The fire’s impact was so great that a national disaster fund was launched to relieve the destitute citizens, and the first contribution was made by Queen Victoria herself. The Illustrated London News reported a striking example of Victorian philanthropy: ‘The public sympathy for the numerous poor families, who were rendered destitute by this terrible catastrophe, was displayed in the most marked manner throughout the kingdom. Upwards of £11,000 were subscribed for their relief. No less than eight hundred families applied for assistance from the funds …’ Money was also given to institutions like the Newcastle Infirmary and the Gateshead Dispensary. The image of the burning northern industrial city, with its displaced citizens wandering the streets like lost souls in purgatory, struck very deep. It was said that Queen Victoria, in an unprecedented departure from royal protocol, ordered that the royal train on the way to Balmoral should halt on the famous High Level Bridge above Gateshead so she could look down at the devastated city and weep.

Balloons were also used to celebrate colonial cities, and inspire imperial links, notably in Australia. In 1858 the British balloon the Australian made some startling flights over Melbourne and Sydney. There was a late-summer-night ascent in March from Cremorne Gardens, Melbourne, in which a basketful of local dignitaries sailed over the Botanical Gardens in bright moonlight, with a magical sight of the festival fireworks far below. But, attempting to land at Battam’s Swamp, they found themselves in a working-class district, and the balloon basket was seized by a violent crowd. Amid vocal democratic objections to such ‘superior’ transport, the distinguished guests were forced to escape by jettisoning champagne bottles, picnic hampers, several bags of sand ballast, and finally throwing off a few hardy objectors still clinging to the sides of the basket. Unlike America, ballooning in Australia remained an essentially urban entertainment. There is no record of any practical attempts to explore the Australian interior by balloon at this time. Burke and Wills, starting on their epic journey from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria in August 1860, stuck firmly and fatally to the ground. fn15

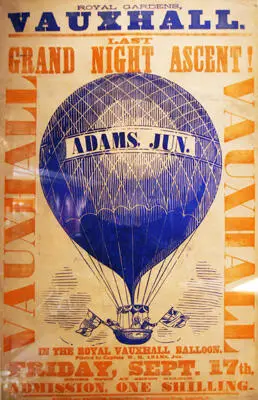

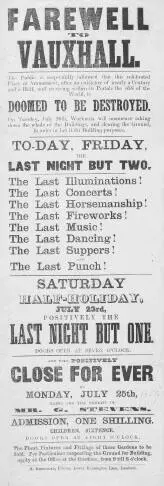

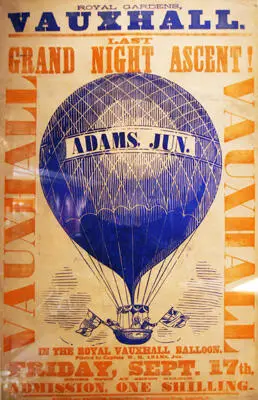

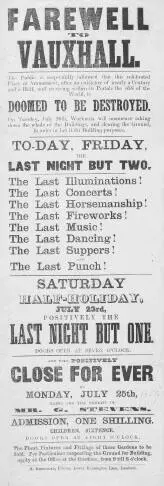

Vauxhall Gardens finally closed after its ‘Last Night for Ever’ on 26 July 1859. Many reasons were given for this. The proprietors blamed the magistrates who continually banned their most popular attractions as either too dangerous, or too disruptive to the newly respectable neighbourhood of Kennington. Ballooning and fireworks displays were particularly blamed for this. But other factors certainly played a part: the gardens had become run-down and tawdry, and were considered old-fashioned; the railway, which ran past the main entrance, had made travel further afield much easier and cheaper; seaside towns, with their Vauxhall-like piers, were becoming fashionable; and, finally, the site itself was too valuable as property, and the blandishments of developers eventually persuaded the proprietors to sell up. 9

At about this time Charles Green, after more than five hundred successful ascents and now in his seventies, also went into retirement. He purchased an elegant little house on a hillside above the Holloway Road, North London, and named it ‘Aerial Villa’. But he kept a weather eye on the horizon.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.