FIGURE 2-11:These magnifying goggles (used by watchmakers and model makers) are a great beekeeping tool for finding those itty-bitty eggs.

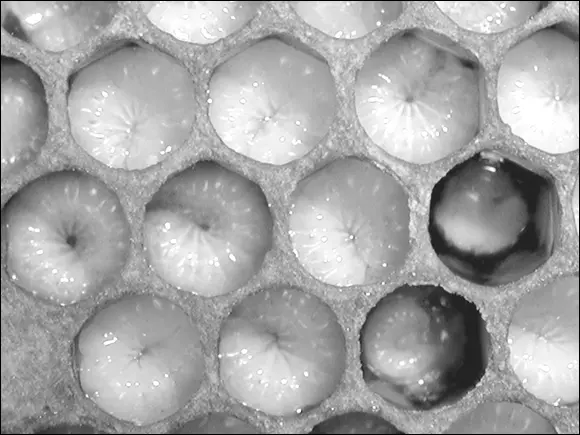

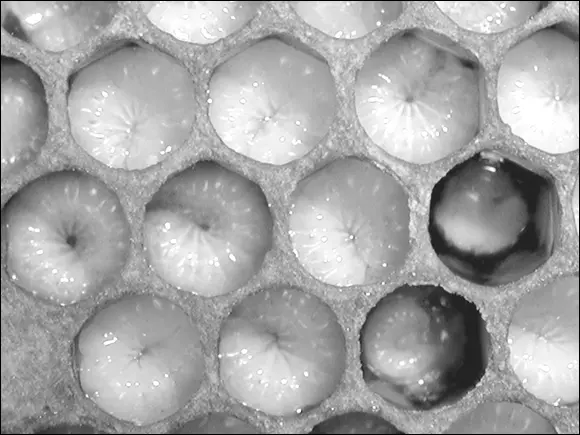

Three days after the queen lays the egg, it hatches into a larva (the plural is larvae ). Healthy larvae are glistening and snowy white and resemble small grubs curled like the letter C in the cells (see Figure 2-12). Tiny at first, the larvae grow quickly, shedding their skin five times. These helpless little creatures have voracious appetites, consuming meals 24 hours a day. The nurse bees first feed the larvae royal jelly, and later they’re weaned to a mixture of honey and pollen (sometimes referred to as bee bread ). Within just five days, they are 1,500 times larger than their original size. At this time the worker bees seal the larvae in the cell with a porous capping of tan beeswax. Once sealed in, the larvae spin a cocoon around their bodies.

Courtesy of John Clayton

FIGURE 2-12:Beautiful, pearly white little larvae curled up in their cells.

