Sahib

The British Soldier In India 1750-1914

Richard Holmes

To Lizzie, Jessica and Corinna, the women in my life

Cover Page

Title Page Sahib The British Soldier In India 1750-1914 Richard Holmes

Dedication To Lizzie, Jessica and Corinna, the women in my life

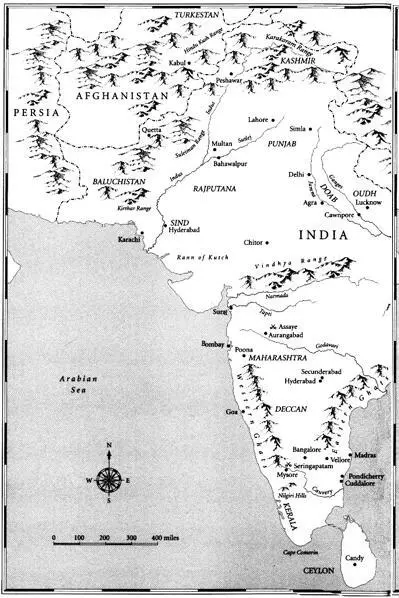

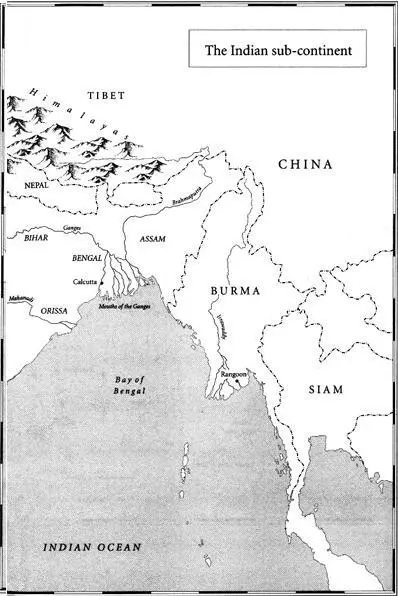

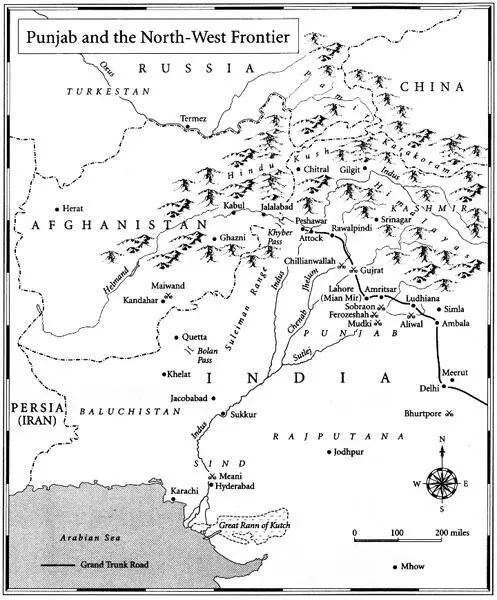

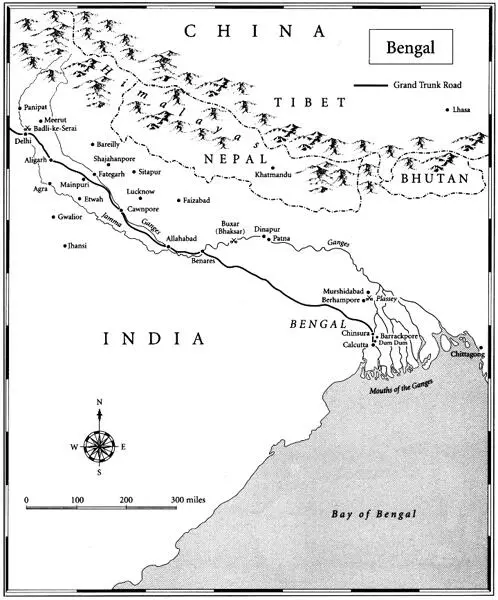

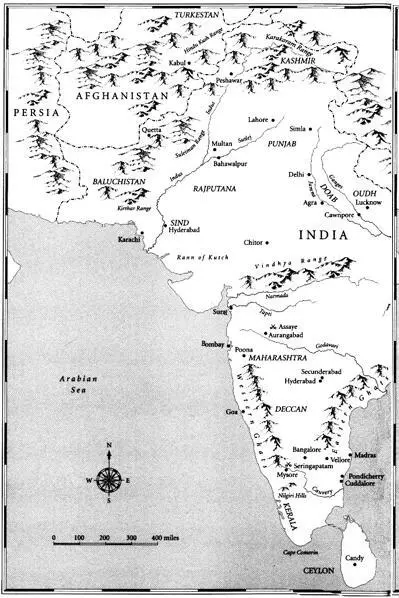

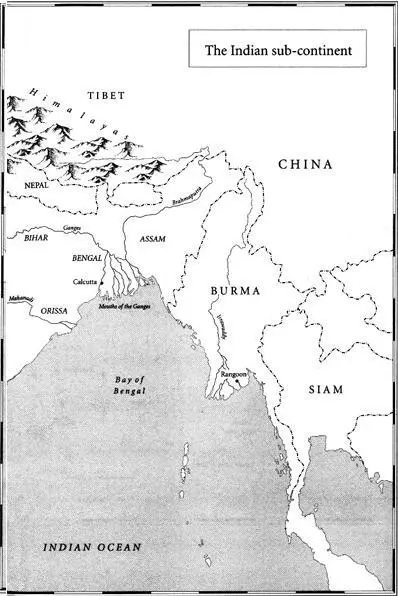

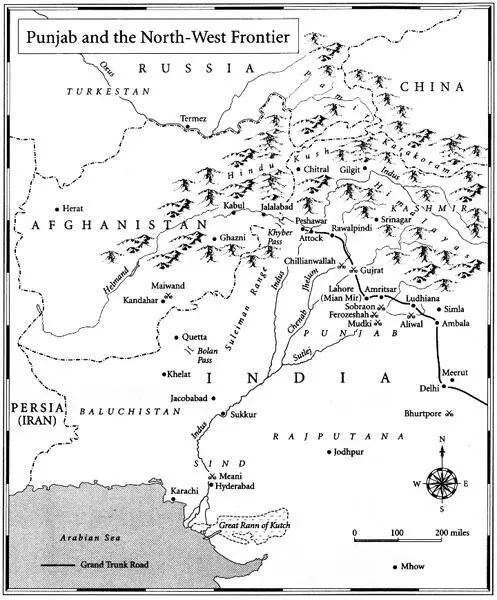

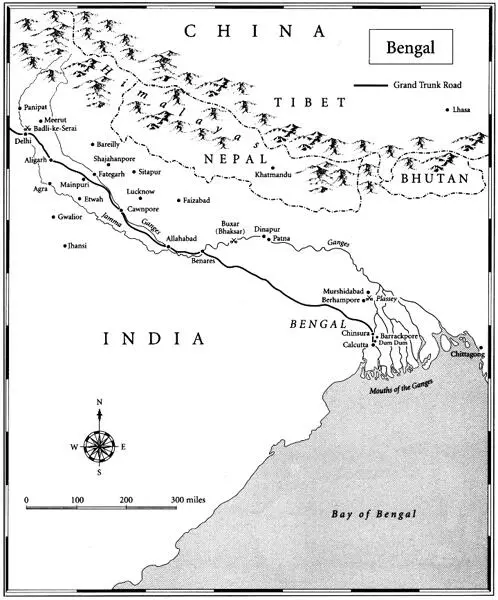

Maps MAPS The Indian sub-continent Punjab and the North-West Frontier Bengal

Epigraph Riding through the densely packed bazaars of Bareilly City on Judy, my mare, passing village temples, cantering across the magical plains that stretched away to the Himalayas, I shivered at the millions and immensities and secrecies of India. I liked to finish my day at the club, in a world whose limits were known and where people answered my beck. An