For Dickens, the balloon basket and the public scaffold seemed intimately, even vertiginously, linked. They both hold out the idea of humiliation, exposure and death: the horrific promise of a fatal fall. The novelty ascents arranged by Green and others – the man on a horse, the woman on a bull (surely a Dickens invention?) – make this even worse by trivialising the terror. Worst of all is the lone ‘tumbler’, hanging over the abyss ‘chiefly by his toes’.

And here perhaps lies a possible explanation. It is with this solitary acrobat, totally exposed above the crowd, that Dickens the solitary writer surely identifies. Both ballooning and writing are ‘dangerous exhibitions’. The writer, like the balloonist, hopes to be ‘triumphant’ in front of his audience, the ‘public of great faith’. But he – or she – may fail, ‘vanquished’ despite all their skill, and drop to their long death as from a scaffold. Ballooning haunted Dickens because it reminded him of the permanent, secret terror of successful writing, the ultimate exposure of the popular entertainer, and the public fall from grace.

It is no coincidence that Dickens also slipped a balloon, almost unnoticed, into the famous, grim opening of Bleak House (1853). He wrote: ‘Fog in the Essex marshes, fog on the Kentish heights … Fog in the eyes and throats of ancient Greenwich pensioners … Chance people on the bridges peering over the parapets, into a nether sky of fog, with fog all round them as if they were up in a balloon and hanging in misty clouds .’ Here the balloon has become again an image of helplessness and doom. The very word ‘hanging’ has an uneasy echo of Dickens’ scaffold nightmare.

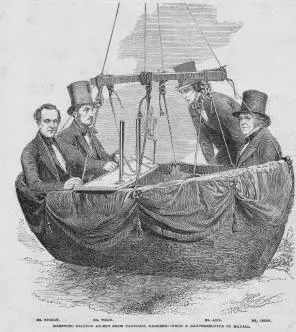

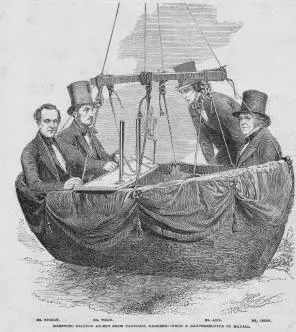

But usually the Victorian balloon had far more progressive associations. Scientific ascents also took place from Vauxhall Gardens, manned by serious gentlemen in top hats, prepared to observe and measure and speculate.

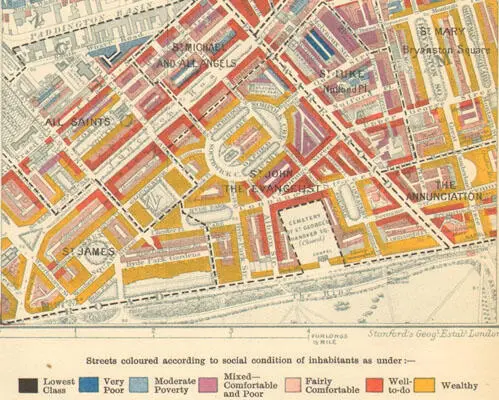

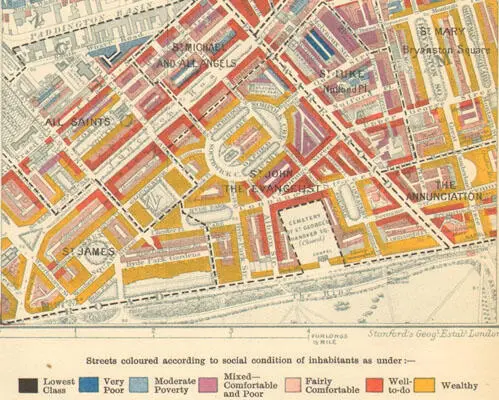

The use of the aerial panorama was even encouraged as a tool of sociological investigation. By studying the city from above, with the objective ‘angel’s eye’, it was possible to reveal much about its social structure, its balance of commercial and private dwellings, and especially (as both Poole and Mayhew had remarked) its savage contrasts of rich and poor. One indirect result of this was the famous ‘poverty maps’ compiled by the philanthropist Charles Booth in the 1880s.

These, with their colour codings and careful urban annotations, adapted the balloon overview as a technical device for compiling and storing new kinds of information. Here the ‘angel’s eye’ has become both analytical and philanthropic. The balloon perspective has become an expression of the Victorian social conscience. The ‘panoptic’ view leads potentially to both planning and improvement. It is ‘godlike’ in a new, secular way. It is an instrument of social justice, even moral redemption.

