Interaction between APCs and T Cells: The T-Cell-Dependent Response

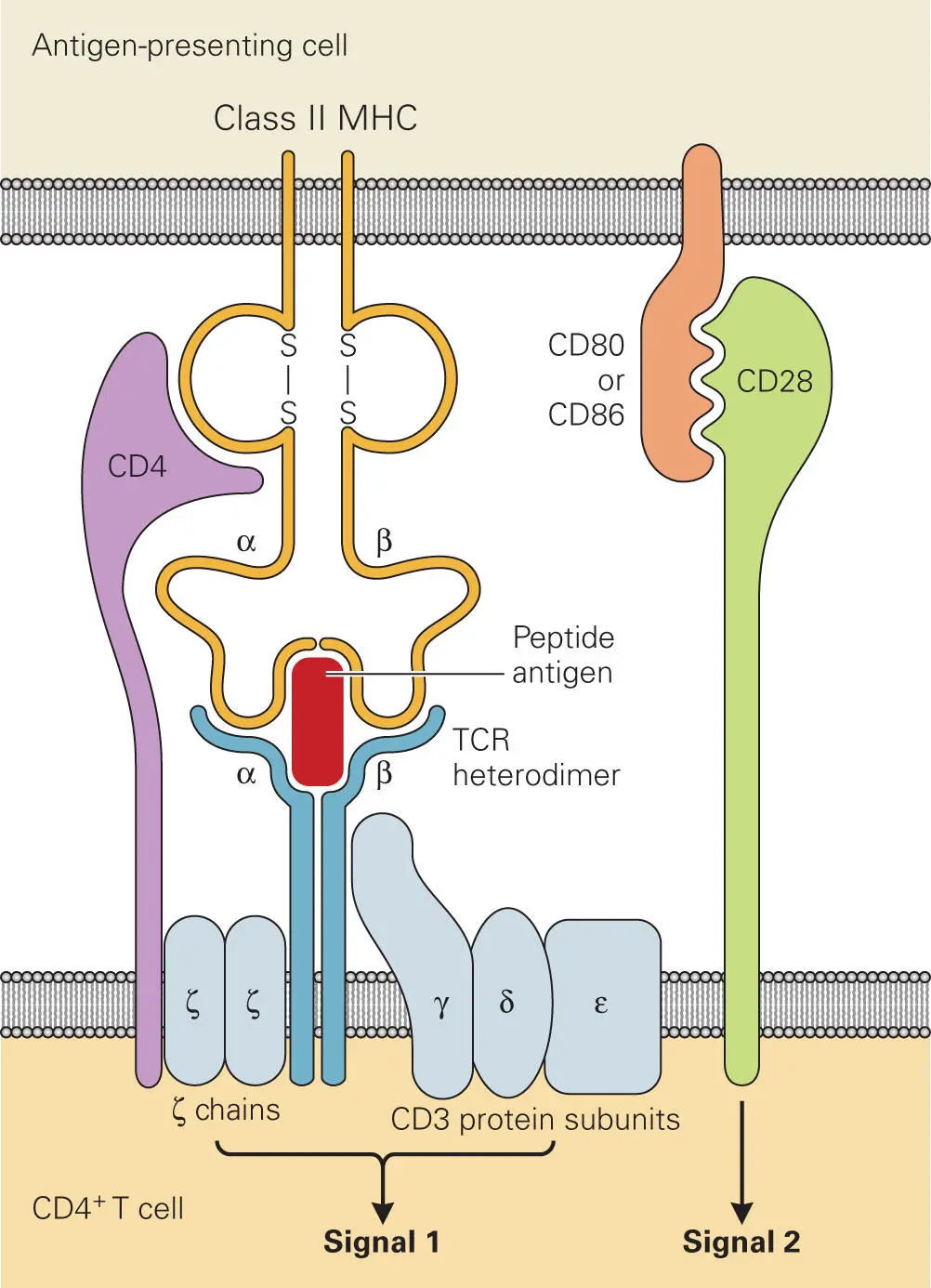

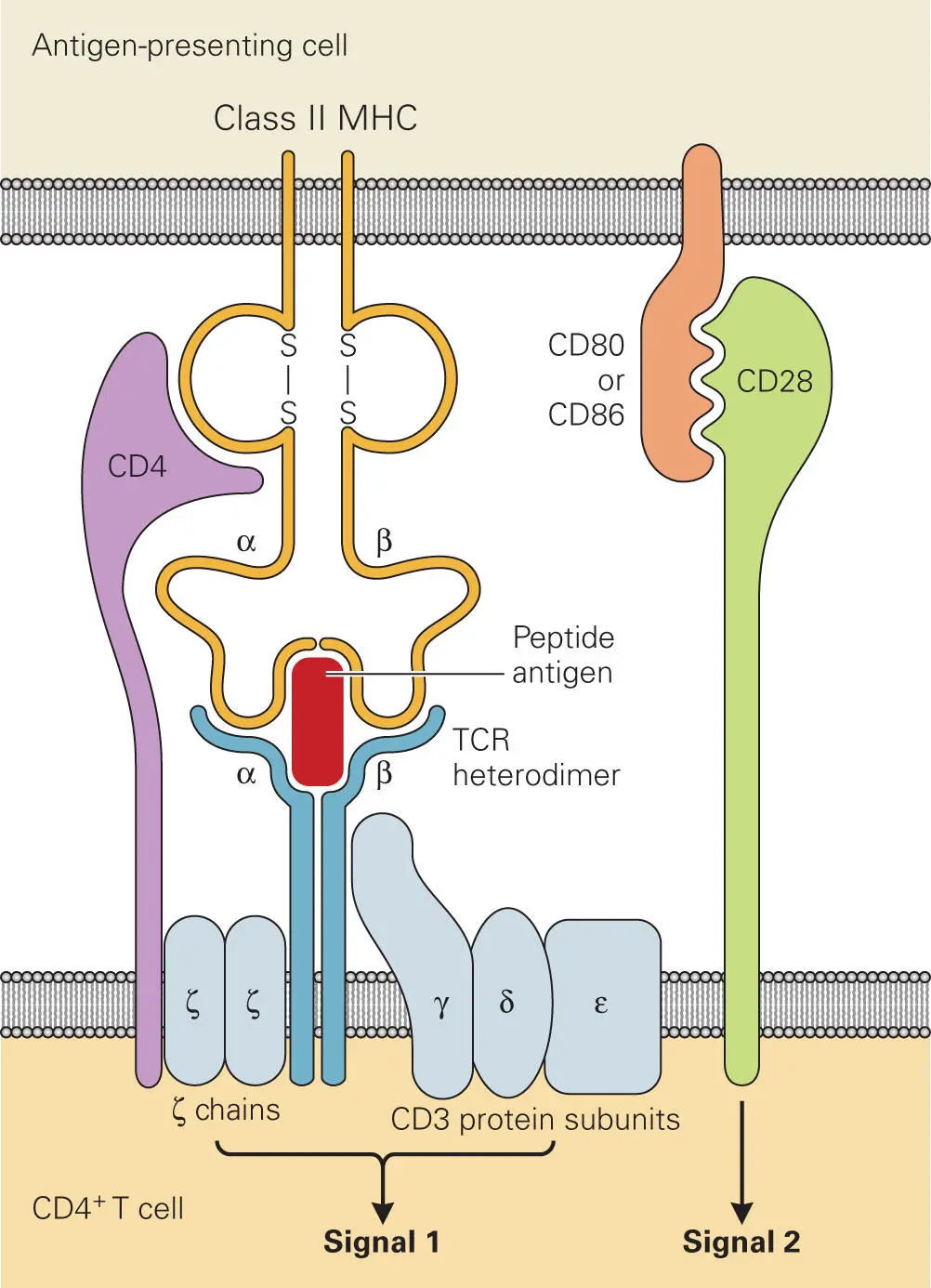

When an APC displays a particular MHC I-epitope or MHC II-epitope complex on its surface, only a small number of the vast pool of available immature precursor T cells will have a TCR capable of recognizing that particular MHC-epitope combination and stimulating the signals needed to induce proliferation and production of cytokines ( Figure 4-8). All T cells express CD3 complexes (comprised of γ, δ, and ε chains) and TCR complexes (comprised of α, β, and two ζ chains). The CD3 and ζ chains are invariant, but the large repertoire of TCRs with surface receptors that recognize a wide variety of different MHC-bound epitopes is generated through variation of the αβ chains, which undergo V(D)J recombination during T cell development in the thymus (analogous to the process mentioned earlier that leads to antibody diversity).

