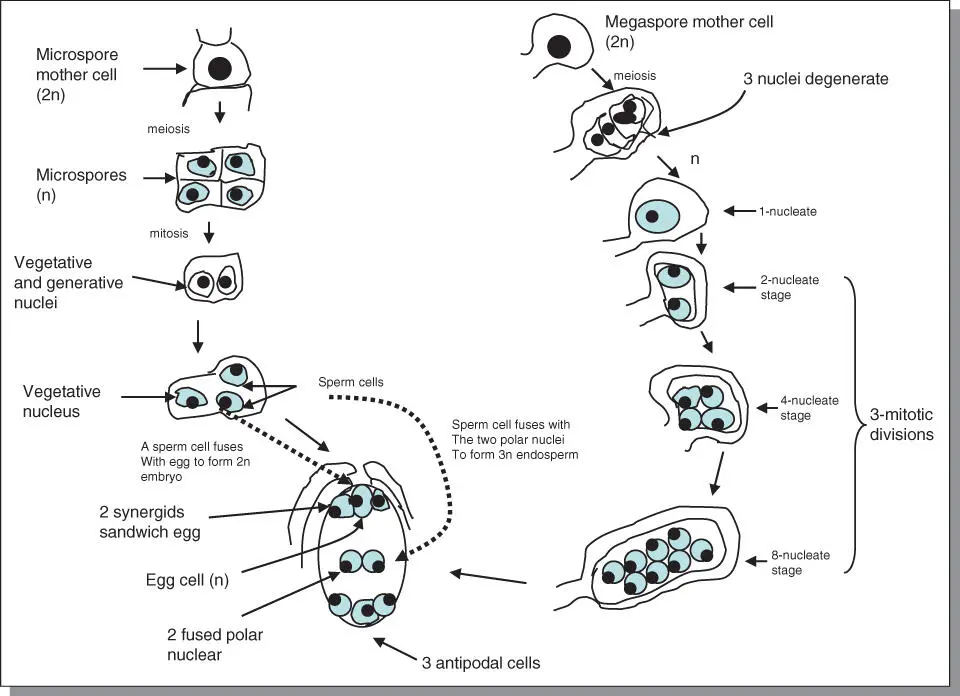

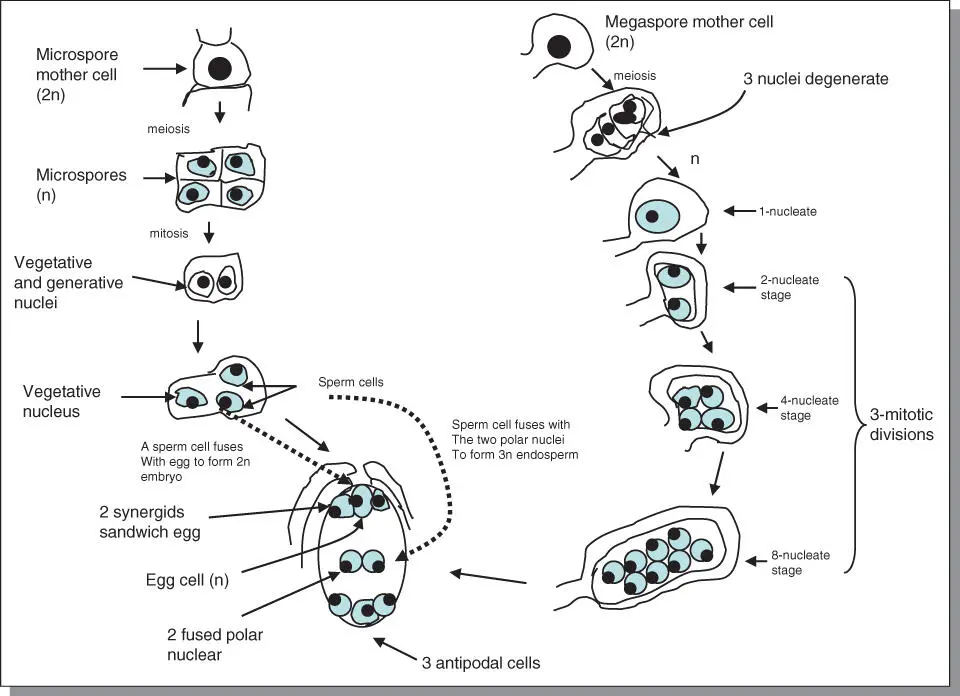

Sexual reproduction entails the transfer of gametes to specific female structures where they unite and are then transformed into an embryo, a miniature plant. Gametes are formed by the process of gametogenesis. They are produced from specialized diploid cells called microspore mother cellsin anthers and megaspore mother cellsin the ovary ( Figure 5.4). Microspores derived from the mother cells are haploid cells each dividing by mitosis to produce an immature male gametophyte(pollen grain). Most pollen is shed in the two‐cell stage, even though sometimes, as in grasses, one of the cells later divides again to produce two sperm cells. In the ovule, four megaspores are similarly produced by meiosis. The nucleus of the functional megaspore divides three times by mitosis to produce eight nuclei, one of which eventually becomes the egg. The female gametophyteis the seven‐celled, eight‐nucleate structure. This structure is also called the embryo sac. Two free nuclei remain in the sac. These are called polar nuclei because they originate from opposite ends of the embryo sac.

