3.7 THE U.S. GOVERNMENT’S RIGHT TO PRACTICE YOUR PATENTED INVENTION

During World War I, the U.S. government mobilized the nation’s industries to provide munitions and other materials to support the war effort. This program ran into several barriers when patent owners filed patent infringement lawsuits against government contractors, and obtained injunctions stopping the production of needed weaponry, among other military necessities. To correct this situation, the Congress, circa 1918, passed a law that is now codified at 28 U.S.C. §1498. This law provides that, whenever a manufacturer is using or manufacturing an invention described in a U.S. patent for the government and with the authorization and consent of the government, the patent owner cannot bring a patent infringement suit against the infringing user or manufacturer. The patent owner’s only remedy is to file a patent infringement action against the government in the Court of Federal Claims, and the patent owner can only recover “reasonable and entire compensation for such use and manufacture” (28 U.S.C. §1498(a)). The patent owner cannot obtain an injunction stopping the use or production of the patented invention when the government is the ultimate customer.

Under this law, which is still in effect today, the government, by authorizing and consenting to have a patented process used, or a product manufactured, on its behalf, is effectively taking a license under the patent under the powers of eminent domain, whether or not the patent owner wants to grant the government a license. This procedure is akin to the government’s ability to condemn and take private property to construct a highway, for example. When such “taking” occurs, the one whose property, or patent right, has been taken is entitled to be reasonably and entirely compensated, with money, for such taking.

If you discover that the U.S. government has awarded a contract to a competitor who underbid you, and you hold a patent on the subject of the contract, you cannot sue your competitor for patent infringement. You must file your lawsuit against the government in the Court of Federal Claims, and the government lawyers of the U.S. Department of Justice will respond to your lawsuit, usually raising defenses of non‐infringement, patent invalidity, unenforceability of the patent, plus any other of the many defenses to patent infringement that are available. If your competitor, who is the selected government contractor, has agreed in the contract to indemnify or hold the government harmless from patent infringement, the Justice Department attorneys may be accompanied by your competitor’s attorneys in defending against your lawsuit. At the end of the lawsuit, if you prevail, you are awarded your “reasonable and entire compensation” as determined by the Court, which usually is based on a reasonable royalty payment for the infringing sales. However, you will not be awarded an injunction stopping the government from obtaining infringing products from your competitor.

If you discover that the U.S. government has awarded your competitor a contract for the use or manufacture of an invention on which you hold a U.S. patent, my advice is that you contact your patent professional to make a determination regarding the viability of asserting your patent against the government. Remember that, since the U.S. government can obtain a license under any U.S. patent, the contract award can be made to the lowest bidder, regardless of who owns the patent on the subject invention.

Additionally, the same or similar provisions apply to the U.S. government taking a copyrighted work (28 U.S.C. §1498(b)), a patented plant variety (28 U.S.C. §1498(d)), or a mask work or vessel hull design (28 U.S.C. §1498(e)).

