Peter was never formally schooled and spoke only broken English for much of his childhood (French was, in a way, his native tongue); he was probably some sort of dyslexic, but he had to diagnose his problem—and treat it—on his own. Tutelage in nonscholastic matters, unfortunately, was provided him by others: At nine, he became a target of pedophiles, both male and female—a horror that lasted through his teens.

May knew nothing of Peter’s tortures, concerning herself instead with cultivating his desire to playact and perform. A perfect Little Lord Fauntleroy, Peter charmed crowned royals, ships’ captains, film directors, and journalists alike with his impeccable manners and precocity. At eight, he played a part in Poor Old Bill , an English kiddie film. He acquitted himself so well that he surely would’ve received more offers of work had not the general put his foot down—“My son a common jester with cap and bells, dancing and prancing in front of people!”—and hied the family off on an extended sojourn to India and the South Pacific.

It would be seven years before Peter had another chance to act, and then only because of a freak accident that maimed and nearly crippled him. Returning to his parents’ French Riviera home after a game of tennis, he shattered a window-pane and sliced his right arm straight through to the bone. The first doctor to examine the arm declared it unsalvageable. Counseled to amputate, May responded with aplomb—“Fuck off, doctor!”—and found a physician willing to stitch Peter’s muscles back together. The arm was saved. To combat the lingering pain and stiffness, however, the Lawfords were advised to relocate Peter to a dry climate—Los Angeles, say. Although the arm would never fully heal (in its natural state of relaxation, Peter’s right hand was clawlike), it gave him, perversely, his ticket to success.

He found bit parts right away, but it would take five more years of on-again, off-again work before Peter was granted a full contract by MGM. But when the deal was done, it was as near as a twenty-year-old could imagine to a golden ticket from God Almighty.

May and the general thrived as well, becoming staples of the British expatriate community in Los Angeles and earning a reputation as grand old eccentrics among the Hollywood crowd: Frank once asked May about her son, and she responded in what she thought was perfect Hollywoodese—“Peter? That schmuck!”—bringing him to his knees with laughter.

Aside from affording May a society in which she could act the grande dame, Hollywood gave Peter the opportunity to chase every famous skirt in the world: Lana Turner, Rita Hayworth, Anne Baxter, Judy Garland, June Allyson, Ava Gardner … you name her. His appetites weren’t necessarily orthodox: He had chances, for instance, to bed both Elizabeth Taylor and Marilyn Monroe, but refused the former because she had what he considered “fat thighs” and the latter because her living room was dotted with chihuahua poop when he rendezvoused with her. But he was always being floated in the gossip pages as some pretty young thing’s fiancé, and he was swain enough to travel with sexual gear—towels, blankets, mouthwash, changes of clothes—in his car.

Despite this impressive record of cocksmanship, though, he was constantly plagued by rumors of homosexuality. He was chummy with Van Johnson and Keenan Wynn, and scuttlebutt put all three of them in bed together with Wynn’s wife, Evie (who, in fact, married Johnson within hours of getting a divorce from Wynn). Later on, stories circulated about trysts with other young actors, of loitering in notorious public men’s rooms, of all-boy parties in Hawaii, of Peter’s being “the screaming faggot of State Beach.” Most insidiously, May Lawford responded to her son’s growing apart from her by walking into Louis B. Mayer’s office and telling the prudish studio chief that Peter was a homosexual, a charge that Peter was forced to refute by soliciting the explicit testimony of Lana Turner; the canard drove a permanent wedge between him and his mother.

At MGM, Peter was little more than an English pretty boy, but he had the good fortune of appearing on the scene just as Freddie Bartholomew’s career was in decline. He played light romantic roles well, didn’t shame himself out of the business when he essayed a bit of song and dance, could play gravely enough for small roles in serious drama: a good all-round B-movie lead, or nice support for an A production. He’d never make them forget Olivier, but he was a reliable asset for a studio at something like its height.

Despite his lack of professional distinction, Peter was a highly sought-after invitee, an especially glittering extra in the diadem of Hollywood nightlife; he became known as “America’s guest,” as much for his habit of showing up at every noteworthy party as for his reluctance to pick up a dinner tab.

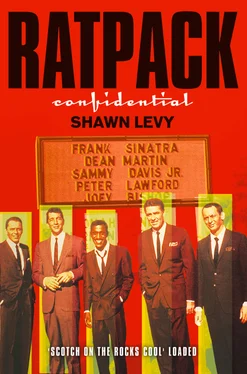

There was, however, another social group with which Peter mingled and to whom he showed an especially generous and loyal side of his nature. Having been introduced to surfing as a young boy in Hawaii, Peter had a genuine love for beach life, and he spent all the time he could at the shore, catching waves, playing volleyball, and steeping himself in the lingo and rituals of beach bums—a cultish society whose vocabulary and attitudes would later be borrowed, in a fashion, by the Rat Pack. May hated the ne’er-do-well manner of this crowd—which, of course, attracted her son to it even more. Moreover, Peter relished mixing his surfing and acting cronies, watching the cultures clash with sophomoric delight.

As he neared his thirties and seemed stuck on a treadmill of light comedy and dull drama at MGM, as his genteel parasitism grew wearying, two life-altering events befell him. At eighty-seven, General Lawford died contentedly in his garden, so deeply rattling Peter that he initially refused to return from Hawaii and endure the funeral. Nine months later, he found himself engaged once again, seriously this time, to Patricia Kennedy, the strong-willed sixth child of Irish-American Croesus and political dynast Joseph P. Kennedy.

Pat Kennedy was not a soft, obliging Hollywood gal. She was not as pretty as Peter’s other fiancées, nor as sensual, but she was sharp-witted and independent and spunky. She didn’t just throw open her legs for him because he was a handsome movie star who talked nice; she challenged his opinions and stood up for her own beliefs in a fashion that must’ve reminded Peter at least a little bit of May. Peter and Pat drew toward one another with surprising ease, not slaving over one another but respectful of their mutual independence. They were in their thirties and set in their ways; their relationship seemed as much one of siblings as of lovers.

Everyone knew what Pat saw in Peter, but many observers, especially Pat’s very jaded father, Joe Kennedy, saw something suspicious in Peter’s commitment to the relationship: Pat, though smart and vivacious, was no beauty, so Peter’s affection tended to give off a mercenary vibe, at least at first blush; moreover, Joe was appalled at Peter’s baroque Hollywood manner—the actor wore red socks to their first meeting—which seemed to lend credibility to the gossip he’d heard about Peter’s catamitic proclivities.

To satisfy himself as to the first matter, he had Peter agree to a prenuptial pact that protected Pat’s fortune (at the crucial moment, though, he forgave Peter from signing it, satisfied at his willingness to do so). As for the other, he importuned upon J. Edgar Hoover to open his infamous store of Official and Confidential files, which revealed that Peter was a well-known patron of Hollywood prostitutes. Rather than blanch at this evidence of Peter’s moral character, lascivious Old Joe, who approved of hearty sexuality, even in potential sons-in-law, was delighted. The courtship climaxed in a lavish April 1954 wedding. Peter Lawford had graduated from waning pretty-boy actor to American royal—a hot number all of a sudden.

Читать дальше