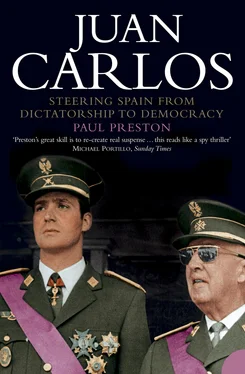

It was Juan Carlos’s fervent wish to be allowed to get on with life as an ordinary cadet. ‘You can avoid a lot of problems by getting lost in the crowd.’ That was rendered impossible because the campaign against Don Juan in the Movimiento press remained intense during this period. Juan Carlos found these constant attacks on his father upsetting. Some of his fellow cadets would derive a malicious pleasure from quoting the insinuations of the press. On several occasions, Juan Carlos was sufficiently provoked by remarks that his father was a freemason or a bad patriot (for serving in the Royal Navy) to get involved in fights. These were organized furtively in the stables at night, possibly even with the complicity of the teaching staff. When Juan Carlos eventually complained to Franco about the media’s attacks on his father, the Caudillo replied, with his habitual cynicism, that the Spanish press was independent and that he had no influence over it. He stated that, ‘it was impossible to do anything, since the press was free to express its opinions.’ As Juan Carlos commented, ‘it was such an outrageous lie that all I could do was laugh.’

Recounting this later, Juan Carlos was rather benevolent with regard to Franco. Reflecting on the fact that the Caudillo saw in Don Juan a dangerous liberal, he commented, ‘When my father said “I want to be King of all Spaniards,” Franco must have translated this as “I want to be King of the victors and of the vanquished.”’ This puzzled Juan Carlos, because of the fact that Franco knew full well that Don Juan had tried to join the Nationalist forces against the ‘reds’. Referring to the cunning letter with which Franco had refused Don Juan’s offer, Juan Carlos commented rather uncritically, ‘On that occasion, the General wrote my father a very beautiful letter to thank him for his gesture. In it, he told him that his life was too precious for the future of Spain and that he forbade him to risk it at the battle front. Why was my father’s life precious if not because he was the heir to the crown? But, what can you say … that was the General for you. At times, putting up with him was very difficult. But, as you know, I had totally convinced myself that to achieve my objectives I had to put up with a lot. The objective was worth the trouble.’ The objective was the re-establishment of the Borbón family on the throne. 5

Despite these occasional outbursts of hostility towards his father, Juan Carlos would later recall his years in the military academies as amongst the happiest in his life. In a brief letter to the readers of a Spanish magazine which published, in 1981, a feature on this period, he wrote: ‘I remember my years at the military academies with genuine satisfaction and nostalgia … Now that my post and occupations leave me hardly any time or freedom, I often think back to that distant period in which my life evolved in a way so different from the current one.’

Above and beyond the special status, of which none of his fellow students could remain ignorant, Juan Carlos soon became a genuinely popular cadet. His contemporaries at the academies would later describe him as a ‘sensational companion’, outgoing, generous, particularly gifted at sports and endowed with an extraordinary memory. His ability to remember people’s names and faces would later enable him to recognize and greet comrades and teachers whom he had not seen in years. He had a good sense of humour and enjoyed playing practical jokes on his friends. He often participated, for instance, in the food fights that occasionally erupted at lunch times in the refectory. Academically, he was said to be of ‘average intelligence’, but above average in ‘general knowledge’, foreign languages, tactical thinking and military ethics. He struggled with mathematics, which was ‘the subject dreaded by all’. Juan Carlos was also perceived as being deeply religious: every day, he would get up before reveille in order to attend the voluntary, early morning mass.

When it came to friendships, the Prince necessarily had to be careful, making every effort to avoid the creation of a circle of admirers or sycophants who wanted to be with him only out of self-interest. He tried to get to know as many people as possible, which was made easier by the fact that the class groups changed every term. He was aware of the dangers of nepotism: indeed, at the end of his military training, he refused to use his influence in order to get plumb postings for his friends from the academies. He did, however, strive to keep in touch with his old companions, attending and often even organizing reunions. 6 Not all of his contemporaries were keen to flatter him: ‘Some thought that I was a spoilt brat, spoiled by destiny, a daddy’s boy, the inhabitant of another planet. I had to use my fists to become one of them.’ 7 To this end, he encouraged his peers to treat him with considerable informality. His close friends called him ‘Juan’ or ‘Juanito’, or even ‘Carlos’, whilst his other companions addressed him with the informal ‘ tú ’ and jokingly called him SAR, an abbreviation of ‘ Su Alteza Reaf ’ (His Royal Highness). 8

This easy-going informality outraged General Martínez Campos who visited the academy each weekend to review the Prince’s progress and have lunch with him. On one occasion, Martínez Campos allowed his tutee to invite a couple of his academy friends to join them for lunch. During the meal, when he heard one of these friends call the Prince ‘Juan’, he exploded. Red-faced with fury, he leapt to his feet, knocking his chair out of the way and shouted at the culprit: ‘Gentleman cadet! On your feet and stand to attention! How dare you, gentleman cadet, address informally and by his first name someone that I, a Lieutenant-General, address as His Royal Highness!’ Unsurprisingly, Juan Carlos was never again able to convince his friends to join him for lunch with Martínez Campos. 9 Juan Carlos soon came to dread these visits from his supervisor, turning pale and trembling as the meeting time came closer. 10

The teaching staff at the academy addressed Juan Carlos as ‘Your Highness’ and, at roll-call, he was referred to by his full title – ‘His Royal Highness Juan Carlos de Borbón’. That aside, in so far as it could be put aside, Juan Carlos was, according to his contemporaries, treated by the teaching staff just like any other student. He was disciplined like any other cadet when he broke the rules. Once, for instance, he was put under house arrest for being caught smoking indoors. The Prince was subject to the same timetable as the other students, which left them very little free time. Reveille was at 6.15 a.m., although Juan Carlos rose earlier in order to attend mass. By 6.30 a.m., all cadets had to be standing to attention in the corridors, where roll-call took place. The young men were then allowed to take their showers – in water usually either freezing or so hot as to be almost unbearable. Individual study time followed, then lessons, lunch, a half-hour break, further lessons, another half-hour break and dinner. According to his contemporaries, no one was ever asked by the teaching staff to make allowances for the Prince or to treat him with special deference. In his first year at Zaragoza, Juan Carlos was thus subjected to the same ‘ novatadas ’ (initiation tests) and other pranks as the other newly arrived students. Years later, he remembered not only many of the pranks played on him on his arrival at Zaragoza, but also their names: ‘I had to undergo everything. I had to do the “reptile” on the bedroom floor. I slept with the “nun” [with a sabre resting on his chest]. They “X-rayed” me [they made him sleep between two planks from the bedside table]. I also had to let them “clay pigeon shoot” me [he was left in a room blindfolded and, when he attempted to leave, he was battered with pillows].’ 11

Читать дальше