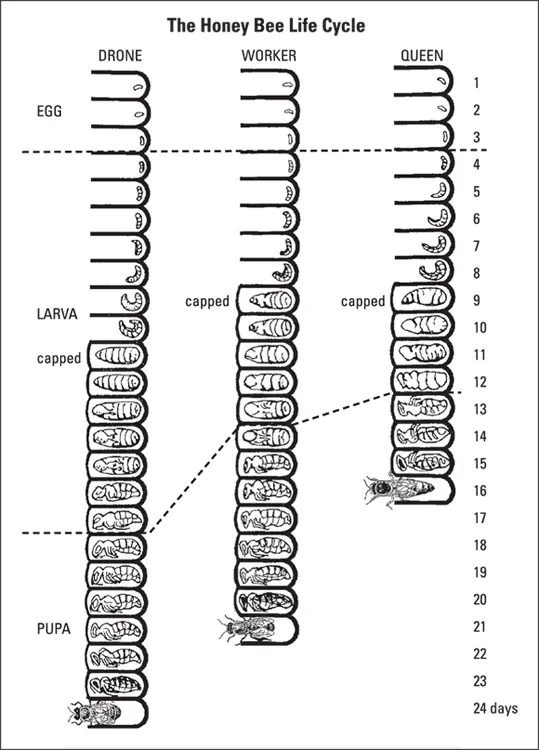

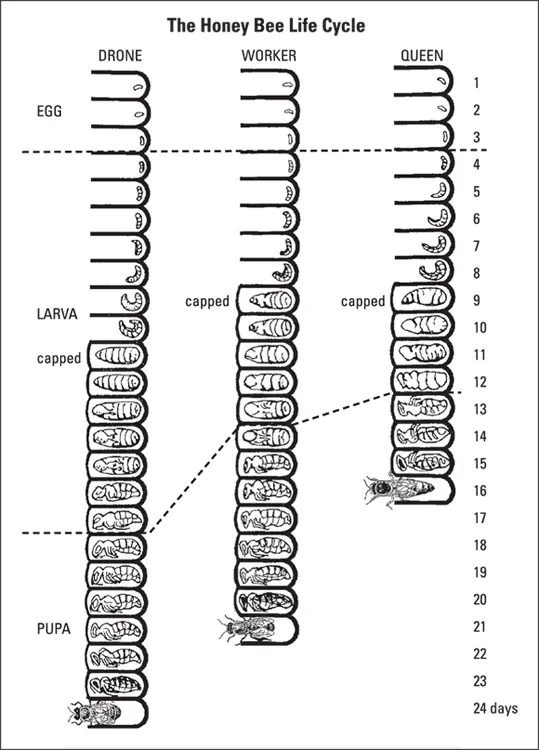

The larva is now officially a pupa (the plural is pupae ). Here’s where things really begin to happen but are not visible to the beekeeper The changes are hidden from sight under the wax cappings. But if you could, you’d see that this little creature is quickly beginning to take on the familiar features of an adult bee (see Figure 2-13). The eyes, legs, and wings take shape. Coloration begins with the eyes: first pink, then purple, and then black. Finally, the fine hairs that cover the bee’s body develop. After 12 days (in the case of the worker) the adult bee is now ready to chew her way through the wax capping to join her sisters and brothers. Figure 2-14 shows the entire life cycle, from start to finish, of the drone, worker and queen honey bees.

Courtesy of Dr. Edward Ross, California Academy of Sciences

FIGURE 2-13:Opened cells reveal an egg and developing pupae.

Courtesy of Howland Blackiston

FIGURE 2-14:This chart shows the daily development cycle of the two female castes and the drone, from egg to adult.

Many people are quick to say they’ve been “stung by a bee,” but the chances of a honey bee stinging them are rather slim. Honey bees usually are gentle in nature, and it is rare for an individual to be randomly stung by a honey bee. Honey bees sting as a defensive behavior; they are most likely to sting around the hive or when disturbed while foraging on a flower.

Other stinging insects, especially some of the wasps, are the more likely culprits to sting someone. Most folks, however, don’t make the distinction between honey bees and wasps. They incorrectly lump all insects with stingers into the “bee” category. True bees are unique in that their bodies are covered with hair, and they use pollen and nectar from plants as their sole source of food (they’re not the ones raiding your hamburger at a picnic — those are likely to be yellow-jacket wasps). Here are some of the most common stinging insects.

The gentle bumble bee, sometimes called a humble bee (see Figure 2-15), is large, plump, mostly black and yellow, and hairy. It’s a familiar sight, buzzing loudly from flower to flower, collecting pollen and nectar. Bumblebees live in small ground nests, and all but newly reared next season queens die off every autumn. At the peak of summer, the colony is only a few hundred strong. Bumble bees make honey, but only small amounts (measured in ounces, not pounds). They are generally quite docile and not inclined to sting unless they or their nest is disturbed.

Courtesy of Dr. Edward Ross, California Academy of Sciences

FIGURE 2-15:The bumble bee is furry and plump.

The carpenter bee (see Figure 2-16) looks much like a bumble bee, but its habits are quite different. It is a solitary bee that makes its nest by tunneling through solid wood (sometimes the wooden eaves of a barn or shed). Like the honey bee, the carpenter bee forages for pollen. Its nest is small and produces only a few dozen offspring a season. Carpenter bees are gentle and are not likely to sting. But they can do some serious damage to the woodwork on your house.

Courtesy of Dr. Edward Ross, California Academy of Sciences

FIGURE 2-16:The carpenter bee looks similar to a bumblebee, but its abdomen has no hair.

A bit similar in appearance to honey bees, the mason bee is a very important contributor to effective pollination. Unlike honey bees or bumble bees, mason bees are solitary, meaning there is no queen bee, and every female is fertile, making her own nest. Mason bees produce neither honey nor beeswax. In the wild, they build their mud-sealed nests in natural tubes like reeds or holes in dead trees. There has been a considerable insurgence of interest in these lovely insects, and commercially manufactured nests are available to house mason bees for the pollination of gardens and orchards (see Figure 2-17). Although mason bees do have stingers, they are very gentle. Even if you do get stung, it is more like a mosquito bite than a painful bee, wasp, or hornet sting.

Many different kinds of insects are called wasps. The more familiar of these are distinguished by their smooth, hard bodies (usually brown or black) and distinctive ultra-thin wasp waist (see Figure 2-18). Social wasps build exposed paper nests, which usually are rather small and contain only a handful of adults and brood. There are no food stores. These nests sometimes are located where we’d rather not have them (in a door frame or windowsill). The slightest disturbance can lead to defensive behavior and stings. Social wasps primarily are meat eaters, but adult wasps are attracted to sweets. Note that wasps and hornets have smooth stingers (no barbs) and can inflict their fury over and over again. Ouch!

Courtesy of www.crownbees.com

FIGURE 2-17:A commercially available mason-bee nest.

Courtesy of Dr. Edward Ross, California Academy of Sciences

FIGURE 2-18:The wasp is clearly identified by its smooth, hairless body and narrow wasp waist.

The yellow jacket also is a social wasp. Fierce and highly aggressive, it is likely responsible for most of the stings wrongly attributed to honey bees (see Figure 2-19). Yellow jackets are a familiar sight at summer picnics, where they scavenge for food and sugary drinks. Two basic kinds of yellow jackets exist: those that build their paper nests underground (which can create a problem when noisy lawn mowers or thundering feet pass overhead) and those that make their nests in trees. All in all, yellow jackets aren’t very friendly bugs.

Читать дальше