i) suet should be derived from animals that have received ante- and post-mortem examination by veterinary officers and found to be fit for human consumption;

ii) all suet should be processed at a fully licensed and approved EU or US abattoir, and

iii) any suet products that are blended with peanuts, either in whole or granular form, must use peanuts that contain a nil detectable aflatoxin level.

Live foods

The term ‘live foods’ refers to the provision of insects, typically mealworms and wax worms, which are bred specifically for this and the wider pet food market. These may be provided alive or, more commonly, in a desiccated form. Mealworms are not worms but larvae of darkling beetles belonging to the genus Tenebrio. Within the UK it is the larvae of the Yellow Mealworm Tenebrio molitor that are most commonly used as food for wild and aviary birds, captive reptiles and amphibians. The smaller sized larvae of the Dark Mealworm Tenebrio obscura are sometimes used. As their name suggests, mealworms have a long association with human beings, occurring as pests of grain and other cereal products. Mealworms are fairly easy to rear, both at home and commercially, and a number of companies are now involved in the large-scale farming of these beetles, producing insect protein not just for wild birds and the pets already mentioned but also as a contribution to cat and dog food products and, looking to the future, human foods (Grau et al., 2017).

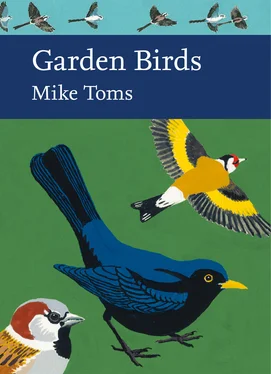

FIG 21. Mealworms are often very popular with Starlings, Robins and Blackbirds, with individual birds quickly learning to exploit them where they are offered. (John Harding)

Wild birds seem to prefer live mealworms, presumably because they attract attention by their movements, but probably because they are far closer in their composition to wild caught food. Mealworms have a high protein (13–22 per cent) and fat (9–20 per cent) content and are also a source of polyunsaturated fatty acids, essential amino acids and zinc. Perhaps surprisingly, they have a significantly higher nutritional value than either beef or chicken.

Other foods

Bread appears to be a popular food with householders, perhaps because it provides an opportunity for them to direct unwanted crusts or stale slices towards other creatures perceived to be in need of sustenance. Its nutritional value is, in the context of garden birds, unclear. Bread was by far the commonest food provided by householders who responded to a questionnaire survey carried out in Cardiff in the 1980s (Cowie & Hinsley, 1988a), with c. 90 per cent of respondents provisioning bread in both winter and summer. Galbraith et al. (2014) found bread to be the most commonly provisioned food in their study, estimating that the equivalent of more than five million loaves was put out by New Zealand residents annually.

FIG 22. A small number of UK householders put out meat scraps or even whole carcasses for visiting Red Kites. (Jill Pakenham)

Apart from the small number of householders nationally who provide meat for visiting Red Kites Milvus milvus, only a small proportion of the kitchen scraps fed to wild birds here in the UK include meat. The situation is very different in Australia where the provision of meat is fairly typical. This reflects clear differences between the main groups of birds visiting garden feeding stations here in the UK (seed-eating species) and in Australia (omnivorous species, such as Laughing Kookabura Dacelo novaeguineae, Australian Magpie Gymnorhina tibicen and Grey Butcherbird Cracticus torquatus). As we’ll see later in this chapter, the provision of meat has potential implications for wild bird health.

In parts of North America, sugar solution is used to attract and feed hummingbirds. Typically made from one-part cane sugar to four-parts water, the solution is seen as a supplementary food rather than a replacement for the sugars that these tiny birds would normally secure from flowers. While those hummingbirds tested appear to be more strongly influenced by the position of a food source rather than its colour, many feeders are red in colour because this is perceived as increasing their attractiveness to hummingbirds. Once a food source has been identified, colour may act as an important discriminator stimulus and it may be that individuals learn to associate this colour with these new nectaring opportunities (Miller & Miller, 1971). The increasing use of hummingbird feeders has been linked to the changes in the range of Anna’s Hummingbird Calypte anna, a species that now overwinters and presumably breeds at more northerly latitudes than it did a few decades ago. Examination of Project FeederWatch data (see Chapter 6

for more on this project) demonstrates that more participants in the large-scale study now offer sugar solution in hummingbird feeders than once did, though it is unclear whether the increase in feeder provision has driven the range expansion of this hummingbird species, or the range expansion has led to more people putting out hummingbird feeders (Greig et al., 2017).

THE NATURAL FOODS AVAILABLE WITHIN GARDENS

Invertebrates

Many of the birds making use of garden feeding stations also feed on invertebrates; for some garden birds, such as Wren, it is the insects and spiders found within the garden that are the food of choice. Because species like Wren usually ignore the food provided at bird tables and in hanging feeders, their presence in the garden can be easily overlooked. We don’t know a great deal about how the features present within gardens and across the wider urban environment shape the community of invertebrates that is found there. While there are some obvious relationships, others are masked by the complexity of the many microhabitats present and the influence of components within the wider landscape. Work carried out as part of the Biodiversity in Urban Gardens project (BUGS) underlines the difficulties in seeking to identify relationships between invertebrate abundance and particular features (Smith et al., 2006a).

The plant species growing within gardens will have a shaping influence on many of the invertebrate species present, not least because the plants provide many of the feeding opportunities that such invertebrates require. A typical garden flora will almost certainly comprise a mixture of native and non-native species, and the latter may prove unsuitable for insects because of their chemical composition or structural characteristics. Things may not be as bad as you might assume, however, since the chemistry of individual plant species tends to be fairly similar within a family and many of the non-native plants introduced into UK gardens belong to families that also contain a native component. The BUGS project revealed that of the 1,166 plant species recorded in 61 Sheffield gardens, 70 per cent were non-native; however, at the family level, just 36 per cent of the families were alien in origin (Smith et al., 2006b).

FIG 23. While some hoverfly species avoid being predated by mimicking less palatable species, other garden-visiting flies may be taken by Spotted Flycatchers and other bird species. (Mike Toms)

Despite this, there is evidence from work carried out in the suburban landscapes of southeastern Pennsylvania, US, that native planting can be better for both invertebrates and the birds that feed on them (Burghardt et al., 2008). Karin Burghardt and colleagues looked at a number of avian and lepidopteran community measures across paired suburban properties, one property in each pair being planted with entirely native plants and the other with a conventional suburban mix of natives and non-natives. The native-planted properties were found to support significantly more caterpillars and range of caterpillar species and had a significantly greater abundance, species richness and diversity of birds; they also had more breeding pairs of native bird species.

Читать дальше