Jane Flint - Principles of Virology

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jane Flint - Principles of Virology» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Principles of Virology

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Principles of Virology: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Principles of Virology»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Volume I: Molecular Biology

Volume II: Pathogenesis and Control

Principles of Virology, Fifth Edition

Principles of Virology — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Principles of Virology», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

BOX 4.10

DISCUSSION

The extreme pleomorphism of influenza A virus, a genetically determined trait of unknown function

Some enveloped viruses vary considerably in size and shape. For example, the particles of paramyxoviruses, such as measles and Sendai viruses, range in size from 120 to up to 540 nm in diameter and may contain multiple copies of the (−) strand RNA genome in helical nucleocapsids of different pitch. Influenza A virus particles exhibit even more extreme pleomorphism: they appear spherical, elliptical, or filamentous, and all forms come in a wide range of sizes (see the figure). Clinical isolates are primarily filamentous but adopt the spherical morphologies when adapted to propagation in the laboratory, particularly in chicken eggs.

Several lines of evidence indicate that the filamentous phenotype is genetically determined. For example, the particles of some influenza A virus isolates are primarily filamentous, whereas those of other isolates are not. Furthermore, genetic experiments have identified specific residues in the matrix proteins (M1 and M2) required for assembly of filamentous particles. Deletion of the internal domain of the NA glycoprotein also induces formation of elongated particles, a phenotype exacerbated by concurrent removal of the cytoplasmic tail of the major viral glycoprotein HA. These observations imply that matrix-glycoprotein interactions during assembly govern the morphology of influenza A virus particles. However, the mechanism underlying the “choice” between assembly of filamentous versus spherical particles is not well understood and the influence of host cell components remains obscure. Furthermore, the physiological significance of the filamentous particles is not known, despite their predominance in clinical isolates. It has been speculated that these forms might facilitate cell-to-cell transmission of virus particles through the respiratory mucosa of infected hosts.

Badham MD, Rossman JS. 2016. Filamentous influenza viruses. Curr Clin Microbiol Rep 3:155–161.

Cryo-electron tomogram sections of influenza A virus particles (strain PR8).Bar = 50 nm. Reprinted from Nayak DB et al. 2009. Virus Res 143:147–161, with permission. Courtesy of D.B. Nayak, University of California, Los Angeles.

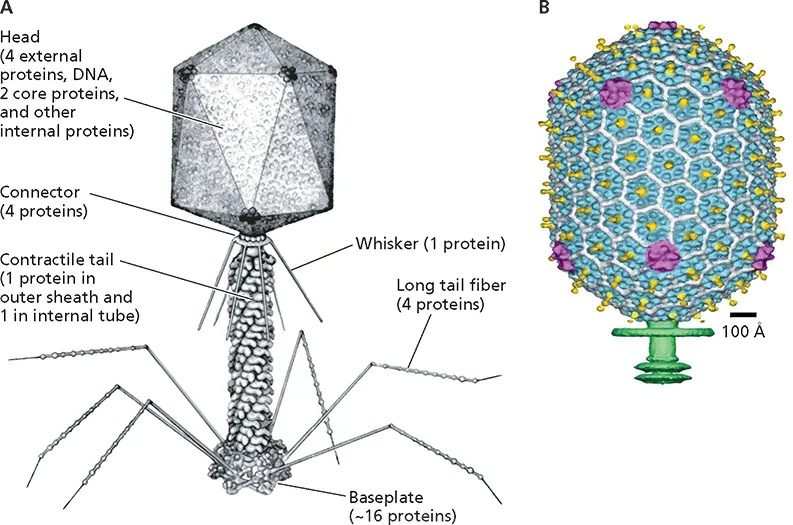

In contrast to the head, the ~100-nm-long tail, which comprises two protein layers, exhibits helical symmetry ( Fig. 4.26A). The outer layer is a contractile sheath that functions in injection of the viral genome into host cells. The tail is connected to the head via a hexameric ring and at its other end to a complex, dome-shaped structure termed the baseplate, where it carries the cell-puncturing spike. Both long and short tail fibers project from the baseplate. The former, which are bent, are the primary receptor-binding structures of bacteriophage T4. As discussed in Chapter 5, remarkable conformational changes induced upon receptor binding by the tips of the long fibers are transmitted via the baseplate to initiate injection of the DNA genome.