Figure 4-8. The T cell receptor (TCR) complex. Shown is a schematic illustration of the complex formed between the epitope-MHC II complex on the APC and the CD3-TCR complex on the CD4+ Th cell. Note: Similar complex formation occurs for MHC I recognition by CD3-CD8+ T cells. CD4 and CD8 are expressed on two different types of αβ T cells, where CD4 recognizes MHC II complexes and CD8 recognizes MHC I complexes on APCs. Activation of the T cells requires stimulation by two signals: signal 1 occurs through specific interaction of the epitope-MHC II with the CD4-TCR and CD3 complexes and signal 2 occurs upon costimulation through the CD28 binding to CD80 or CD86 on the APC.

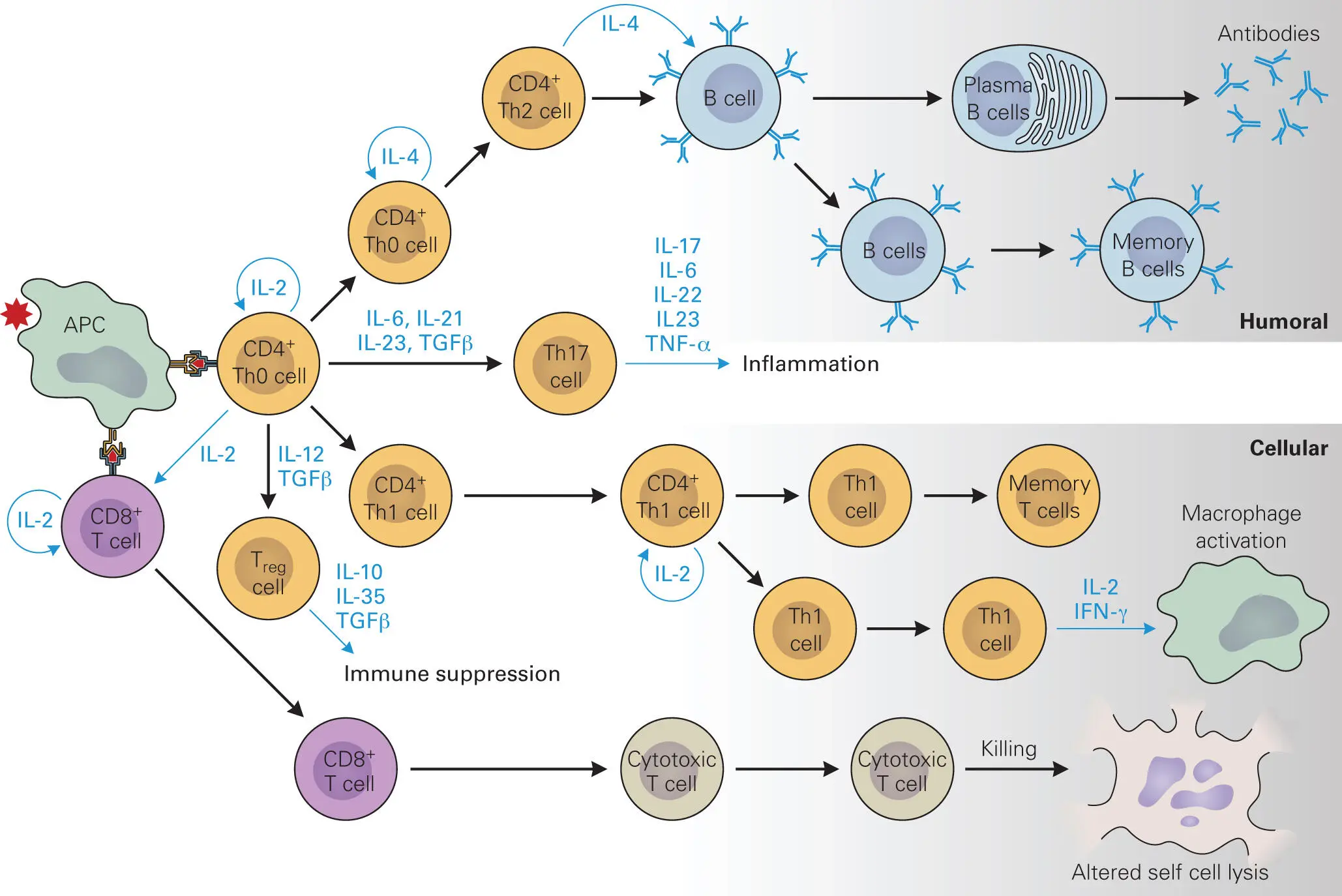

Antigen presentation and binding to the TCR stimulates the T cell to become either a CTL or a T helper (Th) cell ( Figure 4-9). Display of intracellularly derived peptide epitopes on MHC I allows the APC to activate and stimulate the proliferation of CTLs. CTLs are distinguished by the presence of CD8 molecules on their surfaces (hence the name CD8+ cytotoxic T cells). The CD8 molecules, along with the T cell receptor (TCR), are responsible for recognizing only antigen-bound MHC I complexes on the APC. CD8 binds to MHC I and stabilizes the interaction between epitope-bound MHC I and the TCR. CTLs are particularly well equipped to recognize infected cells because virtually all cells of the body produce MHC I. If a cell is infected, it displays epitopes from the invading microbe on its surface. Binding of a CTL to the surface of an infected cell causes the CTL to release cytolytic or apoptotic proteins that can kill the infected cell, as described earlier (see Figure 4-5). In addition, as described in chapter 3, NK cells also use the amount of MHC I on cell surfaces as an indicator of cell health, because infected cells generally express less MHC I than normal cells.

