1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...30

1.1.2 Scale and Complexity of Manufacturing

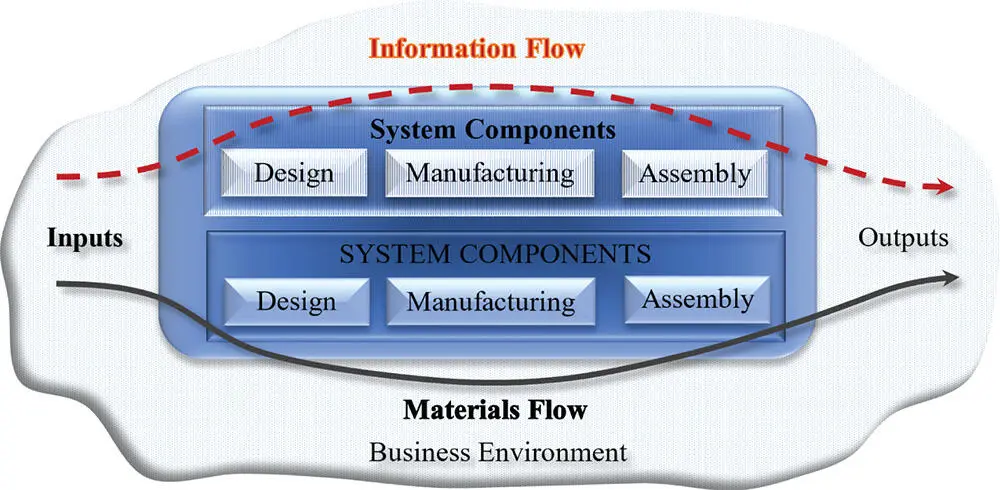

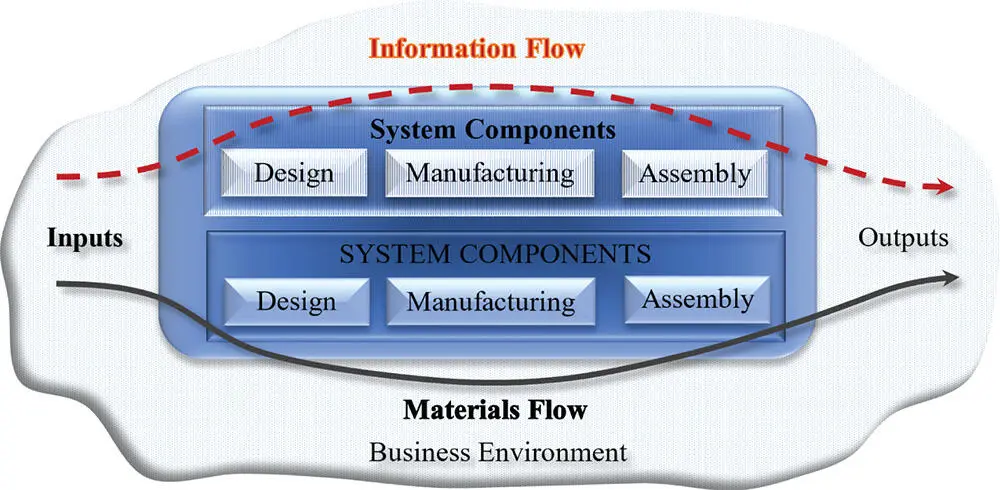

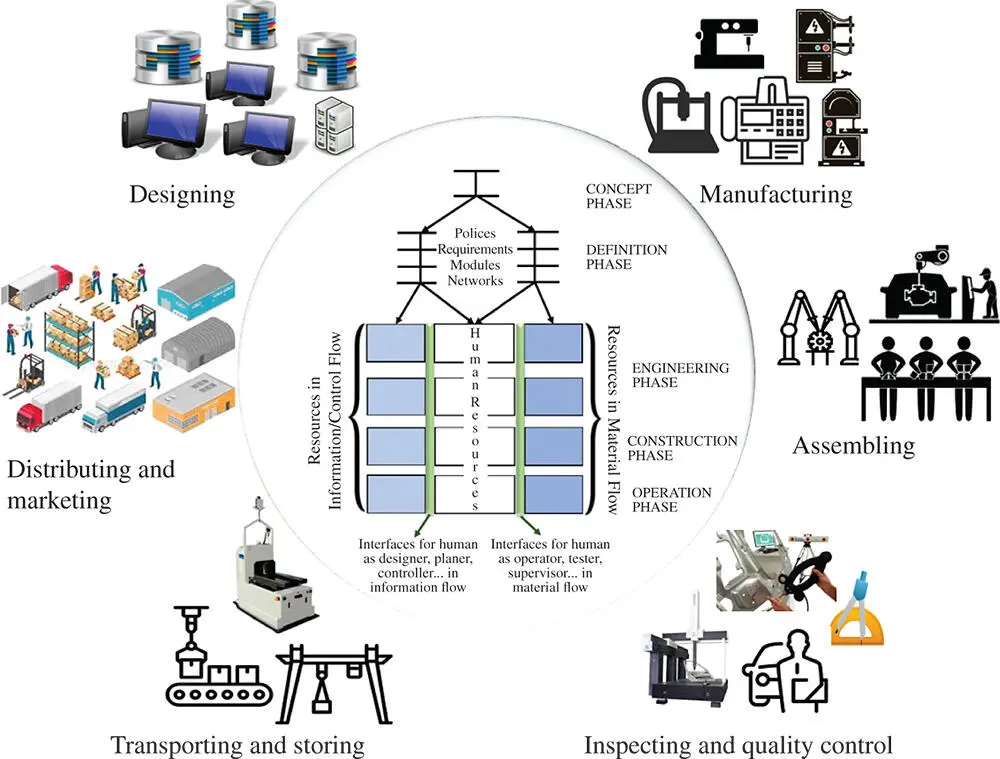

From a system perspective, a manufacturing system can be described by the inputs , outputs , system components , and their relations , as shown in Figure 1.2. The system is modelled in terms of its information flow and materials flow , respectively. System inputs and outputs are involved at the boundaries of a manufacturing system in its surrounding business environment. For example, the materials from suppliers are system inputs and the final products delivered to customers are system outputs. System components include all of the manufacturing resources for designing, manufacturing, and assembling of products as well as other relevant activities such as transportations in the system. In addition, a virtual twin in the information flow is associated with a physical component in the materials flow for decision‐making supports of manufacturing businesses.

Figure 1.2Description of a manufacturing system.

