To determine the identity of actual inventors on a project that involves several people, I have applied a simple test, which you may also find useful. The addition of technical features to an invention usually does not qualify as contributing to the “invention.” Thus, one who can take a sketch appearing on a piece of paper, and create a workable and valuable product, composition, or other item from the sketch, is normally not named as an inventor. By contrast, an inventor starts with a blank piece of paper and places the sketch on the sheet, which the technician eventually works from. Therefore, in determining who are to be named as inventors in a patent application, it is important to determine who started with the blank sheet of paper, and who acted only in a purely technical capacity and carried out the invention that was actually conceived and reduced to practice by others. In complying with this requirement of the patent law, management should understand that there is no room for politics in the naming of inventors in patent applications.

4.1.6 Brief Commentary on Notable Recent Developments Attempting to Determine Patentable Subject Matter

Several years ago, upon the development of mathematical algorithms for use in computer software, the USPTO refused to grant patent applications on such algorithms, since they were considered to be merely abstract mathematical expressions that existed before. However, as protection for such embedded software became important to business and society, the interpretations of Patent Laws were changed by the courts and the USPTO to include some such algorithms, and the machines that use these algorithms, within the scope of patentable subject matter under certain conditions. Due to the complexity of this issue, Chapter 13explains the present status of the patentability of computer‐related inventions in deeper detail.

Additionally, courts have previously held that living organisms could not be the subject of a patent. However, at present, modified living organisms that are the product of genetic engineering, e.g., human intervention, can be patented, except that people cannot be patented. The products of genetic engineering that are patentable must satisfy all the other conditions for patentability, including usefulness, novelty, and non‐obviousness. Two examples are: the Harvard Mouse, which has been genetically engineered to be more susceptible to certain strains of cancer for purposes of medical research (see U.S. Patent No. 4,736,866); and, second, certain genetically modified organisms which can absorb oil to clean up oil spills that occur when a tanker or pipeline accidentally splits open (see U.S. Patent No. 4,259,444).

Today, the whole subject of genetics falls within the scope of patentable subject matter, and discussions are continually ongoing about the patentability of the results of the Genome Project, which was recently completed. It is my prediction that, in the future, additional patent laws or court decisions will be required to determine which newly developed subject matter may be patented, and which may be available for public use without restraint, as medical procedures are today. The subject matter of biotechnology patents is discussed in detail in Chapter 14.

Prior to 1998, methods of doing business did not fall within any of the categories of patentable subject matter. However, the State Street decision in 1998 ( State Street Bank & Trust v. Signature Financial Group , 149 F.3d 1368 (Fed.Cir. 1998)), by the U.S. Court of Appeals of the Federal Court, held that methods of doing business, whether or not implemented using a computer or software, may also be patented, provided all of the other conditions for patentability are met. One such example of a patent that embodies a business method and which has been litigated in court is a patent covering the method of ordering a product online using a single click of the mouse rather than a double click. The patentability of business methods is discussed in Chapter 15.

The law relating to patentability of inventions in each of the three genres—computer‐related inventions, life science inventions, and business methods subject matter—has been vacillating sinusoidally recently. Therefore, you and your patent professional may find it worthwhile to file a patent application covering an invention that does not, or may only marginally, meet the current criteria for patentable subject matter, with an eye toward the future that your patent claims may be found to cover a new, not‐yet‐determined category of patentable subject matter. As of this writing, certain stakeholders in the U.S. patent system, such as the American Bar Association Intellectual Property Law Section and the American Intellectual Property Law Association, among others, have proposed specific legislation to Congress to clarify what is and is not patent eligible in these three areas. Your patent professional will keep you updated as to any relevant changes enacted by Congress.

4.2 UTILITY — THE INVENTION MUST BE USEFUL

As briefly touched upon previously, under the Constitutional mandate of Article 1, Section 8, patents can only be granted for advances in the “useful” arts. Following this directive, the USPTO and the courts have determined that a patent cannot be granted for an inoperative device or method, and that a patent is even subject to post‐grant cancellation if the covered device is proven to be inoperative.

Also required is that the disclosure in the patent application specification must define an invention and a device that will work for its intended purpose. If the device will not work for the purpose set forth in the specification, the patent, if granted, will become unenforceable and invalid.

