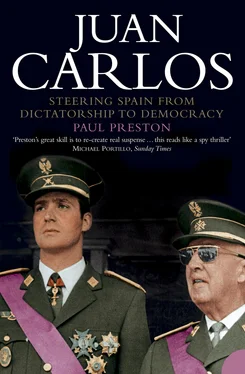

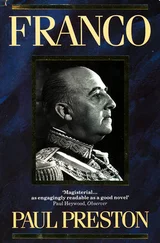

On the following day, Don Juan sent the Caudillo an explanatory note together with a new plan of studies. In it, Don Juan stated somewhat implausibly, ‘I want to emphasize that the delay in making the final decision that the Prince should not follow his civilian studies in Salamanca is not in any way a sudden improvisation nor mere caprice on my part.’ In justification of this statement, he alleged that Martínez Campos had gone ahead and made concrete plans despite his orders to the contrary. The plan itself, disparaging the University of Salamanca and its professors, was covered in the fingerprints of the same men who had confronted General Martínez Campos in Estoril. 106

Franco’s reply in mid-January was only mildly reproachful. He began by saying that he respected the Pretender’s decision while pointing out that the grounds on which it was based were highly dubious. He went on to say that further delay would be damaging to the Prince since it would break the habit of study, ‘to which I understand he is little inclined, preferring as he does practical activities and sport’. He then suggested that the Miramar palace in San Sebastián was totally unsuitable since it was too far removed from the great university centres and its damp climate would discourage hunting. Instead he proposed a location nearer Madrid, preferably the Casa de los Peces in El Escorial. ‘This would allow me, at the same time, to be able to see the Prince more often and to keep an eye on his education, which, as far as possible, I want to look after personally.’ He then announced that he had commissioned the Minister of Education, Jesús Rubio García-Mina, to draw up a full educational plan for the Prince and a team of professors from Madrid University to undertake the task. 107

Don Juan discussed this letter with Pemán, who saw Franco’s desire to see the Prince frequently as ‘rather alarming’. Before talking to Pemán, Don Juan had already replied promptly at the beginning of February, accepting the idea of residence in El Escorial, suggesting a group of professors from all over Spain who might take charge of his son’s education and naming the Duque de Frías, a non-political aristocrat who was best known as president of the Madrid golf club, as head of the Prince’s household. 108 Franco was quick to point out that the proposed teachers were likely to provide something approaching a liberal education. While that might be fine for ‘just any Spaniard’, something altogether more specific was required for the Prince. ‘It is necessary to complete the education of the Prince in those civilian subjects that are basic to his future decisions.’ He went on to explain that the coldly abstract education provided by a group of unworldly scholars would be entirely unsuitable. What was necessary, he declared, was a plan based on the principles of the Movimiento . From this he went on to say that he had noted that Don Juan had advisers who seemed to harbour the absurd idea that the monarchy could change the nature of the regime. As far as Franco was concerned, the contrary was self-evidently the case. The Caudillo had chosen the monarchy to succeed him precisely in order to prolong, not alter, his regime.

Franco had not been concerned while the Prince was in one or other of the military academies, ‘temples of patriotic exaltation and schools of virtue, of character-building, of the exercise of command, of discipline and of the fulfilment of duty’. ‘In the light of all this, and given the age of the Prince, I believe that the education of Juan Carlos over the next few years is more a question of State rather than one concerning a father’s rights and it is the State that should have priority in deciding the overall educational plan and the necessary guarantees.’ He suggested that the Prince’s director of studies should be a history professor who had fought in the Civil War with the Requetés , the ferocious Carlist militia that had played a crucial role in Franco’s war effort, was a member of the Opus Dei and was now a priest – a reference to the deeply conservative Federico Suárez Verdeguer. Should Don Juan disagree, Franco was contemplating putting the entire matter of the Prince’s education in the hands of the Consejo del Reino . Franco closed the letter with the ominous statement that he would consider a meeting to discuss the details only after certain misunderstandings had been cleared up, given that what separated them was a major issue of principle. 109

Don Juan’s reply was conciliatory. This reflected the role played in its drafting by the newly installed president of his Privy Council, José María Pemán. According to Pemán himself, he had been selected for the job precisely because he had no political ambitions of his own and he got on well with Franco. Now, to Don Juan’s text, he added what he called ‘the perfume so necessary for El Pardo’. 110 Don Juan seems not to have perceived that Franco’s growing interest in the boy was as his direct successor not as the eventual heir to his father. The letter began by recognizing that ‘it would be absurd for him not to receive an eminently patriotic education, inspired in the same loyalty to the fundamental principles of the Movimiento that he had imbibed in the military academies’. He recognized that the interests of the State should be paramount. He accepted Franco’s suggestion of Suárez Verdeguer and other professors. Regarding the issue of whether the monarchy would try to alter the Francoist State, he engaged in an extraordinary juggling act. Recognizing that some of his supporters wanted a parliamentary monarchy, while others such as the Carlists were virulently opposed to it, he still claimed that his loyalty to the principles of the Movimiento was unquestionable. He also called, rather optimistically, for Franco to make a declaration that: ‘the way in which the Prince’s education is taking place does not prejudge the question of the succession nor alter the normal transmission of dynastic obligations and responsibilities.’ Pemán had already begun some behind-the-scenes negotiations with a sympathetic Carrero Blanco. That they had borne fruit was revealed in Franco’s reply nearly four weeks later in which he offered a meeting on 21 or 22 March at the Parador of Ciudad Rodrigo near the Portuguese border. 111

News of the impending meeting stimulated rumours that major decisions about the future were imminent. Franco was now 67 and gossip was rife that his health was failing. On returning in his Rolls Royce from a hunting party in Jaén on 25 January 1960, a fault in the heating system had led to the rear of the car being filled with exhaust fumes. Noting his drowsiness, Doña Carmen had the presence of mind to order the car stopped before any serious harm was done. Wild rumours circulated within the regime, although Franco assured Pacón that he had suffered only a severe headache. Nevertheless, particularly after an announcement from the Rolls Royce Motor Car Company that exhaust gases could enter the car only if there had been deliberate tampering, the incident provoked speculation that something sinister had happened. 112 So, when news of the proposed meeting at Ciudad Rodrigo was broadcast on foreign radio stations and leaked in the press, gossip raced around Madrid that Franco planned to hand over power to Don Juan. Journalists, radio reporters and newsreel cameramen descended on the border town ready to flash the news to the world’s capitals. Deeply irritated, Franco postponed the meeting for seven days and changed the venue.

Franco was infuriated by the rumours that he assumed to have emanated from Estoril and the change of venue was meant as a reprimand for Don Juan. Nevertheless, given the eager talk about Franco’s mortality, enormous significance was read into Franco’s third meeting with Don Juan, their second at Las Cabezas, on 29 March 1960. 113 Las Cabezas had been inherited, on the Conde de Ruiseñada’s death, by his son, the Marqués de Comillas. Talking to Pacón before the meeting, Franco made it quite clear how little he planned to offer. He stated categorically, ‘as long as I have my health and my mental and physical faculties, I will not give up the Headship of State.’ 114

Читать дальше