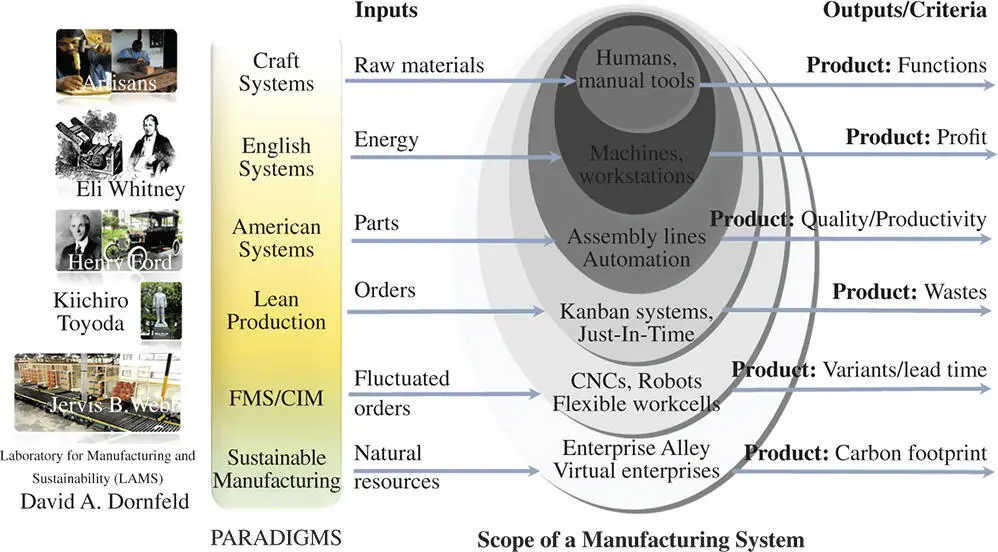

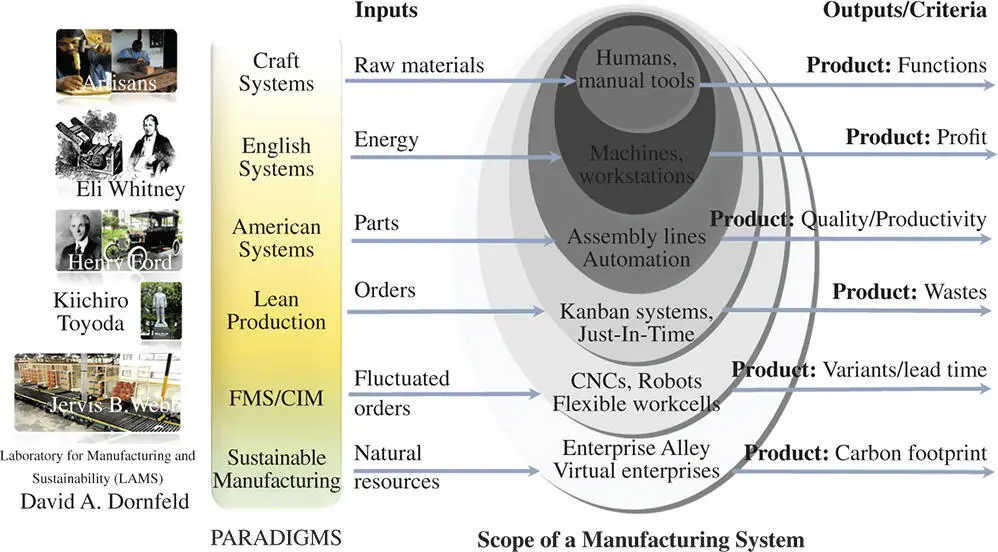

In the evolution of manufacturing technologies, the scale and complexity of manufacturing systems have been growing constantly. Note that both the scale and complexity of a system relates to the number and types of inputs, outputs, and system components that transform inputs to outputs. Figure 1.3shows the impact of the evolution of system paradigms on the complexity of manufacturing systems (Bi et al. 2008). The evolution of system paradigms is divided into the phases of craft systems, English systems, American systems, lean production, flexible manufacturing systems (FMSs), computer integrated manufacturing (CIM), and sustainable manufacturing.

Figure 1.3The growth of scale and complexity of manufacturing systems (Bi et al. 2014).

Historically, the manufacturing business began with craft systems where some crude tools were made from objects found in nature. The system inputs were simple objects and the requirements of the products were basic functions. In the 1770s, James Watt improved Thomas Newcomen's steam engines with separate condensers, which triggered the formation of English systems . In an English manufacturing system, machines partially replaced human operators for heavy and repetitive operations, the power supply became an essential part of the manufacturing source, and the production was scaled to make functional products for profit. In the 1800s, Eli Whitney introduced interchangeable parts in manufacturing that allowed all individual pieces of a machine to be produced identically. Thus, mass production became possible, the manufacturing processes began to be distributed, and system inputs in general assembly companies included parts and components. The criteria of system performance were prioritized with productivity and product quality. Mass production in the American system paradigm brought the rapid growth of manufacturing capacities that led to the saturation of manufacturing capacities in comparison with global needs. The global market became so competitive that the profit margin was such that without consideration of cost savings in the manufacturing processes profits would be insufficient to sustain manufacturing business. The lean production paradigm was conceived in Japan to optimize system operation by identifying and eliminating waste in production, thus reducing product cost to compensate for the squeezed profit margin. Most recently, sustainable manufacturing paradigms were developed to optimize manufacturing systems from the perspective of the product life cycle. This was driven by a number of factors, such as global warming, environmental degradation, and scarcity of natural resources. Manufacturing system paradigms are continuously evolving. The trend of the evolution in Figure 1.3has shown that manufacturing systems are becoming more and more complicated in terms of the number of system parameters , the dependence on system parameters , and their dynamic characteristics with respect to time. The engineering education for human resources must evolve to meet the growth needs of the manufacturing industry.

1.1.3 Human Roles in Manufacturing

Computer aided technologies (CATs) in manufacturing are of the most interest in this book and are widely adopted to replace humans in various manufacturing activities and decision‐making supports. To appreciate the applications of CATs, the roles of the human being in manufacturing systems are firstly discussed to explore the possibilities of automated solutions.