The requirement of usefulness also holds that a patent cannot be granted to inventions that have not been developed to the point where a working embodiment can be disclosed in the patent application. This requirement that the invention must be useful is especially significant for new chemical compounds (including pharmaceuticals), because there may be no known use for a new compound. Often, much work must be conducted to experimentally verify the utility of a new compound before a patent application can be filed.

Upon development of any invention, the inventors should ask themselves the question: “What is my idea useful for, and why?” Once this question has been answered, the patent application can be drafted around it, showing that the invention will solve problems in the area in which your idea has been determined by you to be useful.

By way of anecdotal information, many years ago when I was a patent examiner, some of the other examiners in the chemical arts, over lunch, would tell stories about patent applications that were filed on chemical compounds, and that the usefulness for these chemical compounds was described as “for filling sandbags.” These were patent applications that were filed before the applicant corporation really knew what the chemical could be useful for. Today, the requirement is that the invention must have some stated use before the patent application is filed. I do not think filling sandbags today will carry much weight!

INVENTORS AND INVENTIONS

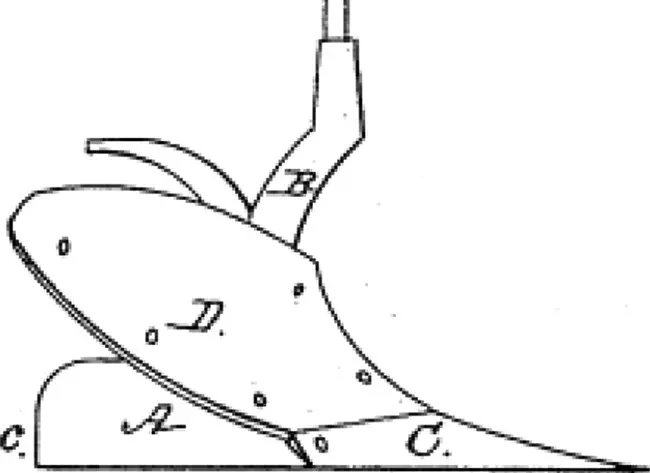

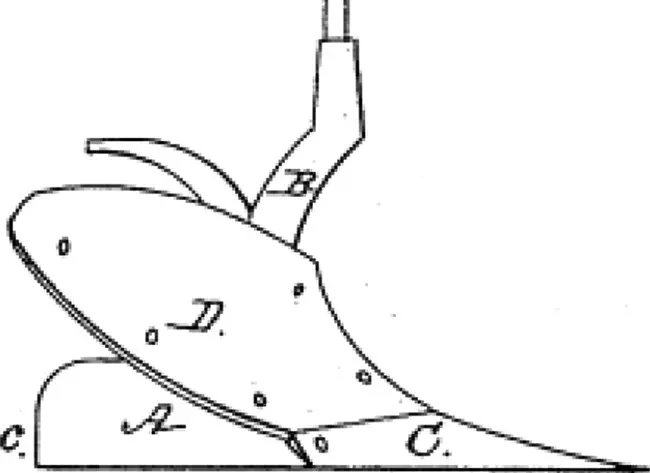

John Deere

HORSE‐DRAWN PLOW

If you have ever been to the country, you have undoubtedly either seen a hat with his name on it or been stuck driving behind one of the behemoth tractors named after him. John Deere is his name‚ and the self‐polishing cast steel plow is his invention.

John Deere was born in Rutland, Vermont‚ on February 7, 1804. He lived in Middlebury, Vermont‚ for a good portion of his life. In 1825, after serving a four‐year apprenticeship, Deere started working as a blacksmith, producing hay forks and shovels, among other implements. He was so good that he soon gained significant fame in the area for his careful workmanship and ingenuity. During the Great Depression of the 1830s, things were not good for Deere or the people of Vermont. Many people decided to move out west, and they sent back stories of “golden opportunities.” After hearing these stories, Deere decided to abandon his business in Vermont and he moved to Grand Detour, Illinois, which was settled by other natives of Vermont. He brought with him a small amount of cash and his tools, which was fortunate because the town needed a blacksmith. Two days after his arrival he had already set up a shop, built a forge, and was busy working. His family then followed him to Grand Detour.

Читать дальше