incandescent lamp coughed its light over shrivelled grass and dusty shrubbery; in its circle of illumination exiled heads were bent over English newspapers, their thoughts far away, but close to mine. Outside, people prayed and plotted and mated and died on a scale unimaginable and uncomfortable. We English were a caste. White overlords or whiter monkeys – it was all the same. The Brahmins made a circle within which they cooked their food. So did we. We were a caste: pariahs to them, princes in our own estimation. F. YEATS-BROWN, Bengal Lancer

INTRODUCTION

PROLOGUE

I IN INDIA’S SUNNY CLIME

THE LAND OF THE PAGODA TREE

EMPIRES RISE AND WANE

THE HONOURABLE COMPANY

‘THE DEVIL’S WIND’

THE BRITISH RAJ

II THE TROOPSHIPS BRING US

A PASSAGE TO INDIA

SOMETHING STRANGE TO US ALL

SUDDER AND MOFUSSIL

BARRACKS AND BUNGALOWS

CALLING CARDS AND DRAWING ROOMS

BOREDOM AND BAT

III BREAD AND SALT

LORDS OF WAR

SOLDIERS WITHOUT REGIMENTS

HORSE, FOOT AND GUNS

SALT AND GOLD

IV THE SMOKE OF THE FUSILLADE

FIELDS OF BATTLE

BROTHERS IN ARMS?