INVENTORS AND INVENTIONS

George Westinghouse

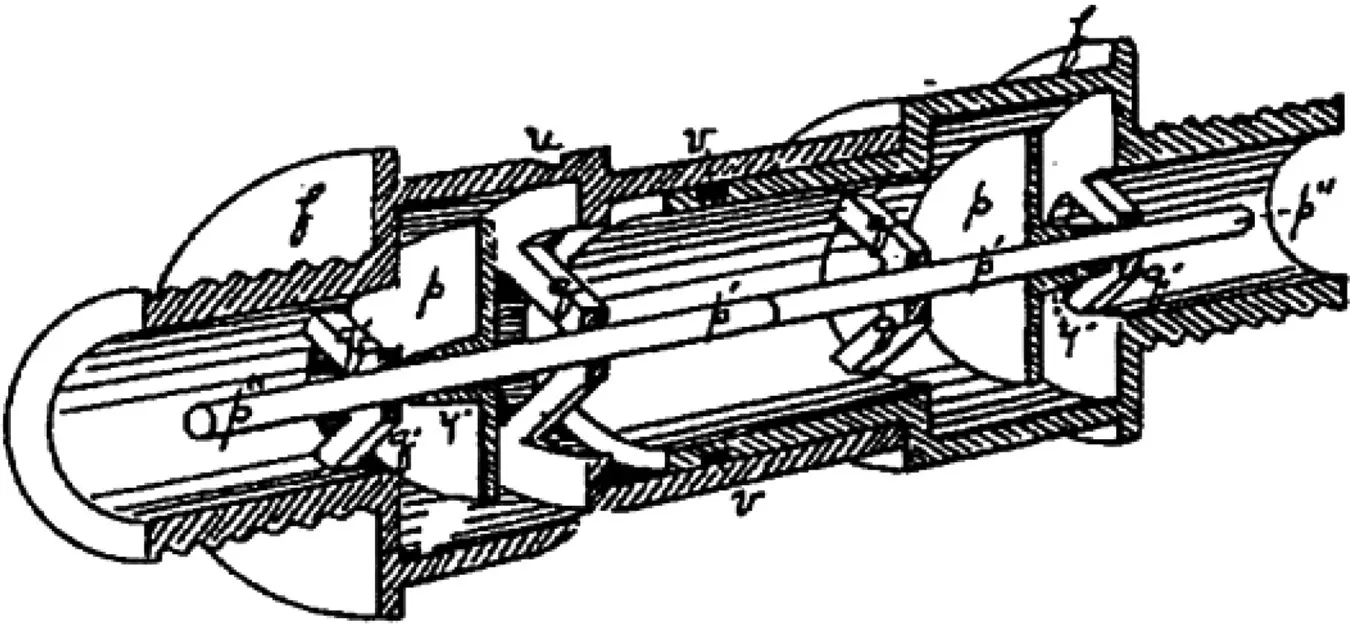

STEAM‐POWER BRAKE DEVICES AND ALTERNATING CURRENT

George Westinghouse is considered by some as one of the most productive inventors of his era, who helped perpetuate the Industrial Revolution through his ambition to resolve technical, commercial, and social obstacles. For example, in 1871, his employees were given a half‐day off on Saturday, the initial step toward the five‐day work week. He created an employee pension fund in 1908, and his workers were given paid vacations in 1913. The first radio station in the world was Westinghouse KDKA in Pittsburgh.

George Westinghouse was born in Central Bridge, New York, on October 6, 1846. He worked in his father’s farm machinery shop in Schenectady, New York, until the age of 15, when he joined the Union Army as a cavalry scout, and then the Union Navy as a naval engineer where he served throughout the Civil War. He briefly attended Union College, and, upon returning to his father’s shop in 1865, he developed and patented a rotary steam engine, a device for replacing derailed freight cars, and a railroad frog.

In 1866, after the war was over, Westinghouse, while working for his father, was a passenger in a train that stopped suddenly to avoid colliding with a wrecked train ahead. He got out, looked over the site, talked to the trainmen, and determined that there must be a better way to brake a heavy train. At that time, the railroads were heavily prone to accidents because each railroad car had its own brakes that were applied separately and manually by brakemen, leaping from car to car upon a signal from the engineer. The danger inherent in this system is obvious.

Meanwhile, in 1867, Westinghouse married Margaret Erskine Walker and moved to Pittsburgh, where he had met others who shared his interest in inventing and manufacturing products for the railroad industry. Westinghouse continued to seek a solution to the train braking problem. He first considered using a chain to couple all of the train’s brake controls, but this did not work. His next idea of using the steam generated by the locomotive to operate steam brakes on each car became impractical when the steam condensed to water and froze in cold weather before reaching the brake systems.