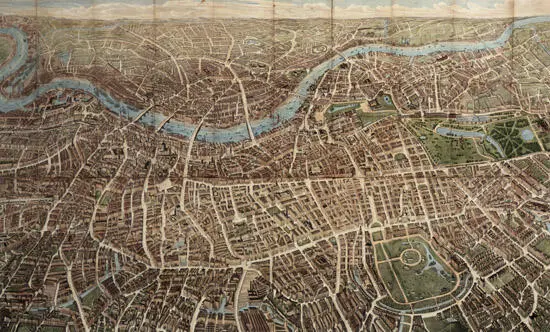

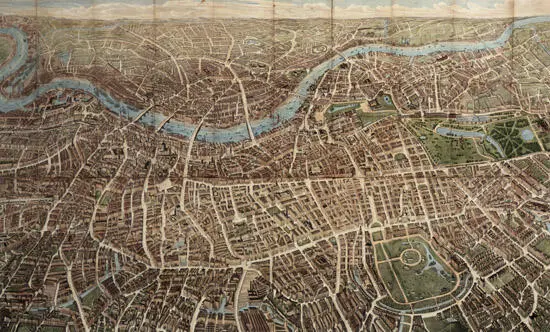

Another, more commercial, use of the panoramic ‘airborne’ view was to develop a new kind of tourist’s or visitor’s guide to the great cities. These were particularly successful with the main landmarks and thoroughfares of London and Paris. They invited the newcomer to overfly the great metropolis in imagination, to float calmly above its streets and squares, and to link one district with another. Thus journeys could be planned in a new way, and the visitor could achieve a new kind of ‘orientation’. They may even have helped people to think about the layout of big cities in a different way, no longer as a series of fixed localities or distinct villages, but as a flowing, dynamic urban environment actively linked by a moving network of cabs, horse-drawn omnibuses and trams; and later by underground railways and motor cars. Indeed, the first section of the London Underground (part of the Metropolitan and City Line) opened as early as 1863.

Panoramic, fold-out maps began to be published in the 1850s and 1860s, forerunners of the famous A to Z guides. One of the most successful was published by Appleyard & Hetling in 1854, ‘In a Case for the Pocket’, priced one shilling and sixpence. It was comprehensively entitled A Balloon View of London Taken by Daguerreotype Process, Exhibiting Eight Square Miles, Showing all Railway Stations, Public Buildings, Parks, Palaces, Squares, Streets etc … Forming a Complete Street Guide . 7In fact the ‘daguerreotype’ claim was certainly misleading, as there is no record of a genuine aerial photograph of a city before 1858–59 (Paris and Boston were to be the first). But the combination of balloon and photography evidently had a fashionable, up-to-the-minute appeal.

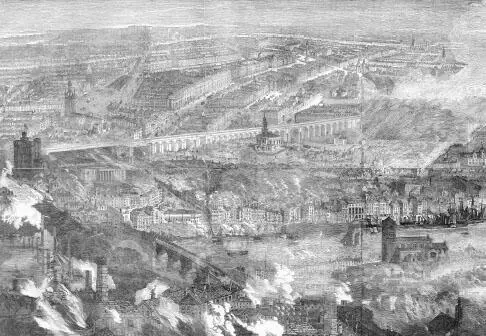

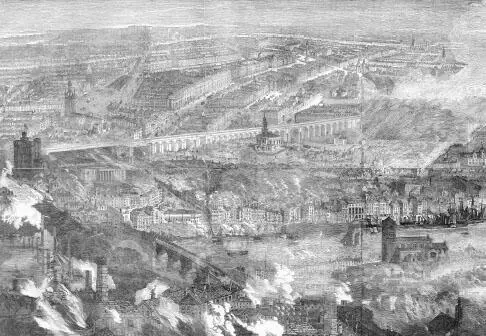

The ‘angel’s eye’ might also be used to celebrate or commemorate particular events. One of the most memorable of these was the airborne view of the Great Fire of Newcastle, which broke out at one o’clock in the morning of 6 October 1854. Starting with a horrific explosion in a chemical warehouse in Gateshead containing hundreds of tons of sulphur, naphtha, brimstone, and arsenic, the flames leaped across the river Tyne into Newcastle and burned for two days, causing over a million pounds’ worth of damage, and terrible loss of life.

An image of this catastrophe was presented by the Illustrated London News on 14 October, like an action photograph taken from a balloon. From an imaginary viewpoint some five hundred feet above Gateshead, it gives a startling panorama of houses, bridges, churches, quaysides, ships and factories, looking across the Tyne towards the great railway viaduct running through the centre of Newcastle. The pale autumnal tone of the print, predominately blue and white, is clearly the wan, aching light of dawn. But the picture is also realistically coloured and animated with leaping flames, wind-torn smoke and tiny fleeing figures, as if it was being observed in real time. (To the modern observer there is an unmistakable resonance with the hurrying, peopled cityscapes of L.S. Lowry.) It achieves a kind of mythic quality, a vision of the industrial city devoured by fire, the icon of a modern secular version of hell. Or perhaps more accurately ‘cleansed’ by fire, and thereby becoming a kind of purgatory.

The picture was published above a vivid piece of reportage, which itself achieved the extraordinary effect of an all-seeing eye.

The streets in the neighbourhood of the explosion presented a most melancholy spectacle. Men, women, and children in their night dresses might be seen rushing from their abodes in search of shelter, they knew not whither. In Gateshead particularly the scene was most distressing – mothers were vainly trying to return for a child, forgotten in the suddenness of escape – and children were searching for their parents. The quay on the Newcastle side of the river was literally strewed with burning staves and rafters, covered with sulphur, and burning like matches. Adults and children, confused by the awful catastrophe, went staggering to and fro as if intoxicated, uttering lamentable and piercing cries. At one time the whole town seemed to be devoted to the rampant agency of fire … The shop fronts and windows upon the Quayside, the Sandhill, the Side, and all the neighbouring streets, were almost universally blown out, and the gas lights, for a square mile around the spot, were extinguished in a moment, adding a weird and horrible confusion to the scene. The streets rapidly filled with the entire population of the lower parts of Newcastle, hundreds of them in their night clothes, and seriously injured. The blood-begrimed countenances of many, and the shrieks, wailing, and lamentations to be heard on every side, commingling with the voices of others devoutly calling upon the Lord to have mercy upon them, made up a scene which has been seldom paralleled. 8

Читать дальше