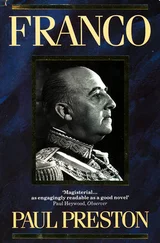

Arrese took his commission to be the preparation of an entirely Falangist future for the regime – one that would have no room for Don Juan nor even for Juan Carlos. The enthusiasm with which he went about his ambitious task would soon provoke a significant polarization of the Francoist coalition. Franco’s cabinet changes were ill-considered reactions to a deep-rooted split at the heart of his coalition. The Ley de Sucesión had been a cunning way of neutralizing regime monarchists and outmanoeuvring Don Juan. However, the prospect of a future monarchy, even a Francoist one, alienated the Falange. And Franco had few options but to cling to the Falange. If the Falange were weakened, the Caudillo’s fate would lie less in his own hands than in those of the senior Army officers who wanted an earlier rather than a later restoration of the monarchy. The situation required a complex balancing act and Arrese was more human cannonball than tightrope walker. The violent protests of Falangist students in February 1956 had been a symptom of a long death agony rather than of youthful vitality. With his mind elsewhere, occupied by the inexorable rise of Moroccan nationalism, and thus underestimating the seriousness of the crisis, Franco had responded instinctively by reasserting Falangist pre-eminence within his coalition. He was not controlling events but letting himself be driven by them. 32

Some months earlier, prominent Falangists had presented Franco with a memorandum demanding the swift implementation of their ‘unfinished revolution’. It was effectively a blueprint for a more totalitarian one-party State structure with no place for the monarchy of Don Juan. 33 Franco now seemed to be giving the green light for his new Secretary-General to implement the memorandum’s recommendations. Arrese’s plans were seen by Traditionalists, monarchists and Catholics as a totalitarian scheme which would block even limited pluralism under a restored monarchy. 34

With the help of Rafael Calvo Serer, the Conde de Ruiseñada, at the time Don Juan’s representative in Spain, elaborated a scheme to block Arrese’s plans by hastening the restoration of the monarchy. Ruiseñada was equally devoted to both Don Juan and to Franco. For some time, he had been in contact with General Juan Bautista Sánchez, the Captain-General of Barcelona, an austere and eminently decent man who was appalled at what he saw as the corruption of the regime. Now, the so-called ‘ Operación Ruiseñada ’ envisaged a bloodless, negotiated pronunciamiento , rather like that of General Miguel Primo de Rivera in 1923. The lead would be taken by the Barcelona garrison, with the agreement of the other Captains-General, and Franco would be persuaded to withdraw from active politics to the decorative position of ‘regent’. While the restoration of the monarchy was implemented, day-to-day running of the government would be assumed by Bautista Sánchez. The involvement of Bautista Sánchez – the most respected professional in the Armed Forces – helped secure the support of other monarchist generals against Arrese. Don Juan had considerable doubts as to whether this wildly optimistic scheme had any hopes of success but, concerned by Arrese’s plans, agreed to let it go ahead. 35

Needless to say, Franco’s intelligence services, which bugged most of Don Juan’s telephone conversations with Spain, were aware of what was being plotted. It was thus all the easier for Arrese, on a tour of the south with the Caudillo, to persuade him that a Falangist future rather than a monarchist one would be truer to his legacy. Franco gave vent to his impatience with Ruiseñada and Don Juan in speeches to which he gave, according to a delighted Arrese, ‘a twist of superfalangism and aggression that seemed to many to be announcing the beginning of the final triumphant era’. In Huelva on 25 April 1956, the Caudillo delighted his audience with an unmistakable and insulting reference to the monarchists and to Juan Carlos. He declared that: ‘We take no notice of the clumsy plotting of several dozen political intriguers nor their kids. Because if they got in the way of the fulfilment of our historic destiny, if anything got in our way, just as we did in our Crusade, we would unleash the flood of blueshirts and red berets which would crush them.’ 36 At a huge meeting of Falangists in Seville on 1 May, he passionately denounced the enemies of the Falangist revolution. In a passage of his speech that seemed to be directed at Don Juan personally, he referred openly to his own near-monarchical status. Describing the Movimiento with himself at the pinnacle, he said: ‘We are a monarchy without royalty, but a monarchy all the same.’ Stating that national life had to be based on the ideals of the Falange, he declared that: ‘the Falange can live without the monarchy but what could not survive is a monarchy without the Falange.’ 37 Many Francoists were happy enough to go along with the Movimiento as long as it remained a vague umbrella institution, but defining it so closely to Falangist terms led many to re-evaluate their own preferences.

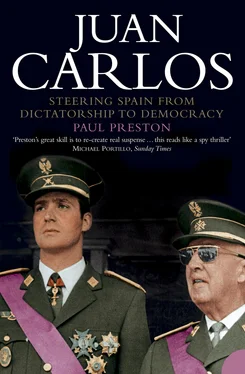

One of them, the Minister of Justice, the Traditionalist Antonio Iturmendi, was sufficiently alarmed to commission one of his brightest collaborators to produce a critical analysis of Arrese’s preliminary sketches for constitutional change. It was a decision that would have considerable impact on the later trajectory of Juan Carlos. The man given the job was the Catalan monarchist and professor of administrative law, Laureano López Rodó. His report was to be a blueprint of his growing commitment to the cause of Juan Carlos. 38 The deeply religious and austere López Rodó, who would quickly rise to a discreet but considerable eminence, was a typical senior member of Opus Dei, quietly confident, hard-working and efficient.

More immediately significant, at the beginning of July 1956, General Antonio Barroso Sánchez-Guerra protested to the Caudillo about Arrese’s activities. He was just about to replace Franco’s cousin Pacón as head of the Caudillo’s military household. Along with two other monarchist generals, one of whom may well have been Bautista Sánchez, he discussed with Franco a version of the Operación Ruiseñada , in which a military directory would take over and hold a plebiscite on the issue of monarchy or republic, in the confident expectation that such a consultation would produce support for the monarchy. 39 While hardly likely to go along with Operación Ruiseñada , Franco was sufficiently sensitive to military opinion to begin gradually to restrain Arrese. Nonetheless, when he made a speech to the Consejo Nacional de FET y de las JONS on 17 July 1956, the 20th anniversary of the military uprising, he used notes provided by Arrese, ‘to ensure that he did not say anything, either influenced by other sectors of the Movimiento or in an effort to calm liberal and monarchist anxieties, that might put us in an embarrassing situation later on’. 40 Essentially a long hymn of praise to his own achievements, although not without passing praise for Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, the speech reassured Falangists that a future monarchical successor would not be allowed to use his absolute powers to bring about a transition to democracy. 41

Unaware that the tide was turning against him, Arrese went ahead with his plans, distributing a draft to members of the Consejo Nacional , the supreme consultative body in the Francoist firmament. Although his text recognized Franco’s absolute powers for life, it left the decision as to his royal successor at the mercy of the Consejo Nacional and the Secretary-General of the Falange. When the text was distributed, there was uproar in the Francoist establishment, and monarchists, Catholics, archbishops and generals joined together in outrage. There were protests from three cardinals, a government minister (the Conde de Vallellano, Minister of Public Works) and several generals, at what seemed to be an attempt to give the Movimiento totalitarian control over Spain and block the return of the monarchy. 42 By early January 1957, Arrese had been obliged to dilute his text sufficiently to satisfy his military and clerical opponents. 43

Читать дальше