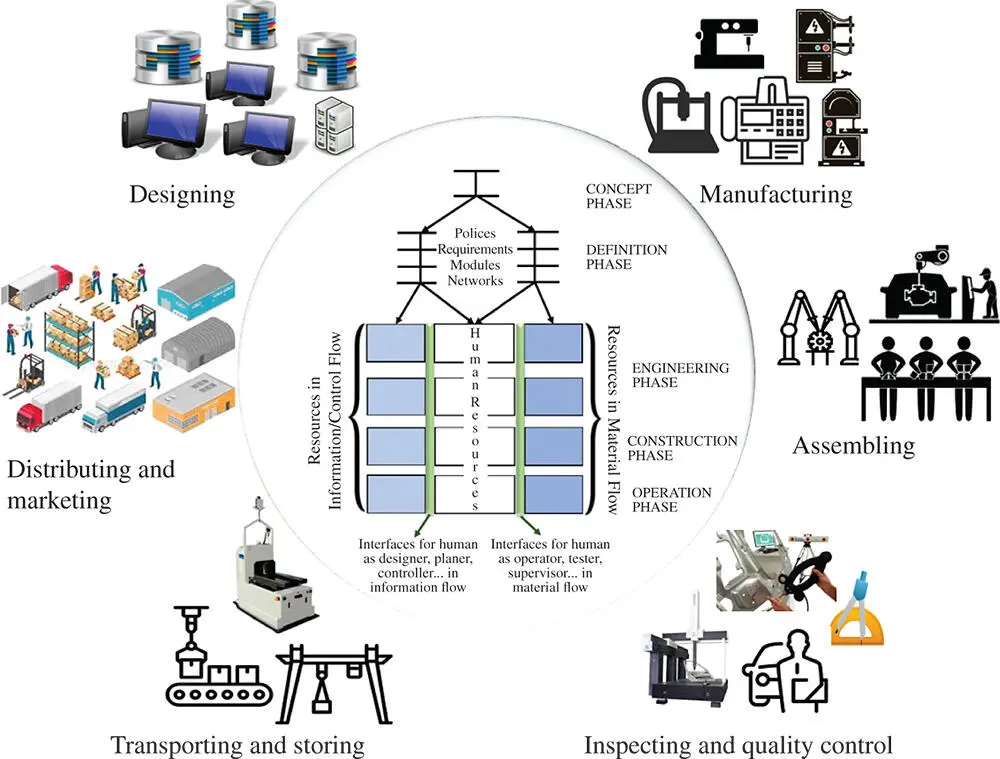

As shown in Figure 1.4, the importance of human being in a manufacturing system has been widely discussed. In developing the Purdue system architecture, Li and Williams (1994) classified manufacturing activities into the activities in information/control flow and material flow, respectively. Human resources are needed to accomplish the tasks in both information and material flows. For example, human labourers are commonly seen in an assembly plant to accomplish manual assemblies in the material flow; technicians are needed by small and medium sized companies (SMEs) to generate codes and run computer numerical controls (CNCs) in the information/control flow. From the perspective of a product lifecycle (Ortiz et al. 1999), human resources are needed at every stage from designing to manufacturing, assembling, inspecting, transporting, marketing, and so on.

Figure 1.4Human's role in manufacturing (Ortiz et al. 1999).

Human resources will certainly play an essential role in the future of manufacturing where manufacturing technologies and human beings are being integrated more closely and more harmoniously than ever before. While the focus should be shifted to the effective human–machine interactions to synergize both strengths of human beings and machines, manufacturing technologies should be advanced to balance the strengths and limitations of human resources optimally.

With the rapid development of information technologies (IT), CATs are replacing human beings for more and more decision‐making support. The design and operation of a manufacturing system involves numerous decision‐making undertakings at all levels and domains of manufacturing activities. In any engineering decision‐making problem, one can follow the generic procedure with a series of design activities: (i) defining the scope and boundary of a design problem and its objective, (ii) establishing relational models among inputs, outputs, and system parameters, (iii) acquiring and managing data on current system states, and (iv) making decisions according to given design criteria. In the information flow of a manufacturing system, each entity normally has its capabilities to acquire the input data, process data, and make the decision as an output data.

1.1.4 Computers in Advanced Manufacturing

The performance of a manufacturing system can be measured by many criteria. Some commonly used evaluation criteria are lead‐time , variants , and volume s of products, as well as cost (Bi et al. 2008). Manufacturing technologies have advanced greatly to optimize system performances. Figure 1.5gives a taxonomy of available enabling technologies in terms of the strategies , domains , and product paradigms of businesses to optimize systems against the aforementioned evaluation criteria. In the implementation of production, the majority of advanced technologies, such as CIM, FMS, Concurrent Engineering (CE), Additive Manufacturing (AM), and Total Quality Management (TQM), are enabled by CATs.

Читать дальше