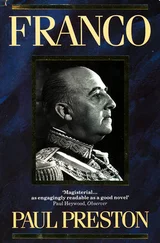

Pedro Sainz Rodríguez was beginning to suspect that not only would Franco not relinquish power before his death but that he would also pick as successor someone other than Don Juan. Of the various competing candidates, Juan Carlos would be preferable, but Don Juan had no desire to lose the throne even to his son. Accordingly, in his preparatory notes for the Pretender, Sainz Rodríguez argued that he must insist that: ‘the presence of the Prince must not be used to carry out manoeuvres suggesting that there is any agreement by which the order of succession can be altered.’ This threat came to be referred to by Sainz Rodríguez as ‘ balduinismo ’ – a reference to King Baudouin of Belgium who had ascended the throne in 1951 after the abdication of his father, Leopold III. 115

A grey-suited Franco arrived with a staff of 82 in a convoy of 11 Cadillacs. He was accompanied by the Ministers of Education and Public Works, as well as numerous security guards and aides, two cooks and a doctor. Apart from the driver, Don Juan was accompanied only by his private secretary, Ramón Padilla, and the Duque de Alburquerque. In contrast with their two previous meetings, the Caudillo manifested somewhat less interest in bringing Don Juan around to his point of view, having already eliminated him as a possible successor. In the event of ever needing to organize a rapid succession process, Franco had long since decided not to offer the throne to Don Juan. Rather, he would pick Juan Carlos and simultaneously ask Don Juan to abdicate, confident that he would agree rather than risk a public break with his son. For some time to come, he would astutely refrain from making that decision public, convinced that if he did so, Juan Carlos would side with his father. Nevertheless, the notion underlay his agenda at Las Cabezas which went no further than criticism of Don Juan’s collaborators and discussion of the details of the Prince’s remaining education. Don Juan, for his part, firmly expressed his concern at the way Franco was seemingly fostering the claims of other pretenders to the throne. It was no small triumph when he successfully pressed Franco to admit that some of them (certainly Don Jaime) were receiving financial support from the Secretary-General of the Movimiento.

Don Juan complained vigorously about the continuing anti-monarchist propaganda in Spain. In particular, he protested about a book, Anti-España 1959 , published in Madrid by an obsessive regime propagandist, Mauricio Carlavilla, who was also a secret policeman. The book denounced the monarchist cause as the stooge of freemasonry and a smokescreen for Communist infiltration, as well as insinuating that Don Juan himself was a freemason. Hundreds of copies had been sent by the Movimiento to people in official positions. Don Juan knew that the censorship apparatus would not have permitted the book to be distributed while Juan Carlos was resident in Spain without the Caudillo’s connivance. Now, Franco, who could plausibly have feigned ignorance, once again claimed evasively that he had no control over the press. He asserted that patriotic journalists must have seen the book as a reply to the memoirs of the monarchist aviator Juan Antonio Ansaldo, published in Buenos Aires in 1951. 116

This revealed that, even if Franco had not commissioned Carla-villa’s book, he certainly approved of its contents. Ansaldo’s ¿Para qué …? (For What?) had referred to Franco as ‘the usurper of El Pardo’ and attacked his failure to restore the monarchy as a betrayal of the sacrifices made in the Civil War against the Republic. Don Juan pointed out that there was little need for a reply to a book that had been banned in Spain. He went on to complain about the constant attacks to which the monarchy had been subjected by the Movimiento press over the previous 15 years. Implying again that the press was beyond his control, Franco shiftily attributed these criticisms to indignation over the 1945 Lausanne Manifesto on the part of journalists. Franco exposed his identification with Carlavilla’s views by referring bitterly to members of Don Juan’s Privy Council as ‘traitors’. He spent 25 minutes criticizing Pedro Sainz Rodríguez as a freemason, to which Don Juan replied that nothing that he had heard could persuade him that his piously Catholic adviser could be a mason. Somewhat rattled by this, Franco replied darkly that he knew of other masons in Don Juan’s circle including his uncle ‘Ali’ – General Alfonso de Orleans Borbón – and the Duque de Alba. When Don Juan burst out laughing at this, Franco finally desisted.

The remainder of the interview dealt with the education of Juan Carlos. Franco suggested that, while he would start off with a residence in El Escorial, he should soon move to the palace of La Zarzuela. Just outside Madrid, on the road to La Coruña, La Zarzuela was very near to Franco’s own residence at El Pardo. The interest shown by the Caudillo in this respect led Pemán to note in his diary, ‘La Zarzuela is being prepared for him and Franco is personally taking charge of its furnishing like a doting grandfather.’ Franco also suggested that Juan Carlos should work in Admiral Carrero Blanco’s Presidencia del Gobierno although nothing came of this suggestion. He agreed to the appointment of the Duque de Frías as the head of Juan Carlos’s household. There was then a detailed discussion of a list of members of the ‘study committee’ that was to oversee the Prince’s civilian education. Franco had brought a list with him, which included names such as that of Adolfo Muñoz Alonso, the Falangist head of the same censorship organization that had permitted the publication of Carlavilla’s book and of endless attacks on the monarchy. In this part of the conversation, Don Juan commented later, Franco was more flexible than in previous meetings: ‘he abandoned his usual dogmatic style of a schoolteacher dealing with an ignorant schoolboy.’ Franco, in contrast, told Pacón later that: ‘I said to Don Juan everything that I had to say to him and that he had to hear.’

Just before Franco rose to leave, Don Juan gave him the text of a proposed communiqué prepared by Sainz Rodríguez, in line with the notes that he had drawn up before the meeting. It stated that the talks had taken place in a cordial atmosphere and repeated once more that Juan Carlos’s education in Spain ‘does not prejudge the question of the succession nor prejudice the normal transmission of dynastic obligations and responsibilities’. It closed with the statement that ‘the interview ended with the strengthened conviction that the cordiality and good understanding between both personalities is of priceless value for the future of Spain and for the consolidation and continuation of the benefits of peace and the work carried out so far’. A visibly displeased Franco read the text and discussed it at length with Don Juan. He argued the text point by point. He protested at a reference to Juan Carlos as Príncipe de Asturias. Acceptance of that title would have signified public recognition that Don Juan was the King, so Franco slyly claimed that it was inadmissible on the grounds that it had not been ratified by the Cortes. Don Juan conceded the point.

The discussion grew more conflictive over the statement that Juan Carlos’s presence in Spain had no implications for the succession to the throne. Franco balked at this, saying it was ‘ duro ’ (harsh). Don Juan replied that this was, for him, the central issue and he insisted that it, or a similar sentence, must appear in the communiqué. The Caudillo continued to make objections until Don Juan said with studied weariness, ‘Well, General, if for whatever reason you find this note to be inopportune, I’m in no hurry. The academic year is well advanced, so I could keep the boy with me until October.’ At that, Franco accepted the text with alacrity. 117 Don Juan returned to Estoril, convinced that he had scored an important victory. On the following day, his staff went ahead and issued the agreed text in good faith. However, to their astonishment, the version that every Spanish newspaper was obliged to publish contained significant variants from Don Juan’s text. On arriving at El Pardo late on 29 March, Franco had unilaterally amended the agreed communiqué. 118

Читать дальше