Mechanical adhesion occurs “whenever a liquid adhesive penetrates into the porous adherend and solidifies in situ in the pores”. Examples are adhesion to wood, unglazed porcelain, pumice, and charcoal.

The surface of a substrate is never truly smooth but consists of a maze of peaks and valleys. This type of topography allows adhesive to penetrate and fill these valleys, displace the entrapped air, and secure mechanically in position inside the substrate similar to the operation of the Velcro.

Porosity and roughness of the substrate increase the total area of contact between the adhesive and the adherend. Hence, roughening the adherend surface enhances the mechanical interlocking since total effective area over which the forces of adhesion can develop increases. The mechanical adhesion theory does not take into account the intrinsic incompatibility between the adhesive and the substrate.

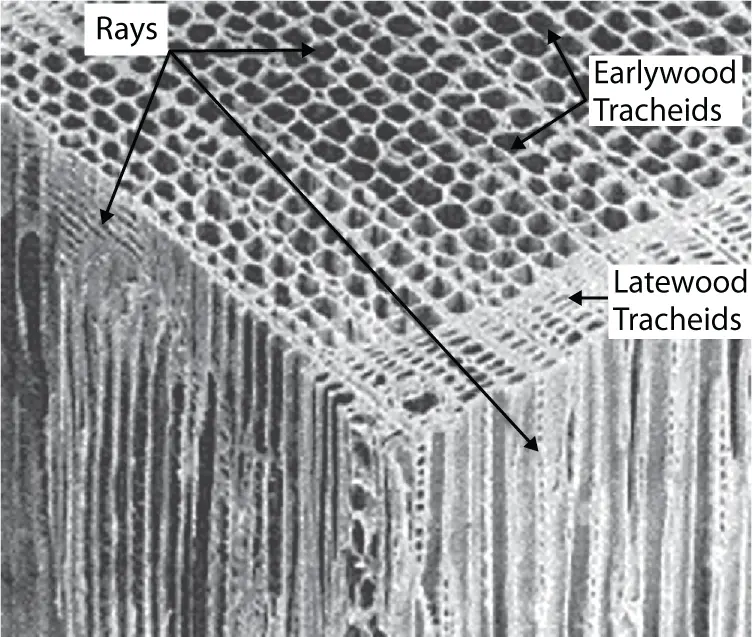

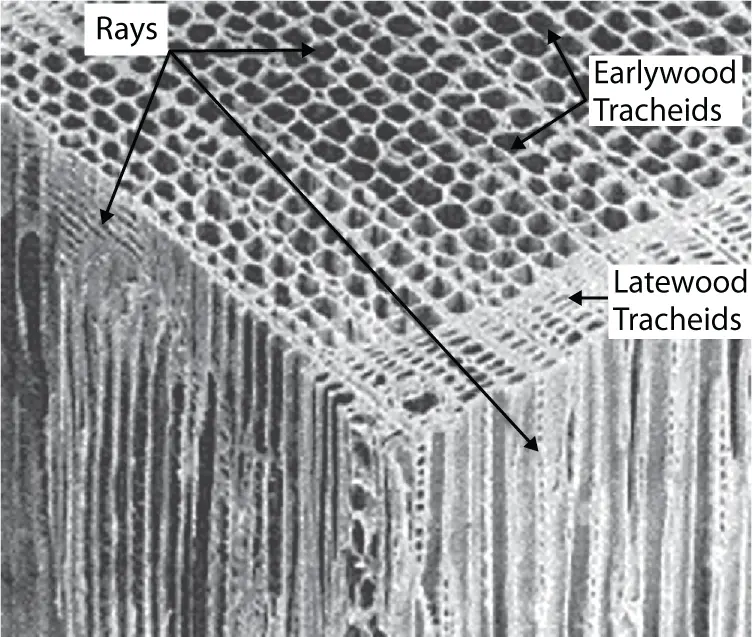

2.4.1.1 lllustration of Mechanical Adhesion for Wood

In wood adherends, there is a vast array of void spaces as shown in Figure 2.2. Spontaneous surface wetting and capillary effects allow the flow of the adhesive resin into the cell lumen, vessels, or other interstices followed by subsequent hardening of the resin and resulting in mechanical interlocking. The resin acts to reinforce the surface/interface layers of wood cells. An adhesive penetration of approximately 6–10 cell diameters (fewer than 100 μm, maximum) is regarded as necessary for optimal adhesive bonding. Filling the cell lumen with adhesive provides much larger mechanical interlocks than are available with surface roughness for other substrates. Absorption into the cell wall can provide micromechanical interlocks and interpenetrating networks [1].

Figure 2.2 Various wood elements.