Herpesviruses

Members of the Herpesviridae exhibit a number of unusual architectural features. More than half of the >80 genes of herpes simplex virus type 1 encode proteins found in the large (~200-nm-diameter) virus particles. These proteins are components of the envelope from which glycoprotein spikes project or of two distinct internal structures. The latter are the nucleocapsid surrounding the DNA genome and the protein-aceous layer encasing this structure, called the tegument( Fig. 4.27A). Until recently we possessed only relatively low-resolution views (at best, ~7 Å) of herpesviral particles. Technical advances in cryo-EM image reconstruction, including relaxation of icosahedral symmetry restraints, produced high-resolution structures of herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 particles (3.2 to 3.5 Å), by far the largest virus particles to be visualized in such detail. These remarkable achievements confirmed architectural elements of the nucleocapsid shared with smaller virus particles, but also revealed new features.

A single protein (VP5) forms both the hexons and the pentons of the T = 16 icosahedral capsid of herpes simplex virus type 1 ( Fig. 4.27B). Like the structural units of the smaller simian virus 40 capsid, these VP5-containing assemblies make direct contact with one another. However, the segments of VP5 subunits that form the nucleocapsid floor adopt quite different conformations in the pentons and hexons ( Fig. 4.27B). Similarly, specific VP5 regions display distinct arrangements in hexons that abut pentons and those surrounded entirely by other hexons. These differences optimize interactions among the structural units. The large herpesviral capsid, like that of adenoviruses, is further stabilized by additional proteins, including two that form triplexes that link the major structural units. A second property shared with polyomaviruses (and papillomaviruses) is stabilization of the particle by disulfide bonds, which covalently link both subunits of the triplexes and triplexes to VP5 subunits of adjacent hexons to impart rigidity. Such a network of covalent bonds must greatly increase the stability of the large nucleocapsid and may also be necessary to counter the high pressure exerted on this protein shell (see “Mechanical Properties of Virus Particles”).

Figure 4.26 Morphological complexity of bacteriophage T4. (A)A model of the virus particle. (B)Structure of the head (22-Å resolution) determined by cryo-EM, with the major capsid proteins shown in blue (gp23*) and magenta (gp24*), the protein that protrudes from the capsid surface in yellow, the protein that binds between gp23* subunits in white, and the beginning of the tail in green. Reprinted from Fokine A et al. 2004. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:6003–6008, with permission. Courtesy of M. Rossmann, Purdue University.

Although apparently a typical and quite simple icosahedral shell, this viral capsid is in fact an asymmetric structure: 1 of the 12 vertices is occupied not by a VP5 penton but by a unique structure termed the portal. The portal comprises 12 copies of the UL6 protein and is a squat, hollow cylinder that is wider at one end and surrounded by a two-tiered ring at the wider end ( Fig. 4.27C). The incorporation of the portal, which is connected to the viral membrane ( Fig. 4.27D), has important implications for the mechanism of assembly and delivery of viral genomes during entry (see Chapters 13and 5).

The tegument contains >20 viral proteins, viral RNAs, and cellular components. A few tegument proteins are icosahedrally ordered, as a result of direct contacts with the structural units of the capsid. For example, three tegument proteins form a distinctive structure that caps the pentons and buttresses their association with neighboring triplexes. Tegument proteins are notuniformly distributed around the capsid, but are concentrated on one side, where they form a well-defined cap-like structure ( Fig. 4.27A). The connection of the portal vertex of the capsid to the viral membrane ( Fig. 4.27D) seems likely to account for this asymmetry.

Mimiviruses

Characteristic features of members of the Mimiviridae , which infect single-cell eukaryotes, are their very large, double-stranded DNA genomes and correspondingly huge particles. Initial examinations of these viruses by electron microscopy established that they comprise multiple layers, include a lipid membrane within an external capsid, and in some cases include a dense layer of surface fibers ( Fig. 4.1). Despite their large size, mimivirus particles exhibit some familiar structural features, notably icosahedral symmetry and a capsid built from a major capsid protein with the double β-barrel jelly roll topology. To date, cryo-EM reconstructions of these viruses have achieved only a relatively low resolution, because of the need for much computational power (e.g., ~3 × 10 6CPU hours for a 21-Å view of Cafeteria roenbergensis virus ) and/or removal of dense surface fibers (as for a 65-Å reconstruction of Acanthamoeba polyphaga mimivirus) . Such studies have revealed the icosahedral organization of major capsid proteins ( Fig. 4.28) and in some cases their arrangement into assemblies that interact around the five- or threefold axes of symmetry. The most unique feature, first observed in Acanthamoeba polyphaga mimivirus , is the presence of a star-shaped structure at one vertex (Fig 4.28B). This stargate, which allows release of internal contents of virus particles into the cytoplasm of infected cells, is an exceptionally large vertex structure, with arms extending almost to neighboring vertices. As yet, little is known about how such large capsids (up to ~5,000 Å in diameter) are stabilized, or the organization of their internal components.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Principles of Virology»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Principles of Virology» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Principles of Virology» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.