GOLD EPAULETTES, SILVER MEDALS

DASH AT THE FIRST PARTY

SHOT AND SHELL

BLACK POWDER AND COLD STEEL

BOOT AND SADDLE

THE PETTAH WALL

DUST AND BLOOD

V INDIA’S EXILES

ARRACK AND THE LASH

BIBIS AND MEMSAHIBS

CHRISTIAN SOLDIERS

A FAMILIAR FRIEND

HOT BLOOD, BAD BLOOD

A NOBLE WIFE

EPILOGUE

GLOSSARY OF INDIAN TERMS

Bibliography

ACKNOWLEGDGEMENTS

NOTES

INDEX

P.S.

About the author

About the book

Read on

About the Author

Praise

ALSO BY RICHARD HOLMES

Copyright

About the Publisher

The Indian sub-continent

Punjab and the North-West Frontier

Bengal

Riding through the densely packed bazaars of Bareilly City on Judy, my mare, passing village temples, cantering across the magical plains that stretched away to the Himalayas, I shivered at the millions and immensities and secrecies of India. I liked to finish my day at the club, in a world whose limits were known and where people answered my beck. An incandescent lamp coughed its light over shrivelled grass and dusty shrubbery; in its circle of illumination exiled heads were bent over English newspapers, their thoughts far away, but close to mine. Outside, people prayed and plotted and mated and died on a scale unimaginable and uncomfortable. We English were a caste. White overlords or whiter monkeys – it was all the same. The Brahmins made a circle within which they cooked their food. So did we. We were a caste: pariahs to them, princes in our own estimation.

F. YEATS-BROWN, Bengal Lancer

Like it or not, the British conquest and dominion of India is one of history’s great epics. A vast, populous and geographically varied continent half a world away from these islands was dominated for over 300 years by a relatively small number of British. It is no exaggeration to say that India was indeed the ‘jewel in the crown’ of the Empire, with a unique place in public and official estimation in general and in the history of the British army in particular. ‘The British conquered India by military force,’ proclaimed the distinguished Indian civil servant Sir Penderel Moon, ‘and the campaigns and battles by which this was achieved … were historical events without which Britain’s Indian empire would never have come into existence.’ 1

It is remarkable to see how much was accomplished by so few. When Queen Victoria came to the throne in 1837, the European population living in India numbered around 41,000, about 37,000 of whom were soldiers; another 1,000 worked for the Indian Civil Service and about another 30,000 of the population was of racially mixed parentage. There was a native population of at least 15 million, less than 200,000 of whom served in the army of the Honourable East India Company, the commercial corporation which, in what is perhaps the most striking example of the flag following trade, actually ran the subcontinent until the British government assumed its responsibilities in 1858.

Historians are unsure whether British rule was a good thing or a bad thing, with two real heavyweights in the debate having disputed the matter recently. In Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order, Niall Ferguson declared that: ‘The question is not whether British imperialism was without blemish. It was not. The question is whether there could have been a less bloody path to modernity.’ His answer is generally negative, arguing that the Empire brought ‘free markets, the rule of law … and relatively incorrupt government’. 2Linda Colley is rather less admiring. In Captives: Britain, Empire and the World, she identifies a strong undercurrent of imperial racism, not least amongst the ‘poor whites’ who provided the shock troops of Empire. 3There is little unanimity amongst Indian historians, for while some look upon the whole imperial episode as an obnoxious aberration, others see value and an enduring benevolent legacy in the British contribution. The Indian historian Kusoom Vadgama writes that ‘independent India is richer for the railways, the telegraphic systems, education, legal and parliamentary procedures based on the British models’ and suggests that it was in fact the Quit India movement of 1942 that pushed Britain towards premature withdrawal and partition. 4But as Moon observed, while the Empire ‘has been both lauded and execrated with undiscriminating fervour – its establishment was an achievement that ought to excite wonder’. 5

And so this is neither a book about the rights or wrongs of the Indian Empire, nor a history of its rise and fall (for the latter Lawrence James’s Raj: The Making and Unmaking of British India stands pre-eminent as a readable popular survey). Instead, I seek to illuminate the central paradox of the Raj: how did a relatively small number of British soldiers gain and retain control of the subcontinent? What encouraged them to go to India; what did they make of an environment so very different to their own; how did they live there and, no less to the point, how did they die?

Читать дальше