The structure of plants can be an issue where the cultivars presented in garden centres and plant catalogues are divergent from native forms. For example, the ‘double cultivars’ of certain flower forms, which prove popular with gardeners because of their extended flowering season and novel appearance, are less suitable for nectar-feeding insects and they also set less seed. If flower selection and form reduces opportunities for invertebrates within the garden, then it will also reduce opportunities for insect-eating birds. One consequence of this can be seen in the generally lower productivity of tit species within the urban environment. Great Tits and Blue Tits feed their young on small caterpillars and appear to struggle to find enough of these in many urban and suburban gardens (Cowie & Hinsley, 1987).

FIG 24. The larvae of craneflies and other soil-dwelling invertebrates taken from garden lawns are important for Starlings and other species. (Jill Pakenham)

It is also important to recognise the widespread use of insecticides and related compounds in gardens, since these have the potential to both reduce prey availability and to enter the food chain, where problems may then occur. More widely within the built environment there is the risk from pollution, such as with heavy metals (see Chapter 4

), which can also impact on the availability of invertebrates and alter the composition of the prey communities available to foraging birds (Eeva et al., 2005).

Fruits, seeds and nectar

Garden plants can also provide food for visiting birds more directly, through their fruits and seeds; in fact, many plants rely on birds to act as dispersal agents for their seeds, offering a nutritious fleshy fruit to attract the bird to take the seed. For example, the natural foods taken by garden-wintering Blackcaps include the berries of Cotoneaster, Honeysuckle Lonicera, Holly Ilex aquifolium, Mistletoe Viscum album and Sea-buckthorn Hippophae rhamnoides. Blackcaps have also been reported feeding on the seeds of Daisy Bush Brachyglottis greyi (Hardy, 1978). The different fruits and seeds become available at different times of the year, though predominantly from October through to January, and this can alter the shape of the bird community visiting gardens. The movement into gardens of wintering Redwing, Fieldfare and Waxwing may reflect the availability of favoured berries in gardens and their scarcity elsewhere. It has been noted, for example, that the timing of hedgerow cutting within the UK’s arable landscapes may remove large quantities of the berry standing crop from the wider landscape, leaving gardens as an important resource (Croxton & Sparks, 2004).

Some of these berries are favoured over others and in some cases a long fruiting season, such as in Holly, can suggest that the berry isn’t particularly favoured by visiting birds, only being eaten once other options are no longer available. In addition to the differences seen between different plant species, the nutritional characteristics of individual fruits may also vary with season. In many berries, the water content of the pulp decreases as the season progresses, while the average lipid content increases. Berry colour may be used as a signal, alerting berry-eating birds to the reward on offer, and there is evidence that birds may select fruits of a particular colour because of their nutritional value. Some bird species appear to select fruits with a high anthocyanin content; anthocyanin is an antioxidant and berries rich in this pigment tend to be black in colour or ultraviolet reflecting. Work on Blackcaps indicates that individuals actively select for anthocyanins in their diet and that they use fruit colour as an honest signal of anthocyanin rewards when foraging (Schaefer et al., 2007).

The consequences of the variation seen in fruits leads to species-specific preferences within the bird species that feed upon them. A series of studies by David and Barbara Snow has highlighted some of these preferences. Mistle Thrush, for example, was found to favour sloes over haws, while the preference was reversed in both Redwing and Fieldfare. Song Thrush Turdus philomelos showed a clear preference for Yew Taxus baccata, Elder Sambucus nigra and Guelder Rose Viburnum opulus, and the apparent avoidance of rosehips, while Blackbird was found to be fairly catholic in its tastes (Snow & Snow, 1988). Blackcaps make use of smaller berries in gardens, such as those of Cotoneaster conspicua (Fitzpatrick, 1996a), reflecting their almost entirely frugivorous diet (when fruit is available) within the Mediterranean wintering area (Jordano & Herrera, 1981), although it is interesting to note the importance of supplementary foods presented at garden feeding stations highlighted by Plummer et al. (2015) and explored later in this chapter.

FIG 25. Berry-producing garden shrubs can be very popular with Mistle Thrushes and other visiting thrushes, together with Blackcaps and Waxwings. (John Harding)

The presence of non-native berry-producing shrubs in gardens, while potentially a valuable food resource for visiting birds, brings with it a possible conservation issue. Since birds are the main dispersal agent for the seeds held within berries, they are a potential route by which non-native species may become more widely established within the wider countryside (Greenberg & Walter, 2010).