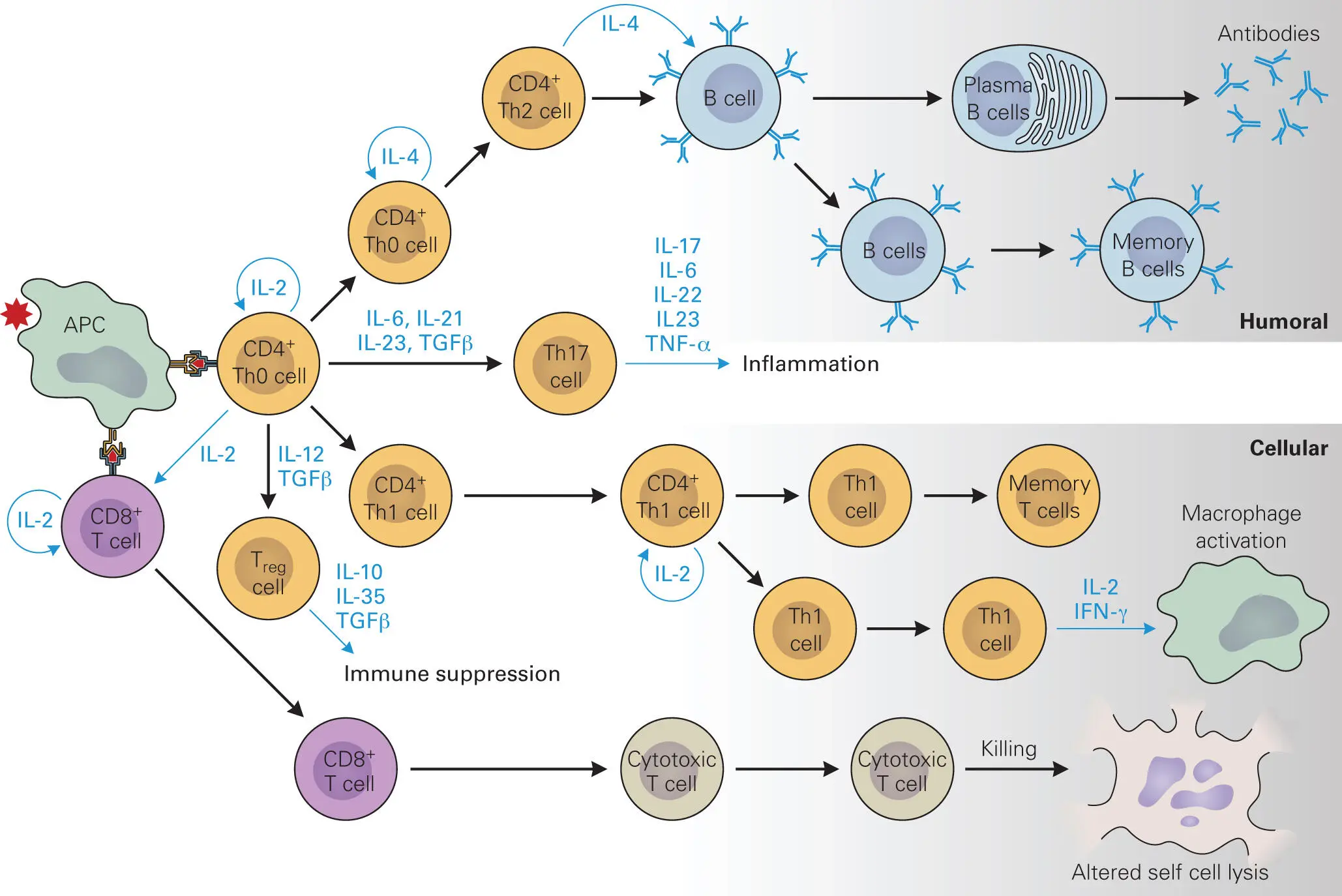

Figure 4-9. T-cell-mediated immunity and memory. Characteristics of the antigen (Ag) determine whether the antigen is presented via APCs through MHC I complexes or through MHC II complexes. Ag-MHCI complexes bind to TCRs on CD8+ T cells that trigger the CTL response. Ag-MHC II complexes that bind to TCRs on CD4+ Th0 cells trigger IL-2 cytokine production and maturation into CD4+ Th1 cells, leading to cellular immunity or, in the subsequent presence of IL-4 into CD4+ Th2 cells, leading to stimulation of the antibody-producing B cell response. Cytokines and the presence of Th17 cells help direct the type of cell-mediated immunity and memory that occurs. Treg cells help control the immune response, especially once the pathogen has been cleared from the system.

In contrast, if an epitope is presented by the APC in complex with MHC II rather than MHC I, a different class of T cells, T helper (Th) cells, is stimulated. Complex formation between TCRs and coreceptor CD4 molecules on the surface of precursor Th cells (called CD4+ Th0 cells) with epitope-bound MHC II molecules on the surface of APCs leads to production of IL-2 and then IL-4 by the Th0 cell and proliferation and maturation. Proliferating Th cells come in two types: Th1 and Th2 cells. These Th cells influence a variety of immune responses through release of cytokines, and how they do this is a very active area of research in the field of immunology.

Other proteins on the surface of the APC and the Th cell, called costimulatory molecules (e.g., CD54, CD11a/CD18, CD58, CD2), must also interact to make the binding between the APC and the Th cell tight enough to stimulate the APC to release cytokines that stimulate the Th cell to proliferate and become activated. Th1 cells are stimulated to proliferate by IL-12 and IL-2 released by APCs, which causes the Th1 cells to release more IL-2 (positive feedback), IFN-γ, and TGF-β. Recognition of MHC II-epitope by CD4+ Th1 cells also stimulates the production and release of IL-2 and IFN-γ, which in turn activate macrophages. Th1-cell-mediated responses lead to cellular immunity, which is most effective against intracellular pathogens. The necessity for contacts between different surface proteins of the APC and the Th cell helps ensure that only specific binding of an MHC-epitope complex to its cognate TCR will result in Th cell activation.

