In later years, Sammy looked back on his tender introduction to showbiz as an idyll, but it was a terrifically difficult era. The Chitlin Circuit, as the route of black vaudeville and burlesque houses was known, never paid what the white theaters did; moreover, Sammy broke in when all forms of live entertainment were taking a hit from talking movies, radio, and recorded music. Scuttling back and forth between sporadic, low-paying jobs, Big Sam and Mastin frequently went without food so that their little protégé might not go hungry—and even then his supper might consist of a mustard sandwich and a glass of water. With grim regularity, they all returned to Harlem to sit waiting for new offers of work, which became even less steady with the advent of the Depression.

This was hell for Mastin, by all accounts a decent, intelligent, gifted man who’d risen to a position of respect within the narrow world of black showbiz. Although he never crossed over to broad white appeal, Mastin was a success, able to keep dozens of people on the road with him throughout the twenties. When he had to dissolve his traveling show to a two-man act featuring just himself and Big Sam, he surely felt as though he’d shrunk in the world; trouper that he was, though, he never let on, least of all to Sammy, that there was anything small about the small time.

And Sammy would’ve noticed if he had, because he was watching. He spent his early years studying acts from the wings, then imitating what he’d seen for the backstage entertainment of his makeshift family. He was a natural, and Mastin and Big Sam quickly realized it would give the show a lift if they put the little ham onstage. They slathered him in blackface and sat him in a prima donna’s lap while she sang “Sonny Boy,” the Al Jolson hit; mugging and mimicking during her sober reading of the song, Sammy brought down the house.

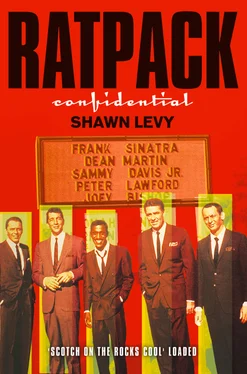

In time, he would master little comic bits, dance steps, vocal impressions, and songs of his own, and his skills grew along with his exposure. From special billing—“Will Mastin’s Gang featuring Little Sammy”—he became a full-fledged part of the act, the Will Mastin Trio, with all three sharing equally in the profits. They were flash dancers: Cat-quick and athletic, they could do time steps together or improvise wild solos, all energy, all arms, legs, and deferential smiles; for six or eight minutes a night, they could wring an audience limp with their sheer gutty bravado.

It was as a member of the trio that Sammy found himself in Detroit in the dog days of 1941, a substitute opening act for the Tommy Dorsey band. As he wandered backstage marveling at the size of Dorsey’s operation, Sammy was offered a handshake by a skinny white guy in his twenties: “Hiya. My name’s Frank. I sing with Dorsey”

“That might sound like nothing much,” Sammy recalled later, “but the average top vocalist in those days wouldn’t give the time of day to a Negro supporting act.” And Frank did more: For the next few nights, until the regular opening act returned, he would sit with Sammy in his dressing room shooting the breeze, talking about the show life. The kid couldn’t believe his luck.

But if meeting Sinatra was a glimpse of a raceless Eden, the next few years were a crushing racist hell. Sammy was drafted into an army that was a cesspool of bigotry. He felt it the moment he arrived in Cheyenne, Wyoming, for basic training.

“Excuse me, buddy,” he asked a white private he came across while trying to find his way around. “Can you tell me where 202 is?”

“Two buildings down. And I’m not your buddy, you black bastard!”

It was a slap in the face, but it was only the beginning. For two years, Sammy was denigrated, demeaned, and, truly, tortured. He was segregated by a corporal who created a no-man’s-land between his bed and those of white soldiers. His expensive chronograph watch (a going-away gift from Mastin and Big Sam) was ground into useless pieces under a bigot’s boot. He was nearly tricked into drinking a bottle of urine offered to him as a conciliatory beer; his tormentors reacted to his refusal to imbibe it by pouring it on him. He was lured to an out-of-the-way building and held against his will while “Coon” and “I’m a Nigger” were inscribed on his face and chest with white paint.

And there were the beatings. “I had been drafted into the army to fight,” he remembered, “and I did.” He was goaded frequently into using his fists as a means of settling the score with the pigs who abused him, breaking his nose twice, scoring his knuckles with cuts.

Only when he was asked by an officer to take part in a show for the troops could he lift his spirit above the dreadful situation. At first, he didn’t want to expose himself on a stage and entertain the very people who’d been mistreating him, but he couldn’t resist the temptation to perform. George M. Cohan Jr. was also stationed in Cheyenne and convinced Sammy to help him create a touring production that would visit a number of military installations. Sammy threw himself into the work with a kind of violence, seeking release, vindication, and even revenge by being the best song-and-dance man anyone had ever seen.

“My talent was the weapon,” he recalled, “the power, the way for me to fight.” For the last eight months of his service time, the show was continually on the road, far from his most virulent antagonists. It kept him sane, maybe even alive.

But when he got out, his eyes having been opened to his situation as a black man with grand aspirations in America, he found himself increasingly crushed by the gap between his ambitions and his opportunities. He was befriended by Mickey Rooney, who, though still one of the hottest stars in Hollywood, was unable to get him movie work. He winced at the ebonic clichés employed by performers on the Chitlin Circuit. In reaction, he adopted a stage manner so patently artificial that he sounded, in his own words, like “a colored Laurence Olivier.” Even the tone-deaf Jerry Lewis was to encourage him to forgo his “with your kind permission we would now like to indulge” routine, but Sammy only did so after, typically, listening for several self-lacerating hours to tape recordings of his own inflated persiflage. And he reacted with despair and self-loathing whenever he was confronted with the insidious—and frequently overt—limits placed upon him in the Jim Crow era.

Nowhere were these barriers more painfully imposed than in Las Vegas, where the Will Mastin Trio debuted in 1944. Vegas was still a cowboy town, “the Mississippi of the West,” as blacks unfortunate enough to live there called it. The black population, whose members swelled the ranks of janitors, porters, and maids at the emerging hotel-casinos on the Los Angeles Highway (which had yet to be christened the Strip), was restricted to living, eating, shopping, and gambling in a downtrodden district known as Westside—a Tobacco Road of unpaved streets bereft of even wooden sidewalks, lined by shacks that lacked fire service, telephones, and, in many cases, electricity and indoor plumbing.

Sammy ought to have been used to segregation. The trio arrived in Vegas not long after a stint in Spokane, where they were forced, for lack of a black rooming house, to sleep in their dressing room. But Vegas galled him more than anything he’d experienced before, in part because of the appalling contrast between the glamour of the Last Frontier hotel and the shack in which he was forced to spend all of his offstage time, and in part because the gaiety and glitz of the casino—which he wasn’t allowed to walk through or even see —had an almost visceral allure for him.

As in the past, the only time he ever felt lifted out of himself and his miserable situation was onstage—“for 20 minutes, twice a night, our skin had no color.” As in the past, he fought off his frustrations and the indignities of racism with ferocious performances—“I was vibrating with energy and I couldn’t wait to get on the stage. I worked with the strength of 10 men.” But never, as he dreamed might happen, did a casino manager or owner grow so enamored of his performance that he broke the color line by offering him a drink and a chance to try his luck at the tables.

Читать дальше