This theory was mainly promoted by Deryaguin [14–16]. If the adhesive and the substrate have different electronic band structures, there is likely to be electron transfer on contact between the two surfaces. This results in the promotion of a double layer of electrical charges at the adhesive substrate interface. Electrostatic forces are formed at the adhesive–adherent interface. This accounts for the resistance to separation. This theory gathers support from the fact that electrical discharges have been noticed when an adhesive is peeled from a substrate. Electrostatic adhesion is regarded as a dominant factor in biological cell adhesion and particle adhesion. No application of this theory to wood appears possible.

The electronic theory

Depends on material properties that allow electron transfer across the interface

Requires intimate contact/smooth surfaces

Interactions are very weak and rather insignificant

Mechanism is not important for wood substrates

The diffusion theory was proposed in the early 1960s by Voyutskii [17–19]. It states that the intrinsic adhesion of a resin to a polymeric substrate is due to mutual diffusion of polymer molecules across their interface.

As a result of this interdiffusion of molecules of the adhesive and adherend, their interface disappears. Hence, the diffusion theory is applicable only when both adhesive and adherend are compatible polymers that possess sufficient mobility and mutual solubility. Solvents or heat welding of thermoplastic substances is caused by diffusion.

The prerequisite of the diffusion theory is that the polymers of the adhesive and of the substrate should possess similar values of solubility parameters.

Several problems are encountered when an attempt is made to apply the diffusion theory to wood. Basically, wood is not homogeneous in composition. It is a cellular composite of three polymers, namely, cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin. Furthermore, cellulose consists of both crystalline and amorphous regions. It is clear then from solubility parameter concepts that some polymers, the amorphous ones such as hemicelluloses and lignin and the amorphous portion of cellulose, could, under some conditions, undergo mutual diffusion with the polymer chains of the synthetic adhesives. The crystalline portion of cellulose is not likely to be involved.

There is one specific instance in the case of wood adhesion [17] in which interdiffusion appears to exist and is likely to play a significant role in wood bonding. This is the production of fiberboard by the wet process in which no adhesive is added. At high moisture content, high temperature and pressure and long pressing times, the glass transition temperatures of lignin are exceeded. Thus, the lignin in the fibers is mobilized and the interdiffusion between lignin polymers on different fibers contributes to the bonding of the fibers together.

2.7 Adsorption/Covalent Bond Theory

The adsorption theory of adhesion, and the most widely accepted one, in wood science, which is sometimes also called “specific adhesion” [20], states that an adhesive will adhere to a substrate because of intermolecular and interatomic forces between the atoms and molecules of the two materials. The interatomic and intermolecular forces referred to can be any type of either primary or secondary valency forces. van der Waals forces, hydrogen bond, and electrostatic forces are as much applicable as the primary valence forces such as ionic, covalent metallic coordination bonds. In the case of wood adhesion, however, there is an age-old mistaken notion that covalent linkages must be present to ensure good joint strength. In fact, covalent bonding theory was invoked to explain the durable wood bonding with thermosetting adhesives. But as mentioned by Gardner [21], it is very likely that covalent bonds between the wood and adhesive are not necessary for durable wood adhesive bonds.

Calculations carried out by a number of authors based on the secondary forces involved indicate that the wood bond strength in tension should be over 100 MPa. This is considerably higher than the experimental values obtained in the case of several wood adhesives. This discrepancy could be due to the presence of voids, defects, and the geometrical features of the test specimen. Pizzi concludes that these studies indicate that the secondary valency forces themselves are adequate to explain the practical results and it is not necessary to invoke the involvement of covalent bonds [20]. An elaborate discussion on the relative importance of the primary and secondary valence forces has been furnished by Pizzi based on the adhesive strengths obtained from wood joints and the common wood adhesives such as phenolics, amino resins, and isocyanates [20].

2.8 Adhesion Interactions as a Function of Length Scale

It is useful to know the scale of lengths over which the adhesion interactions as described above do occur ( Table 2.2) [21]. It is apparent from Table 2.2that the adhesive interactions relying on interlocking or entanglement can occur over larger lengths than the adhesion involving charge interactions. Most of the charge interactions occur at the molecular level or the nano-length scale. Electrostatic interactions are the exception to this generalization. For the purpose of adhesive interactions, they are considered to operate from a nano- to a micron-length scale.

Table 2.2 Comparison of adhesion interactions relative to length scale.

| Category of adhesion |

|

| Mechanism |

Type of interaction |

Length scale |

| Mechanical |

Interlocking or entanglement |

0.01–1000 μm |

| Diffusion |

Interlocking or entanglement |

10 nm-2 mm |

| Electrostatic |

Charge |

0.1–1.0 μm |

| Covalent bonding |

Charge |

0.1–0.2 nm |

| Acid-base interaction |

Charge |

0.1–0.4 nm |

| Lifshitz van der Waals |

Charge |

0.5–1.0 nm |

2.9 Wetting of the Substrate by the Adhesive

Читать дальше