Th2 cells are stimulated to proliferate by IL-4, which causes the cells to release more IL-4 (positive feedback), as well as other cytokines (IL-5, IL-9, IL-10, and IL-13), which modulate other immune cells. MHC II-epitope stimulation of CD4+ Th2 cells stimulates naïve B cells to proliferate into B cells and mature into antibody-producing plasma cells (i.e., humoral immunity) and memory B cells. IL-4 also stimulates B cells to produce IgE antibodies, which in turn stimulate mast cells to release their cytokines (histamine, serotonin, and leukotrienes). The Th2 response is most effective against extracellular pathogens.

Once activated, T cells begin to proliferate, with most of the resulting effector Th cells becoming involved in combating the invading microbes. A few of the T cells, however, become quiescent memory T cells. Memory T cells persist for long periods in the body. They are generally present in higher numbers than naïve T cells with the same TCR, and they are more easily stimulated to proliferate and produce stronger cytokine responses when they encounter their specific epitopes on APCs during subsequent infections. Memory T cells thus allow the body to respond to a second encounter with a particular microbial invader much faster and more strongly than it did after the initial encounter.

Some bacteria and viruses produce proteins called superantigens that interfere with this highly specific progression of events in an interesting way that will be described in greater detail in chapter 12. Superantigens force a close association between APCs and T cells through abnormal association of MHC and the TCRs without a matched antigen. Normally, only a small fraction of T cells will interact with APCs presenting antigens on their surface. Superantigens, on the other hand, can cause up to 20% of T cells to participate in such interactions. As the cytokine signaling begins, cytokines are produced at higher levels than normal and this overreaction can trigger shock. The term “septic shock” is sometimes used to describe this phenomenon; however, as described in chapter 3, LPS or other bacterial surface components usually initiate what is considered septic shock. The term “T-cell-mediated shock” or “toxic shock” might be more appropriate to describe the shock initiated by superantigens, to distinguish it from septic shock.

Th-(Th1/Th2/Th17)-Cell-Mediated Immunity

Читать дальше