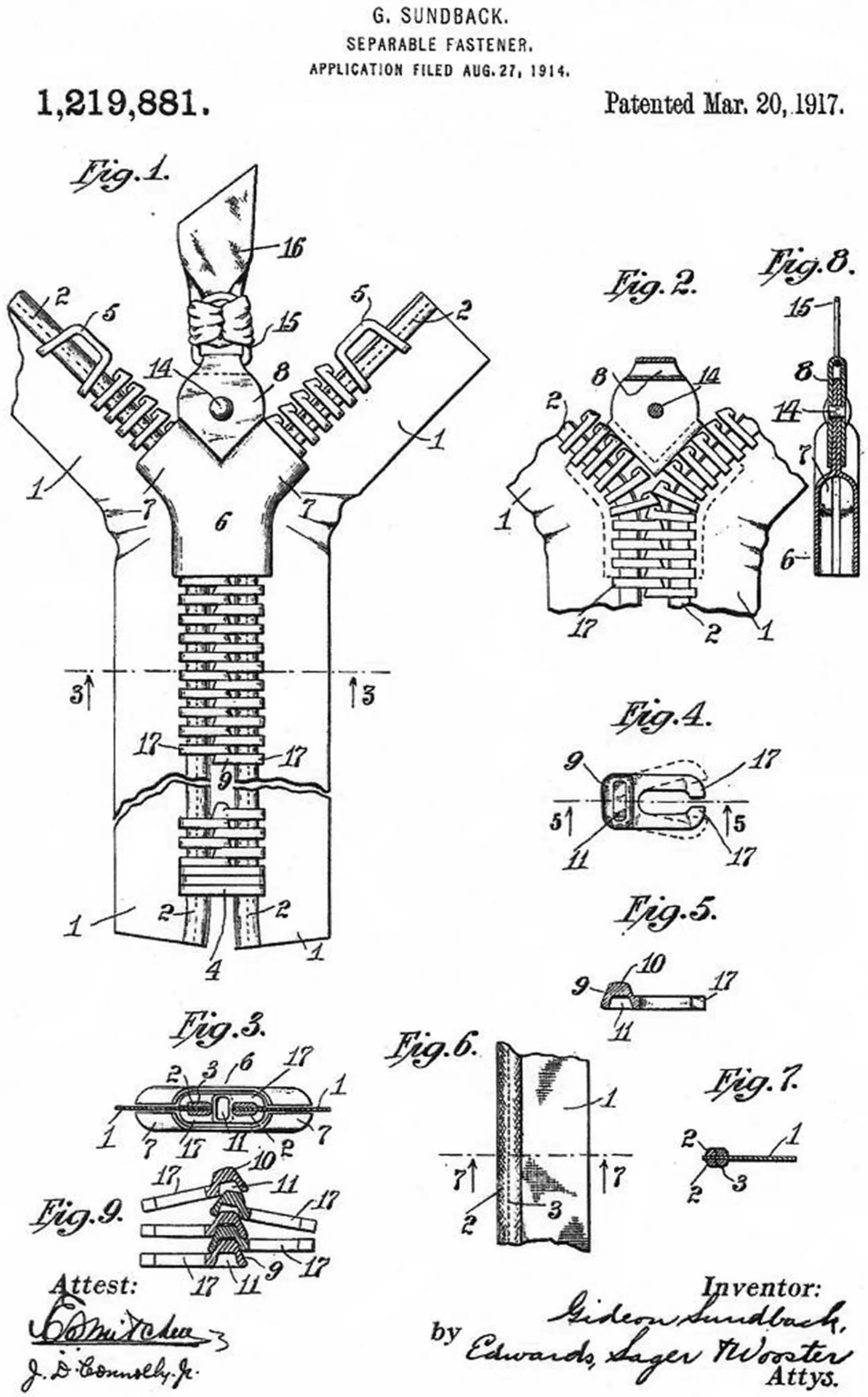

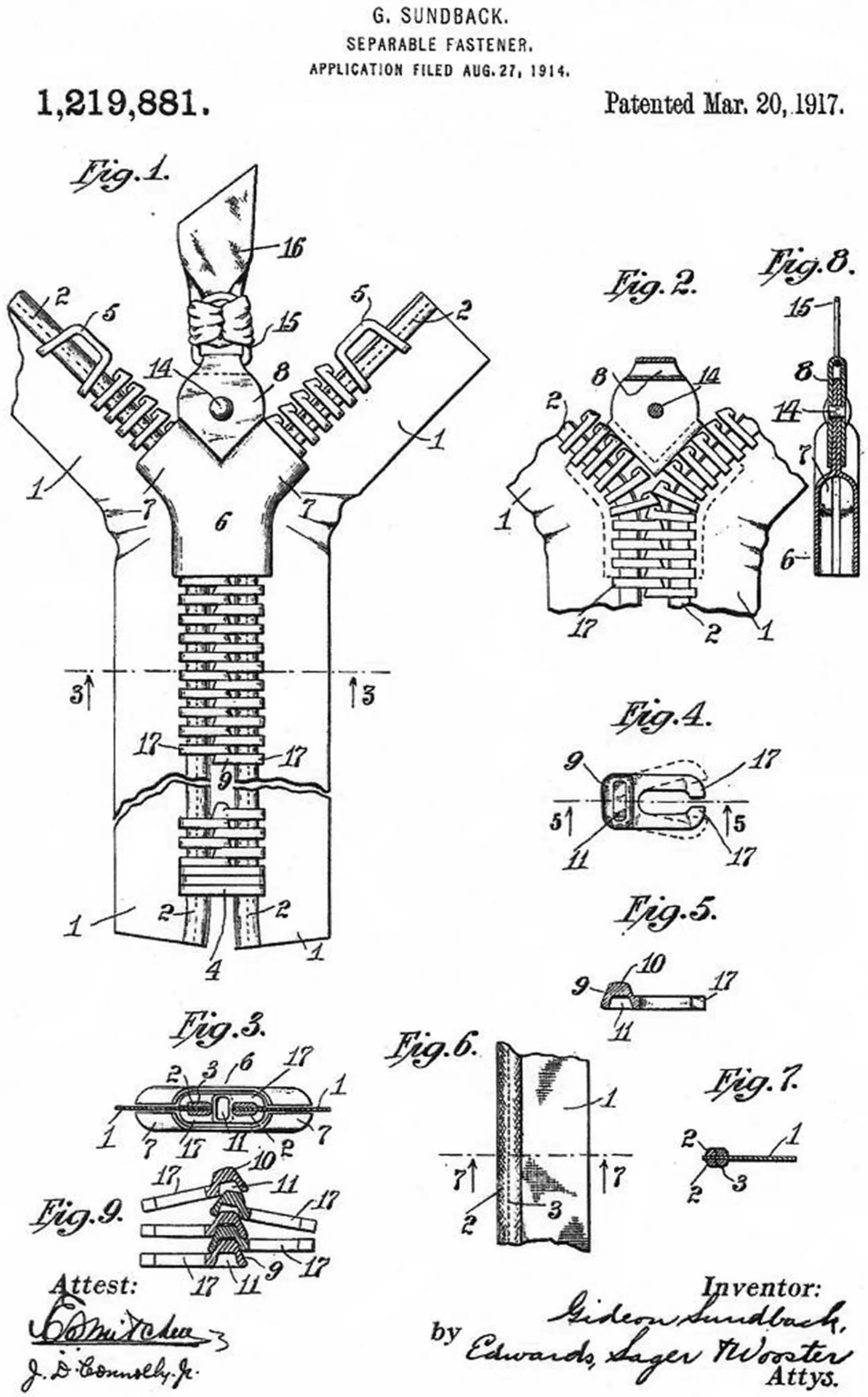

In the 1930s, a sales campaign began for children’s clothing featuring zippers, with the theme that young children would become self‐reliant by allowing them to dress themselves in self‐help clothing. In 1937, French fashion designers raved over the use of zippers in men’s trousers. Esquire magazine at one time stated that the zipper was the newest tailoring idea for men, and a virtue of zipper flies was that they would prevent “the possibility of unintentional and embarrassing disarray.”

A boost for the zipper arrived when zippers could open on both ends, such as on jackets. Thousands of zipper miles are presently produced daily. You may see the letters “YKK” printed on some metal zipper pull‐up tabs. This stands for “Yoshida Kogyo Kabushikikaisha,” a Japanese manufacturer that produces approximately 50% of all zippers sold throughout the world.

4 Introductory Comments on Patentable Subject Matter and Utility

4.1 WHAT CONSTITUTES PATENTABLE SUBJECT MATTER?

4.1.1 Categories of Patentable Subject Matter

The first threshold that must be reached in determining whether your invention constitutes patentable subject matter is to establish that the invention itself is in the form of an embodiment, such as a prototype, or has been described or illustrated in terms sufficiently tangible and concrete, and not merely conceptual, to qualify for patent protection. Once this tangible or illustrated embodiment of your invention has been created, it must be determined whether the invention falls within one of the statutory classes of patentable inventions covered by 35 U.S.C. Section 101, which means that the invention must be a process, a machine, an article of manufacture, or a composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof. At this point, it must also be determined whether an article patent, method (process) patent, design patent, or a combination of any of these would best serve the interests of protecting the technology embedded in the invention. More recently, algorithms embodied in software and tied to a machine, biotech strains, and business methods are patentable subject matter, but only under certain conditions. These three types of inventions and the present rules regarding their patent eligibility will be discussed in the ensuing chapters owing to the somewhat complex nature of the legal analyses applicable to these categories of inventions.

