PENELOPE FITZGERALD

The Knox Brothers

with an introduction by Richard Holmes

Edmund 1881–1971

Dillwyn 1884–1943

Wilfred 1886–1950

Ronald 1888–1957

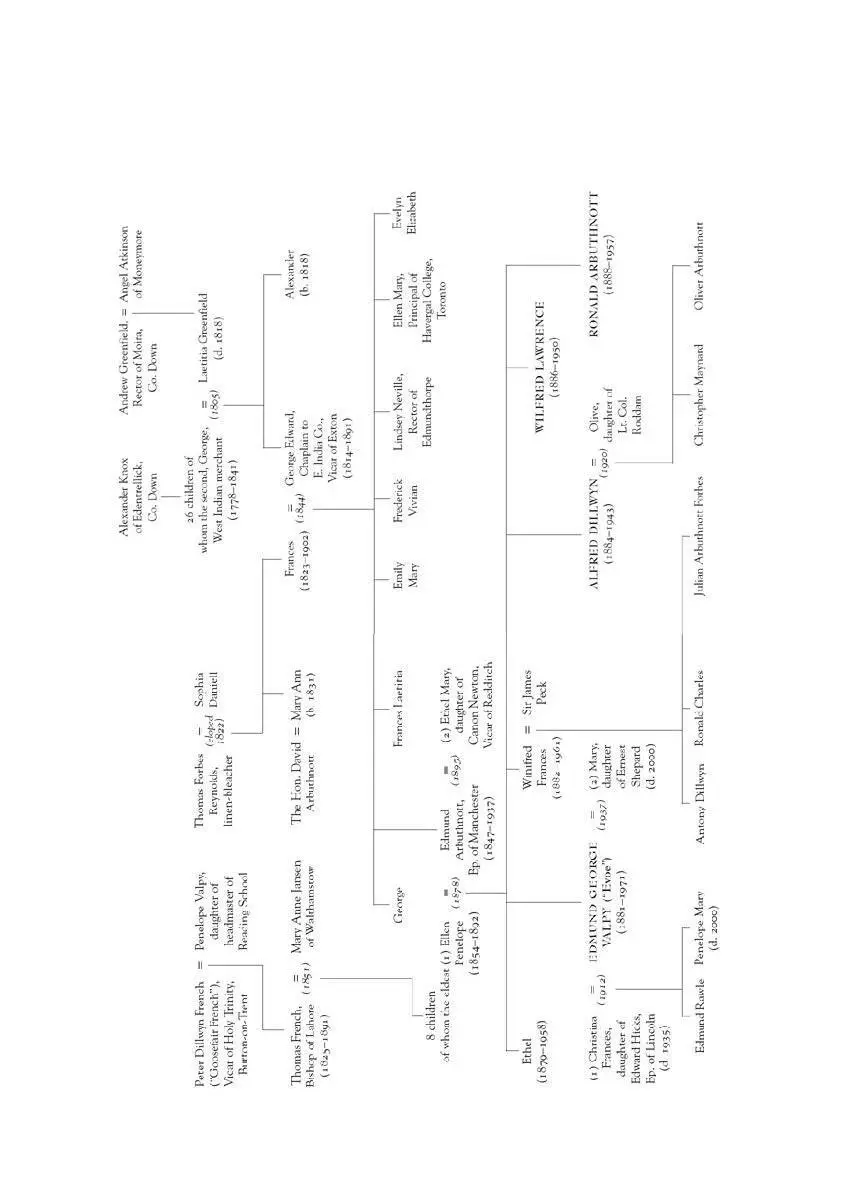

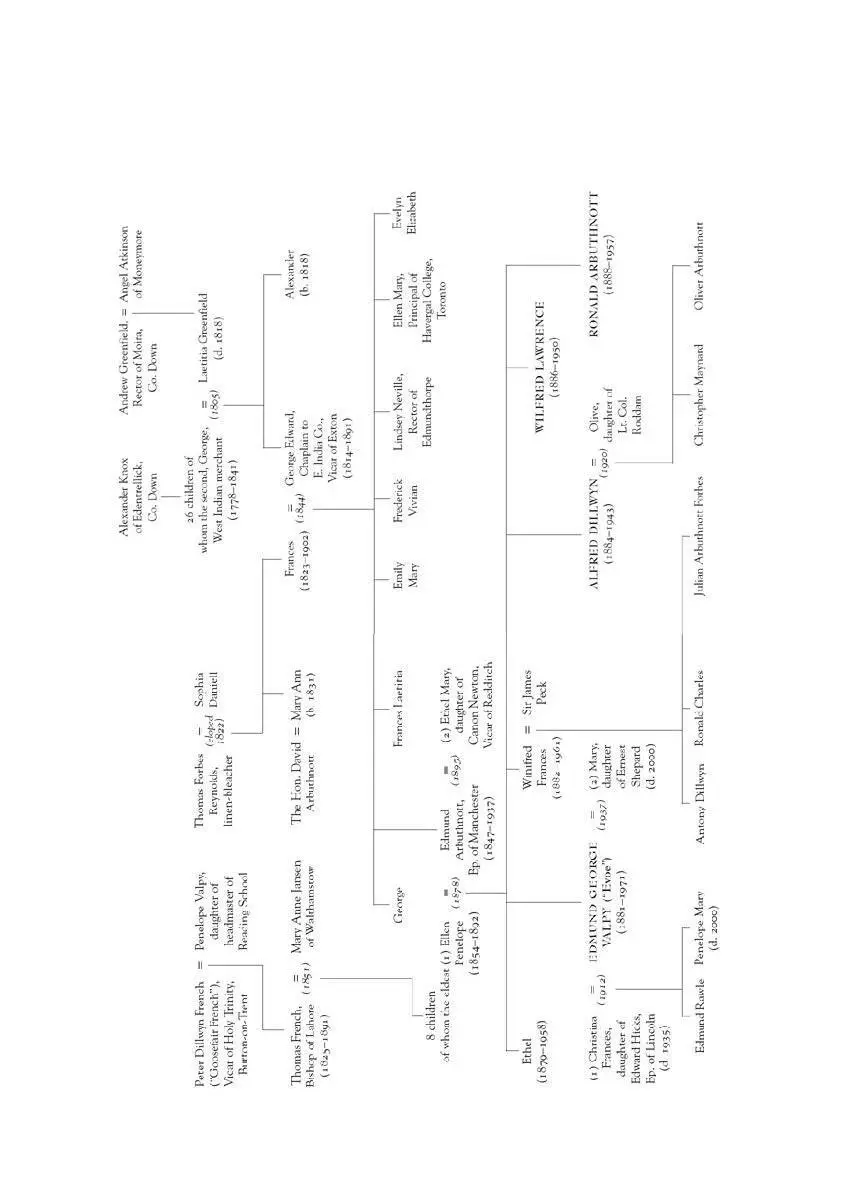

Dedication Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Genealogy Introduction by Richard Holmes Foreword I. Beginnings II. The Sterner Realities of Life 1891–1901 III. “We imagined other people might think we were peculiar” 1901–1907 IV. Knoxes and Brother 1907–1914 V. Brothers at War 1914–1918 VI. The Twenties 1919–1929 VII. “The Fascination of What’s Difficult” 1930–1938 VIII. The Uses of Intelligence 1939–1945 IX. Endings 1945–1971 Bibliography Index About the Author Also by the Author Copyright About the Publisher

For My Father

“Evoe”

OF PUNCH

Cover

Title Page PENELOPE FITZGERALD The Knox Brothers with an introduction by Richard Holmes Edmund 1881–1971 Dillwyn 1884–1943 Wilfred 1886–1950 Ronald 1888–1957

Dedication Dedication Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Genealogy Introduction by Richard Holmes Foreword I. Beginnings II. The Sterner Realities of Life 1891–1901 III. “We imagined other people might think we were peculiar” 1901–1907 IV. Knoxes and Brother 1907–1914 V. Brothers at War 1914–1918 VI. The Twenties 1919–1929 VII. “The Fascination of What’s Difficult” 1930–1938 VIII. The Uses of Intelligence 1939–1945 IX. Endings 1945–1971 Bibliography Index About the Author Also by the Author Copyright About the Publisher For My Father “Evoe” OF PUNCH

Genealogy Genealogy

Introduction by Richard Holmes

Foreword

I. Beginnings

II. The Sterner Realities of Life 1891–1901

III. “We imagined other people might think we were peculiar” 1901–1907

IV. Knoxes and Brother 1907–1914

V. Brothers at War 1914–1918

VI. The Twenties 1919–1929

VII. “The Fascination of What’s Difficult” 1930–1938

VIII. The Uses of Intelligence 1939–1945

IX. Endings 1945–1971

Bibliography

Index

About the Author

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction by Richard Holmes

PENELOPE FITZGERALD’S MARRIED NAME, the name under which she became loved and celebrated as a novelist, subtly disguised her true inheritance. For Fitzgerald was really a Knox, and this marked her invisibly – or perhaps, indelibly – all her long life, and especially in her later and astonishingly creative years.

