As Darryl Jones notes (Jones, 2018), perhaps one of the most important events in the development of bird feeding within the UK was the 1908 publication in English of a German book on how to attract and protect wild birds. Written by Martin Hieseman, the book was based on the work of Baron Hans Freiherr von Berlepsch, a nobleman who had spent a considerable amount of time conducting ornithological experiments on his large estate. Included within the publication were several ‘appliances’ that had been developed to provide wild birds with food. Of these, the ‘food bell’ and ‘food house’ would be recognisable today; a somewhat more outlandish appliance – though you can see where the Baron was coming from – was the ‘food tree’. This was a small spruce or fir tree over which a mixture of meat, bread, poppy flour, millet, oats, elderberries and seeds, bound together with beef or mutton fat, was poured. A smaller version of this appliance – the ‘food stick’ – presumably was aimed at those with less opportunity to produce small conifers quite so readily.

FIG 18. The use of coconut shells, filled with fat or suet, is still popular with both garden birds and those who feed them. (Mike Toms)

Over the ensuing decades more publications followed, some of which proved instrumental in shifting us towards today’s pattern of year-round feeding. The growing interest in feeding wild birds was certainly being recognised as a characteristic of the UK population; a 1910 article in Punch magazine identified bird feeding as a national pastime and included a number of adverts for feeding devices. A major development in bird feeding occurred when Droll Yankees’ 1960 A-6F tubular bird feeder was produced. This device supported the delivery of seed, particularly sunflower seed, keeping it dry and secure. More recent changes have largely sought to modify the successful Droll Yankees’ design, for example by looking at the shape and positioning of the feeding ports and their associated perches.

THE TYPES OF FOODS PROVIDED

It wasn’t just the development of feeding devices that proved to be important. In the US, the Kellogg Seed Company, which had been selling birdseed since the end of the First World War, brought a seed mix – the ‘Audubon Society Mixture’ – to market, a mix that had been developed in association with the Audubon Society following a series of experiments to determine which foods were preferred by wild birds. Five years later, ‘Swoop’ Wild Bird Food appeared in the UK and soon after that came new forms of sunflower seed and the tiny black seeds of Niger Guizotia abyssinica. While the main markets for wild birdseed are in Europe and North America, the key production areas lie elsewhere, in eastern Europe (particularly important for sunflower seed), China, India and Myanmar.

The foods provided at garden feeding stations differ in their composition, both in terms of macronutrients like carbohydrate, fat and protein, and micronutrients like calcium, carotenoids and vitamin E. All are important for birds, though in differing amounts and some may be more important at particular times of the year than at others. Protein, for example, plays an important role in female birds as they prepare for the demanding production of a clutch of eggs. When you look at the foods most commonly provided at garden feeding stations here in the UK, you soon discover that they typically have a higher fat content relative to that of protein: black sunflower seeds (fat 44.4 per cent : protein 18.0 per cent), peanuts (44.5 per cent : 28.7 per cent) and peanut cake (70.5 per cent : 17.1 per cent) (Jones, 2018). In addition to their carbohydrate, protein and fat content, foods like peanuts and sunflower seeds may be important sources of micronutrients, such as vitamin E. As will become clear later in this chapter, these micronutrients are not just important for the adult bird; they are also important for eggs and their developing embryos.

Sunflower seeds and sunflower hearts

The sunflower seeds used for bird feeding have a relatively high edible oil content, something that results from several decades of work using selective breeding. The plant itself originates in North America and was initially cultivated by Native Americans, the seed probably arriving in Europe through Spain. Russian agronomists took a great deal of interest in sunflower seeds and began a programme of work selecting for those that were high in oil, successfully delivering an increase in edible oil content from 20 per cent to almost 50 per cent. These high edible oil lines from Russia were reintroduced into North America after the Second World War, rekindling interest in the crop. It is from here that sunflower seeds appear to have entered the bird food market, although eastern Europe and Russia – which account for just under half of the worldwide production – are now the most important source for sunflowers entering the UK market. Worldwide production is about 40 million tonnes.

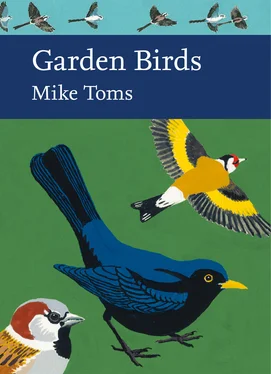

FIG 19. Sunflower hearts, with their high edible oil content, are very popular with garden birds like Goldfinch. The popularity of these seeds has as much to do with Russian agronomists as it does with American entrepreneurs. (John Harding)

Sunflower seeds and their oil have a range of market uses, with the black-husked oilseed type a staple for bird food; this was introduced into the UK in the 1970s. Sunflower hearts were first introduced to the UK market during the early 2000s, their use proving popular with both wild birds and with the people putting out food. Unlike black sunflower seeds, hearts are already de-husked so leave less mess under bird feeders that then needs to be cleaned up. The lack of a husk also reduces handling times for feeding birds, which makes the hearts energetically more attractive that the traditional black sunflower seeds. At 6,100 kcal per kg, the calorie content of sunflower hearts is better than that of peanuts (5,700 kcal per kg); because the hearts have been de-husked, by weight they are also significantly higher in kcal than black sunflower seeds (5,000 kcal per kg).

Peanuts

Peanuts, also known as monkey nuts or groundnuts, are the edible seeds of Arachis hypogaea, a cultivated leguminous plant originating from a genus that developed in southwest Brazil and northeast Paraguay, where the most ancient species in the genus still grow. Available evidence suggests that Arachis hypogaea itself emerged within the hunter/cultivator communities present in Peru and/or Argentina. Peanut shells dated to 1800–1500 BCE have been excavated from sites near Casma and Bermejo in Peru and in the High Andes of northwest Argentina. There is also evidence of early presence in China, suggesting that mariners from China visited the South American region and returned home with peanuts. Evidence from shipwreck remains off the South American coast adds further support to this hypothesis.

In recent history, and up until the 1960s, peanut production was dominated by countries within the sub-Saharan region of Africa, but this changed rapidly following low yields, change in domestic policies and a reduction in market pull (Pazderka & Emmott, 2010). Over the same period (see Table 2), China became the dominant producer of peanuts, securing 37 per cent of the producer market share by the mid-2000s and benefitting from internal agricultural reforms and the development of its market economy. Production within some countries (e.g. India and Indonesia) is more targeted towards internal markets than export and there has also been an interesting development in the market for value-added prepared peanuts, which is why the Netherlands features so prominently in the export table.

Читать дальше