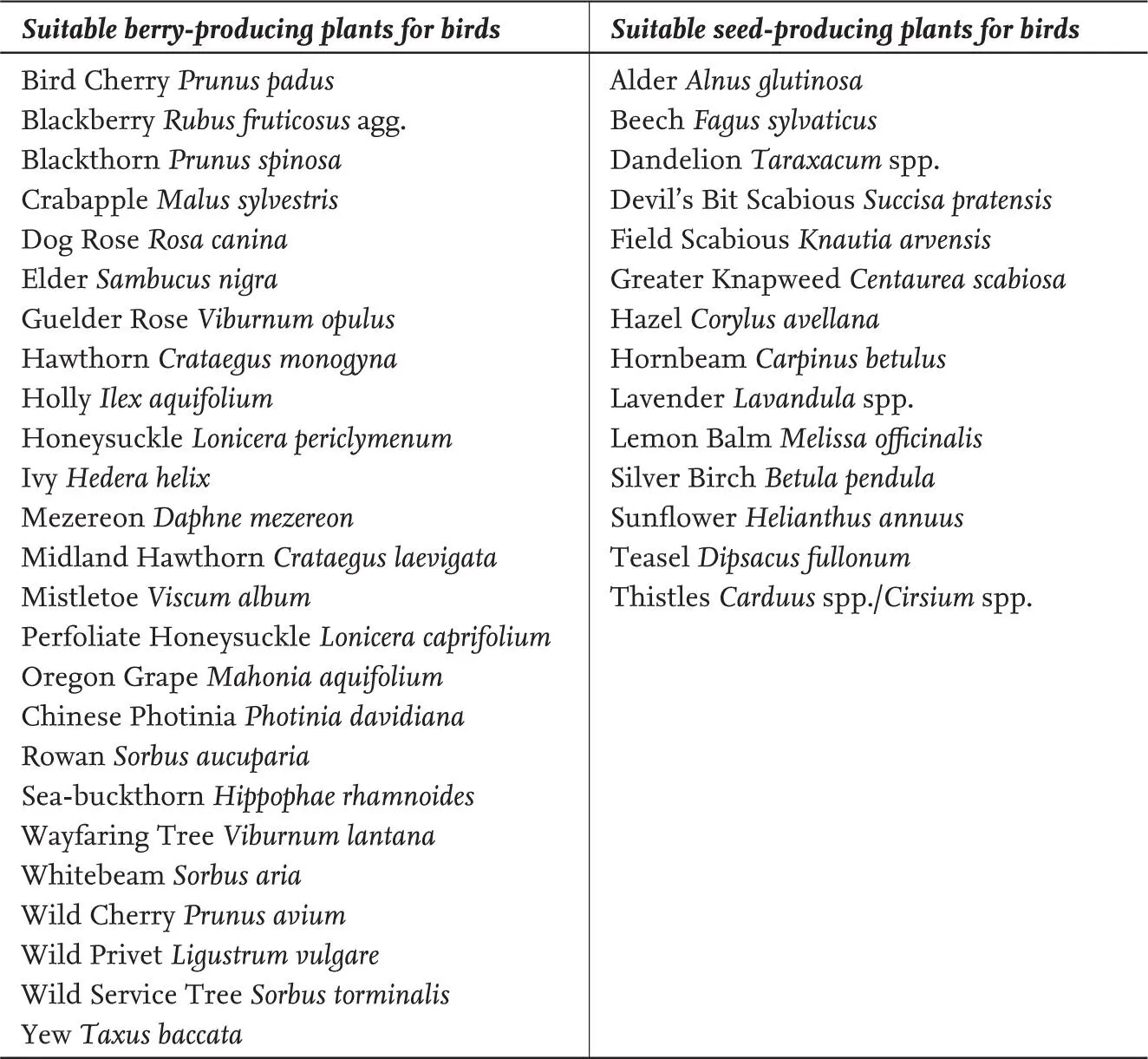

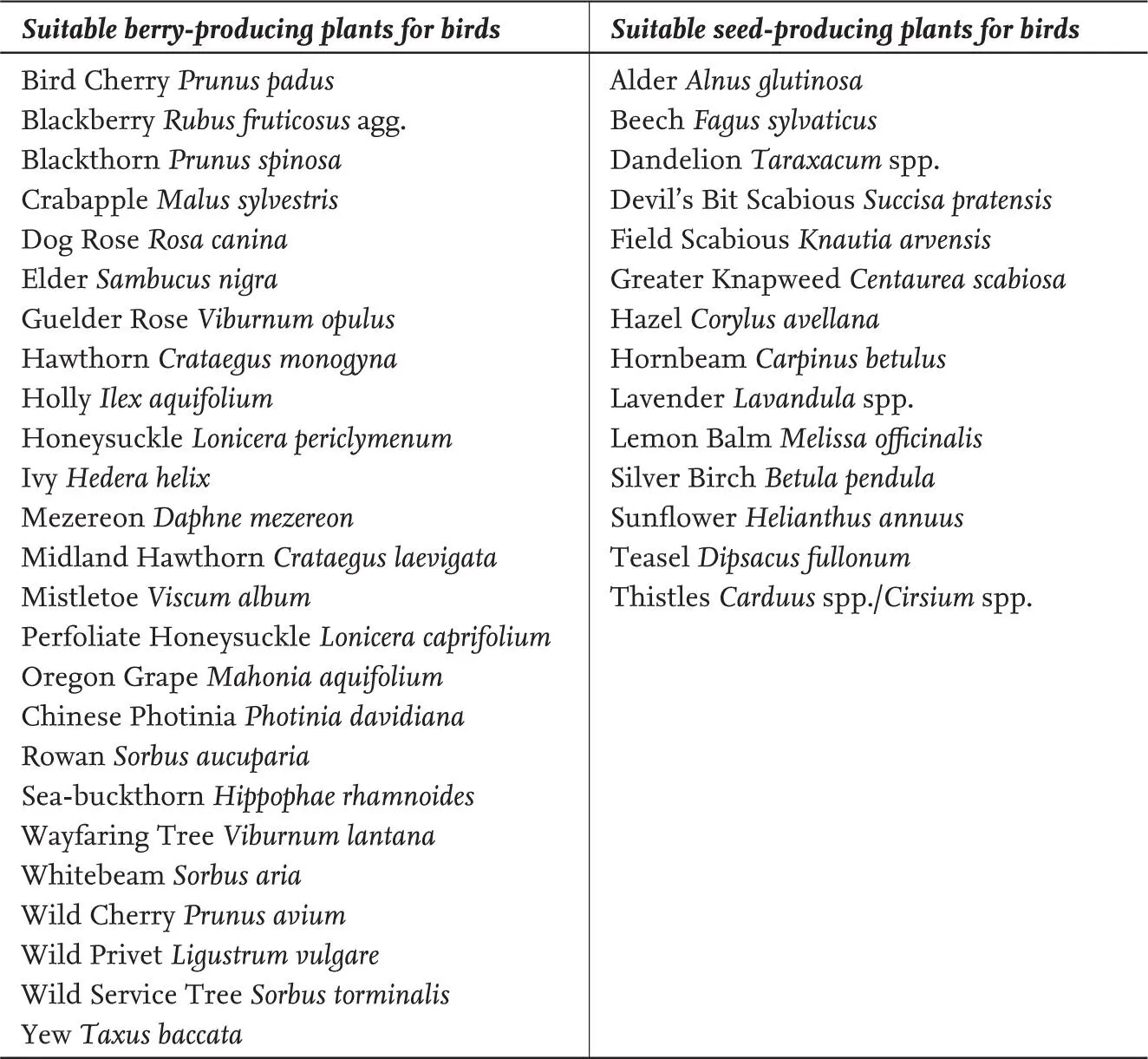

It is not just the berries that birds seek; some, such as Greenfinch, are after the seeds themselves. This can prompt plants to incorporate toxic compounds into the seed coat or its lining. Although it is the absence within the wider countryside of the seeds of larger shrubs and trees that can drive birds to garden feeding stations (see later in this chapter), it is important to note that some of our garden birds specialise in the seeds of smaller plants. The Goldfinch, for example, specialises in seeds of the Compositae family, particularly the thistles and dandelions and it is this habit that probably first brought them into gardens to feed on ornamental thistles, teasel, lavender and cornflower (Glue, 1996). Maddock (1988) reports how, from the winter of 1983/84, a few Goldfinches would visit a suburban Oxfordshire garden to feed on lavender and dry teasel heads. Their interest was maintained by brushing the teasel heads with Niger. Over the following winter, up to two dozen Goldfinches again visited the teasel head before turning to a mix of Niger, canary seed and millet provided at a garden feeding station. Important berry- and seed-producing plants for birds are shown in Table 4.

TABLE 4. Suitable plants for providing berries and seeds for garden birds. Adapted from Toms et al., (2008).

On occasion, garden birds have been reported stealing nectar from flowering plants, the latter typically exotic species whose flowers show features used to attract birds as pollinators (Búrquez, 1989; Proctor et al., 1996). Reports from within the UK have included Blue Tit – feeding from Crown Imperial Fritillaria imperialis (Thompson et al., 1996); Blackcap – feeding from Mahonia (Harrup, 1998); and Blackcap feeding from Kniphofia. In addition, the behaviour is widely recognised in a number of the warbler species migrating through the Mediterranean region (Cecere et al., 2011). Nectar feeding has also been recorded for a number of European plants (see the review by Ford, 1985), including those in the genera Rhamnus, Ferula, Acer, Crataegus, Ribes and Salix.

Читать дальше