He just needed an in.

And what do you know: At a dinner party at Gary and Rocky Cooper’s house in the summer of ’58, there was Peter.

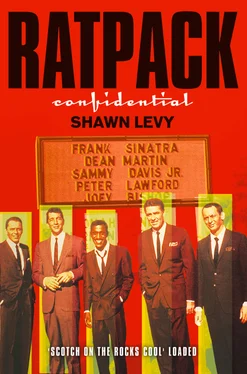

Frank had seen Lawford among his in-laws at the Democratic convention two years earlier; he was working, incongruously, with Bobby, trying to gain support from the Nevada delegation, which was run by Peter’s sometime Desert Inn boss, Wilbur Clark.

At the time, even though they’d been chummy at MGM in the forties, Frank was carrying a grudge against Peter—a misunderstanding about a woman. In late ’53, after she and Frank had split, Ava Gardner had a drink with Peter at an L.A. nightspot. When Louella Parsons reported the little tête-à-tête, Frank went bonkers, calling Peter at two in the morning and shouting at him, “Do you want your legs broken, you fucking asshole? Well, you’re going to get them broken if I ever hear you’re out with Ava again. So help me, I’ll kill you.”

Peter was terrified: “Frank’s a violent guy and he’s good friends with too many guys who’d rather kill you than say hello.” He asked a friend to intervene, and when Frank realized that it really was just an innocent drink, he cooled off. But he didn’t bother with Peter until he’d become a Kennedy, and even then grudgingly. Pat Kennedy, presuming with some reason to install herself as a society queen in Hollywood, had tried for years to have Frank attend some or other event; he had always brusquely refused her.

But as her brother’s star rose, and as Frank’s interest in politics merged subtly with his naked ambition, Peter’s near-trespass didn’t seem so awful. So it came to pass that on that fateful night at the Coopers’, with Peter working late at the studio on his Thin Man TV series, Pat found herself rapt in conversation with Frank, who had gone out of his way to break the ice with her. Dolly Sinatra’s boy, ever aware of who held the power, knew that she could provide quite a high level of access to what was clearly a growing political concern.

When Peter arrived at the party—bandaged after an injury on the set—he was amazed to discover his wife and Frank amiably chatting. He quietly took a seat at the table, not knowing what sort of greeting to expect. Frank looked at him, then looked back at Pat and said, “You know, I don’t speak to your old man.” The two of them laughed, and Peter did, too, a beat later, when he realized he’d been forgiven.

Within a few months, a suddenly intimate relationship formed between Peter and Frank. When Pat had a daughter that November, the child was christened Victoria Francis—the first name in recognition of her Uncle Jack’s reelection to the Senate that day, the second in recognition of Frank.

The following year, vacationing together in Rome, Frank actually apologized to Peter for the way he’d blown up over Ava: “Charlie, I’m sorry. I was dead wrong.” It was the rarest of moments: another smile of fate upon Peter Lawford.

He and Frank became fast pals, frat brothers with nicknames, booze, broads, matching cars. He got work: the Pacific theater war movie Never So Few , his first picture in six years, came his way strictly because Frank insisted on it—and at a price that made MGM choke, also at Frank’s insistence. The two became partners in a Beverly Hills restaurant, Puccini, and served spaghetti and chops to the stars; Frank was so glad to have Peter on board that he put up both halves of the seed money.

And Frank had his avenue to Jack Kennedy. Peter admitted that he and his wife “were very attractive to Frank because of Jack.” Sure enough, once he was connected, Frank leapfrogged over the guy he came to call “the brother-in-Lawford” and ingratiated himself with both Jack and Old Joe.

Indeed, though his cavorting with Jack was famous, Frank may have been closer to the father, the primary source of money and power in the family and the one most familiar with the courtship of disreputable outsiders, whether they were mobsters, corrupt politicians, larcenous power brokers, or temperamental pop stars. Joe had, it was said, prevailed on Sam Giancana to help erase public records of Jack’s annulled 1947 marriage to a Florida socialite; he called upon the Chicago don again in the late fifties to smooth things between himself and Frank Costello when Kennedy’s reluctance to recognize his obligations to the New York mobster almost resulted in a contract on his life; later, during the 1960 presidential campaign, he was seen dining at a New York restaurant with a select group of top mobsters from around the country. Jack may have had all the buzz, but Joe was, in Frank’s eyes, the real man of the world in the family.

If Jack didn’t inherit his father’s intimacy with the ways of men of dark power, he had plenty of Joe’s lustful wantonness. In this, Frank made a perfectly agreeable playmate, especially when it came to the young senator’s favorite diversions—women and gossip. The two began partying together soon after Frank reconciled with Peter—“I was Frank’s pimp and Frank was Jack’s,” Lawford ruefully recalled. “It sounds terrible now, but then it was really a lot of fun.”

Whenever Jack came to the West Coast for fund-raising or other official duties, he made sure to hook up with Frank, more often than not with Peter in tow. They didn’t hide their budding friendship from the press: “Let’s just say that the Kennedys are interested in the lively arts,” Peter told a reporter, “and that Sinatra is the liveliest art of all.”

In November 1959, Jack extended a trip to Los Angeles by spending two nights at Frank’s Palm Springs estate. Frank got a huge belly laugh out of him by introducing him to his black valet, George Jacobs, and suggesting that the senator ask the mere servant about civil rights. “I didn’t like niggers and I told him so,” Jacobs remembered. “They make too much noise, I said. The Mexicans smell and I can’t stand them either. Kennedy fell in the pool he laughed so hard.”

Fun over, Jack had to return East, even though he would’ve just loved the next night, when Frank, joined by Joey Bishop, Tony Curtis, Sammy Cahn, Jimmy Durante, Judy Garland, and about a thousand others toasted Dean at the Friars Club. But he made a mental note to catch up with them the next time they’d all be together: the following winter in Las Vegas when they’d be making a movie.

It was one last bit of patrimony thrown Peter by his new best friend. Frank had taken a literary property off his hands: Ocean’s Eleven , a movie about a group of World War II vets who hold up Las Vegas.

Never So Few , Peter’s comeback picture, was shaping up into quite a party, maybe even bigger than Some Came Running. After rescuing Peter from TV, Frank used his weight to get Sammy a $75,000 part. (The producers had balked, “Frank, there were no Negroes in the Burma theater.” And Frank shot them down: “There are now.”)

To Sammy, it only seemed proper: With his talent, youth, versatility, vitality, and powerful friends, he was on the verge of being the biggest star of his time.

Then he stumbled. Speaking to a radio interviewer in Chicago, he trashed Frank, just trashed him: “I love Frank and he was the kindest man in the world to me when I lost my eye in an auto accident and wanted to kill myself. But there are many things he does that there are no excuses for. Talent is not an excuse for bad manners—I don’t care if you are the most talented person in the world. It does not give you the right to step on people and treat them rotten. This is what he does occasionally.” (As a coup de grâce, asked who the number one singer in the country was, Sammy replied that it was he. “Bigger than Frank?” “Yeah.”)

Читать дальше