COPYRIGHT COPYRIGHT DEDICATION A NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION AND DATES INTRODUCTION 1. THE SWINDLING MAGICIAN 2. NAPOLEON AND AFTER 3. FLEET AS LIGHTNING: The Career of Ekaterina Sankovskaya 4. IMPERIALISM 5. AFTER THE BOLSHEVIKS 6. CENSORSHIP 7. I, MAYA PLISETSKAYA EPILOGUE PICTURE SECTION NOTES INDEX ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

This 4th Estate paperback edition published in 2017

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by 4th Estate

First published in the United States by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. in 2016

Copyright © 2016 by Simon Morrison

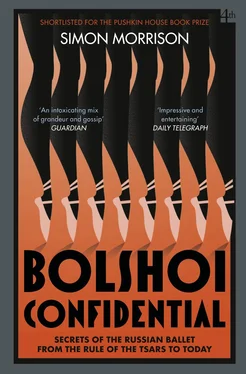

Cover image by Jo Walker

Anna Sobeshchanskaya as Odette; Gorsky’s ‘choreographic photo etudes,’ 1907–09; Simon Virsaladze, Alexander Lavrenyuk, and Plisetskaya, Legend of Love , 1972 courtesy of Bakhrushin Museum. The Bolshoi Theater, May 15, 2015, courtesy of author.

All other images courtesy of Russian State Archive of Literature and Art.

Simon Morrison asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007576630

Ebook Edition © October 2016 ISBN: 9780007576623

Version: 2017-05-31

DEDICATION DEDICATION A NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION AND DATES INTRODUCTION 1. THE SWINDLING MAGICIAN 2. NAPOLEON AND AFTER 3. FLEET AS LIGHTNING: The Career of Ekaterina Sankovskaya 4. IMPERIALISM 5. AFTER THE BOLSHEVIKS 6. CENSORSHIP 7. I, MAYA PLISETSKAYA EPILOGUE PICTURE SECTION NOTES INDEX ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

For Nika, who retired from ballet

before she was five.

• • •

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

A NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION AND DATES

INTRODUCTION

1.THE SWINDLING MAGICIAN

2.NAPOLEON AND AFTER

3.FLEET AS LIGHTNING: The Career of Ekaterina Sankovskaya

4.IMPERIALISM

5.AFTER THE BOLSHEVIKS

6.CENSORSHIP

7.I, MAYA PLISETSKAYA

EPILOGUE

PICTURE SECTION

NOTES

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

A Note on Transliteration and Dates

• • •

THE TRANSLITERATION SYSTEMused in this book is the one devised, phonetically, by Gerald Abraham for the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (1980), with the modifications introduced by Richard Taruskin in Mussorgsky: Eight Essays and an Epilogue (1993). It renders the Russian letter ы as ï and the аи combination in the name Михаил as Mikhaíl. Exceptions to the system concern some commonly accepted spellings of Russian and non-Russian names and places (for example, Alexei rather than Aleksey, Dmitri rather than Dmitriy, Maddox rather than Medoks, St. Petersburg rather than Sankt-Peterburg) and surname suffixes (Verstov sky rather than Verstov skiy ). For ease on the eye, I favored Ekaterina over Yekaterina and Elena over Yelena. In the bibliographic citations, however, the transliteration system is heeded without exception (Dmitriy rather than Dmitri, and so on). Surname suffixes are presented intact, and soft signs preserved as diacritical apostrophes.

RUSSIA RETAINED USEof the Julian calendar from antiquity until January 1, 1918, when the Bolsheviks under Lenin mandated the conversion to the Gregorian calendar of western Europe. Before the reign of Peter the Great (1682–1725), Russians marked the start of the year on September 1 rather than January 1, and numbered years from the date of the creation of the Earth rather than the birth of Christ. Peter the Great reformed the counting of the years but upheld the use of the Julian calendar in deference to the Russian Orthodox Church. So in effect, before the Bolshevik overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II, the Russian calendar was twelve days behind that of the western European calendar. In this book, dates are specified according to the calendar in use in Russia: Julian before 1918 (abbreviated O.S.), Gregorian afterward.

ON THE NIGHTof January 17, 2013, Sergey Filin, artistic director of the Bolshoi Theater Ballet, returned to his apartment near the central ring road in Moscow. He parked his black Mercedes outside the building and trudged through the wet falling snow toward the main entrance. His two boys were asleep inside, but he expected that his wife Mariya, herself a dancer, would be waiting up for him. Before he could tap in the security code to open the metal gate, however, a thickset man strode up behind him and shouted a baleful hello. When Filin turned around, the hooded assailant flung a jar of distilled battery acid into his face, then sped off in a waiting car. Filin dropped to the ground and cried for help, rubbing snow into his face and eyes to stop the burning.

The crime threw into chaos one of Russia’s most illustrious institutions: the Bolshoi Theater, crown jewel during the imperial era, emblem of Soviet power throughout the twentieth century, and showcase for a reborn nation in the twenty-first. Even those performers, greater and lesser, whose careers ended in personal and professional sorrow could justly believe that their lives had been blessed thanks to the stage they had graced. The Bolshoi’s dancers transcended the cracked joints, pulled muscles, and bruised feet that are among the hazards of ballet to exhibit near-perfect poses and unparalleled equipoise. Orphans became angels within the schools that served the theater in the first years of its existence; the Bolshoi then nurtured the great ballet classics of the nineteenth century, and more recently the sheer skill of its dancers has redeemed, at least in part, the ideological dreck of Soviet ballet. The attack on Filin dismantled romantic notions of the art and its artists as ethereal, replacing stories about the breathtaking poetic athleticism on the Bolshoi stage with tales of sex and violence behind the curtain—pulp nonfiction. Crime reporters, political and cultural critics, reviewers, and ballet bloggers alike reminded their readers, however, that the theater has often been in turmoil. Rather than an awful aberration, the attack had precedents of sorts in the Bolshoi’s rich and complicated past. That past is one of remarkable achievements interrupted, and even fueled, by periodic bouts of madness.

Читать дальше