Figure 5.4Gametogenesis in plants results in the production of pollen and egg cells. Pollen is transported by agents to the stigma of the female flower, from which it travels to the egg cell to unite with it.

5.4.7 Pollination and fertilization

Pollinationis the transfer of pollen grains from the anther to the stigma of a flower. This transfer is achieved through a vector or pollination agent. The common pollination vectors are wind, insect, mammals, and birds. Flowers have certain features that suit the various pollination mechanisms ( Table 5.1). Insect‐pollinated flowers tend to be showy and exude strong fragrances. Birds are attracted to red and yellow flowers. When compatible pollen falls on a receptive stigma, a pollen tube grows down the style to the micropylar end of the embryo sac, carrying two sperms or male gametes. The tube penetrates the sac through the micropyle. One of the sperms unites with the egg cell, a process called fertilization. The other sperm cell unites with the two polar nuclei (called triple fusion). The simultaneous occurrence of two fusion events in the embryo sac is called double fertilization.

Table 5.1Pollination mechanisms in plants.

| Pollination vector |

Flower characteristics |

| Wind |

Tiny flowers (e.g. grasses); dioecious species |

| Insects |

| Bees |

Bright and showy (blue, yellow); sweet scent; unique patterns; corolla provides landing pad for bees |

| Moths |

White or pale color for visibility at night; strong penetrating odor emitted after sunset |

| Beetles |

White or dull color; large flowers; solitary or inflorescence |

| Flies |

Dull or brownish color |

| Butterflies |

Bright colors (often orange, red); nectar located at base of long slender corolla tube |

| Bats |

Large flower with strong fruity pedicels; dull or pale colors; strong fruity or musty scents, flowers produce copious, thick nectar |

| Birds |

Bright colors (red, yellow); odorless; thick copious nectar |

On the basis of pollination mechanisms, plants may be grouped into two mating systems: self‐pollinatedor cross‐pollinated. Self‐pollinated species accept pollen primarily from the anthers of the same flower (autogamy). The flowers, of necessity, must be bisexual. Cross‐pollinated species accept pollen from different sources. In actuality, species express varying degrees of cross‐pollination, ranging from lack of cross‐pollination to complete cross‐pollination.

Self‐pollination or autogamyoccurs in a wide variety of plant species – vegetables (lettuce, tomatoes, snap beans, endive), legumes (soybean, peas, lima beans), and grasses (barley, wheat, oats). Certain natural mechanisms promote or ensure self‐pollination, specifically cleistogamy and chasmogamy, while other mechanisms prevent self‐pollination (e.g. self‐incompatibility, male sterility).

5.5.1 Mechanisms that promote autogamy

Cleistogamyis the condition in which the flower fails to open. The term is sometimes extended to mean a condition in which the flower opens only after it has been pollinated (as occurs in wheat, barley, and lettuce), a condition called chasmogamy. Some floral structures, such as those found in legumes, favor self‐pollination. Sometimes, the stigma of the flower is closely surrounded by anthers, making it prone to selfing.

Very few species are completely self‐pollinated. The level of self‐pollination is affected by factors including the nature and amount of insect pollination, air current, and temperature. In certain species, pollen may become sterilized when the temperature dips below freezing. Any flower that opens prior to self‐pollination is susceptible to some cross‐pollination. A list of predominantly self‐pollinated species in presented is Table 5.2.

Table 5.2Examples of predominantly self‐pollinated species.

| Common name |

Scientific name |

| Barley |

Hordeum vulgare |

| Chickpea |

Cicer arietinum |

| Clover |

Trifolium spp. |

| Common bean |

Phaseolus vulgaris |

| Cotton |

Gossypium spp. |

| Cowpea |

Vigna unguiculata |

| Eggplant |

Solanum melongena |

| Flax |

Linum usitatissimum |

| Jute |

Corchorus espularis |

| Lettuce |

Letuca sativa |

| Oat |

Avena sativa |

| Pea |

Pisum sativum |

| Peach |

Prunus persica |

| Peanut |

Arachis hypogaea |

| Rice |

Oryza sativa |

| Sorghum |

Sorghum bicolor |

| Soybean |

Glycine max |

| Tobacco |

Nicotiana tabacum |

| Tomato |

Solanum lycopersicum |

| Wheat |

Triticum aestivum |

5.5.2 Mechanisms that prevent autogamy

There are several mechanisms in nature that work to prevent self‐pollination in species that otherwise would be self‐pollinated. These include self‐incompatibility, male sterility, and dichogamy.

Self‐incompatibility(or lack of self‐fruitfulness) is a condition in which the pollen from a flower is not receptive on the stigma of the same flower and hence incapable of setting seed. This happens in spite of the fact that both pollen and ovule development are normal and viable. It is caused by a genetically controlled physiological hindrance to self‐fertilization. Self‐incompatibility is widespread in nature, occurring in families such as Poaceae, Cruciferae, Compositae, and Rosaceae. The incompatibility reaction is genetically conditioned by a locus designated S , with multiple alleles that can number over 100 in some species such as Trifolium pretense . However, unlike monoecy and dioecy, all plants produce seed in self‐incompatible species.

Читать дальше