped Republican Spain; the Spanish Communists were among the best and most disciplined soldiers; the International Brigade, with its Communist leadership, was invaluable. Therefore, Premier Negrín worked with the Russians, but never succumbed to or took orders from them. 2

A not unsimilar view was expressed by Negrín’s lifelong friend Dr Marcelina Pascua:

Was Negrín a Communist? How ridiculous! Not by a thousand miles. He was congenitally individualistic, utterly disinclined to follow a collective discipline or to put up with tight rules and regulations imposed by a political party or to follow the personal requirements that the instruments of marxism impose on their adherents. As far as any hero worship was concerned, the person that he admired most was Clemenceau (and not his contemporary Lenin) despite being fully aware of his repressive and reactionary policies against the trade unions and his persistent hostility to the French Socialists. I always interpreted Negrín’s veneration for ‘the Tiger’ in terms of his being seduced by the energy and efficacy that he demonstrated during the First World War. This explains the contradiction because what Negrín admired in Clemenceau was exactly the pragmatic determination to win the war that was what he aspired to do in the Spanish conflict.

According to Pascua, Negrín adopted as a private slogan Clemenceau’s remark that ‘Dans la guerre comme dans la paix le dernier mot est à ceux que ne se rendent jamais.’ 3

Casado claimed that he launched his coup because he was sure that he could put a stop to what was increasingly senseless slaughter and that he could secure the clemency of Franco for all but the Communists. Even if this was genuinely his selfless motive, and there is ample evidence to the contrary, he went about it in the worst way imaginable. In his dealings with Franco, he behaved as if he had nothing to bargain with. He seemed to be oblivious of the fact that Franco was obsessed with capturing Madrid, the very symbol of resistance. The Caudillo had failed to do so in November 1936 and had also been thwarted at the battles of Jarama and Brunete in February and July 1937. Unlike Negrín, who could threaten continued resistance when Franco was being pushed by his German and Italian allies for an early end to the war, Casado took the position that the war was already lost. His only hope therefore was the naive, and rather arrogant, belief that Franco would be susceptible to a vague rhetoric of shared patriotism and the fraternal spirit of the wider military family, as if somehow they were equals. 4In consequence, his action would actually cause massive loss of life.

Читать дальше