As a Knox, she was descended from one of the great intellectual, Anglo-Catholic clans of late Victorian England. She was born Penelope Mary Knox in December 1916. Her great-grandfather had been the missionary Bishop of Lahore; her grandfather was Bishop of Manchester; one uncle was the writer and translator of the Bible Monsignor Ronald Knox (like Newman, a Roman Catholic convert); and her father was for sixteen years the much-admired editor of Punch , at a perilous time (1932–1948) when the magazine was still a great institution of national identity, like The Times or Speaker’s Corner or Harrods (and shared some of the attributes of each).

The Knox Brothers is her remarkable tribute to this family inheritance. It is a strikingly original group biography, and a highly engaging piece of family history, written with extraordinary wit and shrewdness: a funny, tender, clever book. But it is very much more than that. One might call it a study in a vanished civilization, and I am sure that it is destined to become a twentieth-century classic.

Its place in Penelope Fitzgerald’s work is intriguing. The biography first appeared in 1977, when she was sixty. But because of her unusual, late-flowering literary career, it was in fact one of her earliest books, and seems intimately connected with her self-discovery as a writer. In taking the measure of her formidable family background (and this is hardly a work of pious memorial), Penelope Fitzgerald found a narrative style, a fascination with human character, and a series of moral preoccupations which seemed to release the whole flow of her fiction.

Her late start as a novelist was something Penelope Fitzgerald was frequently, and often wistfully, quizzed about – for instance at the Hay-on-Wye Festival of 1994. She was famous for the modesty of her replies, and one explanation was that she had simply been too busy with life, until she happened to enter a Ghost Story competition organized by The Times in Christmas 1974, when she had just turned fifty-eight.

(Her winning story, ‘The Axe’ was published in The Times Anthology of Ghost Stories in 1975, and subsequently collected posthumously in The Means of Escape. Its victim, an ancient and – one might say – an almost disembodied office clerk called Singlebury, is introduced with a gentle but slightly unnerving irony, that is already recognisably hers. ‘Singlebury had, however, one distinguishing feature, very light blue eyes, with a defensive expression, as though apologizing for something which he felt guilty about, but could not put right. The fact is that he was getting old. Getting old is, of course, a crime of which we grow more guilty every day.’)

More searching interviews (such as that by Hermione Lee, for BBC Radio 3, in 1997) revealed how directly her first novels drew on a mass of autobiographical material, stored up over forty years, and awaiting a moment of release. The pattern of her life suggested a long, slow period of imaginative and intellectual assimilation, in preparation for a literary career that she had always hoped for, but never quite expected.

Tantalizing glimpses of her as a teenager appear in later chapters of The Knox Brothers. But, characteristically, she always refers to herself in the third person, as ‘the niece’ or ‘the daughter’. If you blink, you will miss them. From these we learn that she was largely brought up in literary London, in Hampstead and Regent’s Park, with an elder brother, and her father’s circle of brilliant acquaintances such as Belloc and AP Herbert. She attended (unhappily, one gathers) Wycombe Abbey, near Oxford, one of the most academically demanding of public schools for girls. This too appears in a wonderful, single-paragraph cameo in chapter seven.

In 1935, when she was still only eighteen, her mother died of cancer, which devastated the household. She writes characteristically of her father, Edmund Knox, at this time of overwhelming grief. ‘It was many years before Eddie could bring himself to mention her name directly, even to his own son and daughter. At the time, he asked the proprietors of Punch for a short leave of absence, and an understanding that he would not be writing any funny pieces for the paper that year.’ She says not a word of her own (‘the daughter’s’) feelings, but only notes that her uncle Ronald, when attending the Anglican funeral, being a Catholic insisted on kneeling alone in the aisle. (p. 208)

Penelope Knox took a First at Somerville College, Oxford. She then worked in a series of institutions, great and small (the wartime BBC, a children’s drama school, a Suffolk bookshop) having married Desmond Fitzgerald, a lawyer, in 1941. The family was mildly bohemian, in the Knox tradition, and were happy to live on a Thames barge, while taking occasional summer holidays in Italy and one memorable winter holiday in Russia. All of these experiences appear, transformed but recognisable, as settings for her later novels.

Читать дальше