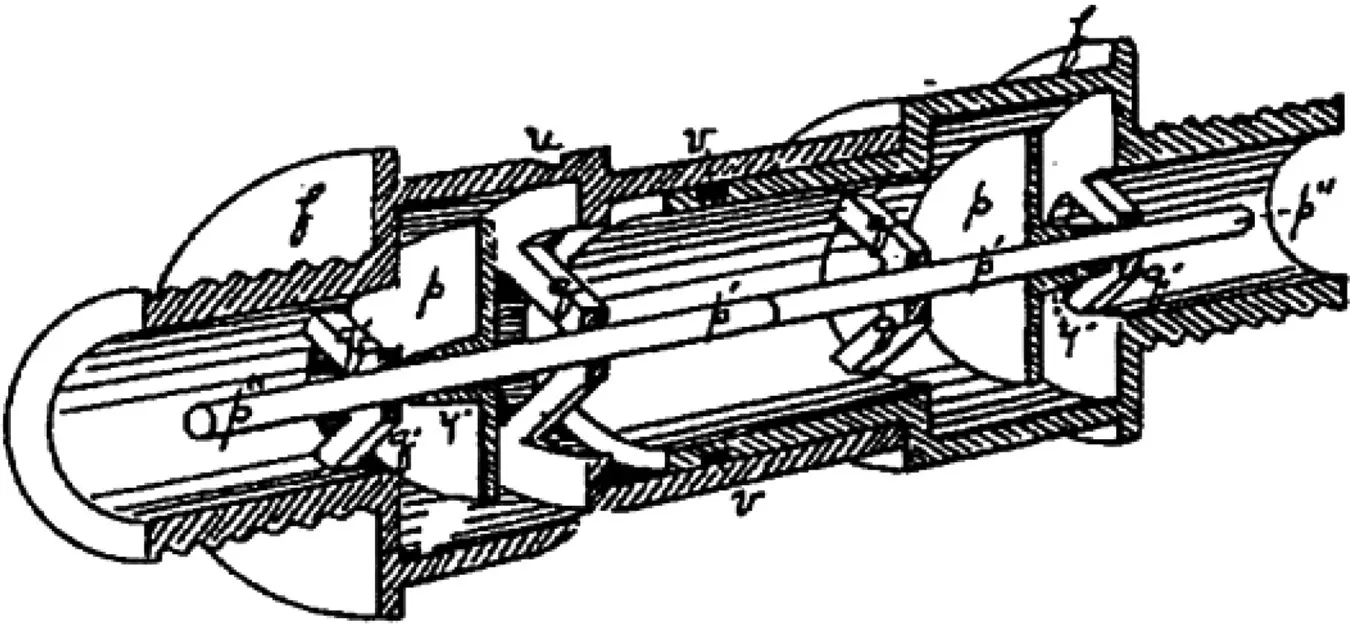

He then learned that engineers drilling dynamite holes in an Alpine tunnel had used a steam engine to produce compressed air that was piped 3000 feet into the tunnel to run the air drills. He applied this technology to an air brake system for trains, and obtained a patent for his air brake on April 13, 1869.

Westinghouse wanted to install a test air brake system on a full‐sized steam‐driven train and approached Cornelius Vanderbilt, president of New York Central Railroad, with a request to “borrow” a locomotive and several cars. When Westinghouse told Vanderbilt that he wanted to stop a train with just air, Vanderbilt had Westinghouse removed from his office.

In 1869, however, Westinghouse convinced Panhandle Railroad to provide him with a locomotive and four cars, on which he installed his air brake system. A test was arranged over the Pittsburgh–Steubenville stretch of Panhandle’s right of way. Panhandle officials and Westinghouse boarded the train, and it started out. At the first and second stations, the train stopped as promised. Before reaching the third station, the engineer saw a horse and carriage stuck at a crossing. The brakes were applied by the engineer hard and fast. The train came to a screeching halt, with most passengers being hurled to the floor. This convinced the Panhandle officials, and Westinghouse, that the engineer‐operated air brake was a vast improvement over the prior manual braking system.

As Westinghouse Air Brake Company, which was organized in July 1869, began to receive orders, Westinghouse built his first factory in Pittsburgh. His brake system gave railroad passengers greater confidence in the safety of their ride, and provided increased efficiency to the owners of the railroads. The Railroad Safety Appliance Act of 1893 made air brakes required equipment on all U.S. trains. The use of air brakes also took hold in Europe, and is today the industry standard.

Читать дальше