More specifically, a process or method may involve treating a material to produce a particular result or product, or may involve manipulating tangible matter to produce a desired end result. One example would be a process to temper glass to make it break resistant. Processes can also comprise a new use for a known composition, such as a new use for a known chemical compound.

A machine is a device that performs a useful operation, usually having mechanical or electrical components, such as, for example, springs, hinges, transistors, resistors, sensors, controls, etc. A composition of matter is a combination of two or more substances, and includes chemical elements or compositions, such as a soft drink formulation or a drug compound.

A manufacture is a catch‐all category for the remaining statutory subject matter which comprises anything not a process, machine, or composition of matter. A manufacture may be a human‐made genetically engineered bacterium, for example, which is capable of breaking down crude oil. Included among “things” that are not patentable subject matter are purely mental processes, naturally occurring articles, scientific principles, and abstract ideas.

4.1.2 The Invention Must Be Useful and Work for Its Intended Purpose

To be patentable, an invention must be shown to work for its intended purpose. Under the Constitutional mandate of Article 1, Section 8, patents can only be granted for advances in the “useful” arts. A patent cannot be granted for an inoperative device or method, and is subject to post‐grant cancellation if the covered device is proven to be inoperative. This is the reason why patents on perpetual motion machines are not granted—they do not work. See Section 4.2ahead.

4.1.3 The Invention Must Be Novel Compared to the Prior Art

Throughout the globe, patents are granted only on inventions that are novel, as measured against the vast body of relevant prior art existing in the world. For example, a public disclosure, use, or sale of, or an offer to sell, a product anywhere in the world by you or someone else, which product embodies your “new” technology prior to the home country filing date of your patent application, is considered prior art in many industrialized countries and would bar you from obtaining a patent. In the United States, an inventor has a 1‐year grace period to file a patent application after a public disclosure of the invention. These and other limitations on novelty will be covered in more detail in Chapter 5.

4.1.4 The Invention Must Be Non‐Obvious as Compared to the Prior Art

The U.S. patent statutes, and most patent statutes throughout the world, state that, even though there are differences between the invention attempted to be patented and the prior art, if those differences would be mere obvious manifestations of the technology by one skilled in the art to which the subject matter of the patent relates, patent protection may not be obtained. The determination of obviousness is rather difficult to those uninitiated in dealing with patents, and Chapter 6is dedicated solely to the history, and technical and legal determinations, involved in showing how the standard of unobviousness plays an important role in the granting and enforcement of patents.

4.1.5 The True Inventors Must Be Named

In the United States, patent applications must be originally filed setting forth the names of the inventor, or inventors if there are more than one, or in the name of a business entity to which the inventor or inventors are obligated to assign their invention, possibly pursuant to an employment contract or other agreement. The application, upon filing, can be immediately filed in the name of the company for whom the inventors work. Also, if the inventors have decided prior to filing the application that they desire to assign the rights either equitably among each inventor, or to other individuals, the application may be filed in the name of each inventor or such other individuals or company. However, it is important to know that, in the United States, the true inventors must initially be identified in a patent application data sheet that accompanies filing of the patent application. These inventors must be the true inventors of the subject matter claimed to be novel and non‐obvious in the patent application. A signed assignment document may be filed for recording in the USPTO along with the initial patent application, or later, in which document the inventors assign their rights over to their employers or others.

Regardless of assignment, it is imperative in the United States that the actual inventor or inventors be named in the application documents. The patent laws do not allow those to be named as inventors who did not contribute to the conception or reduction practice of the invention. In several instances during my years of practice, politics within a business environment have resulted in inventors being named who had nothing to do with the actual conception or reduction to practice of the invention. This should be avoided. After the patent issues, and the owner attempts to enforce the patent against an infringer, the acts of invention by the named inventors will be part of the discovery and trial testimony in the case. If it is ultimately determined that the individuals who are named are not the inventors, the patent’s validity and/or enforceability could be jeopardized. Therefore, when working with a patent attorney, the inventors must ensure that all of the proper inventors be named, and also be sure that those who are not inventors do not appear on the application as inventors.

Читать дальше