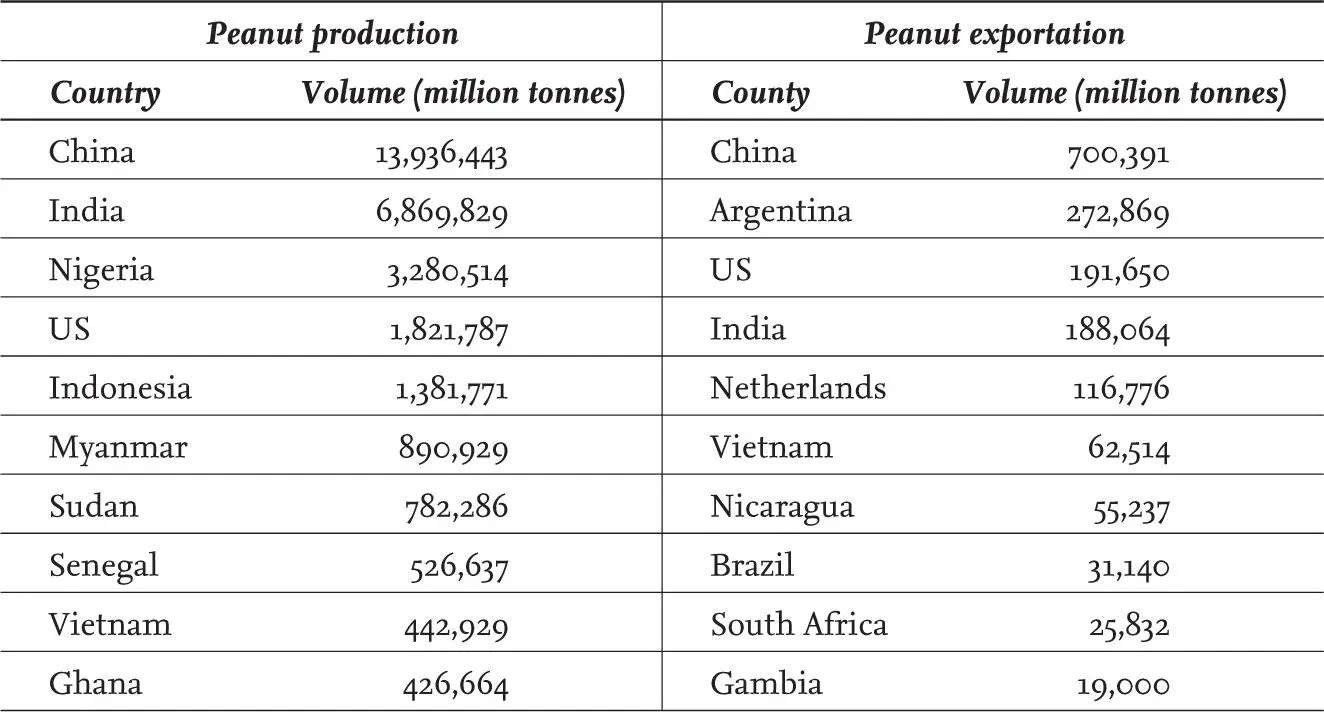

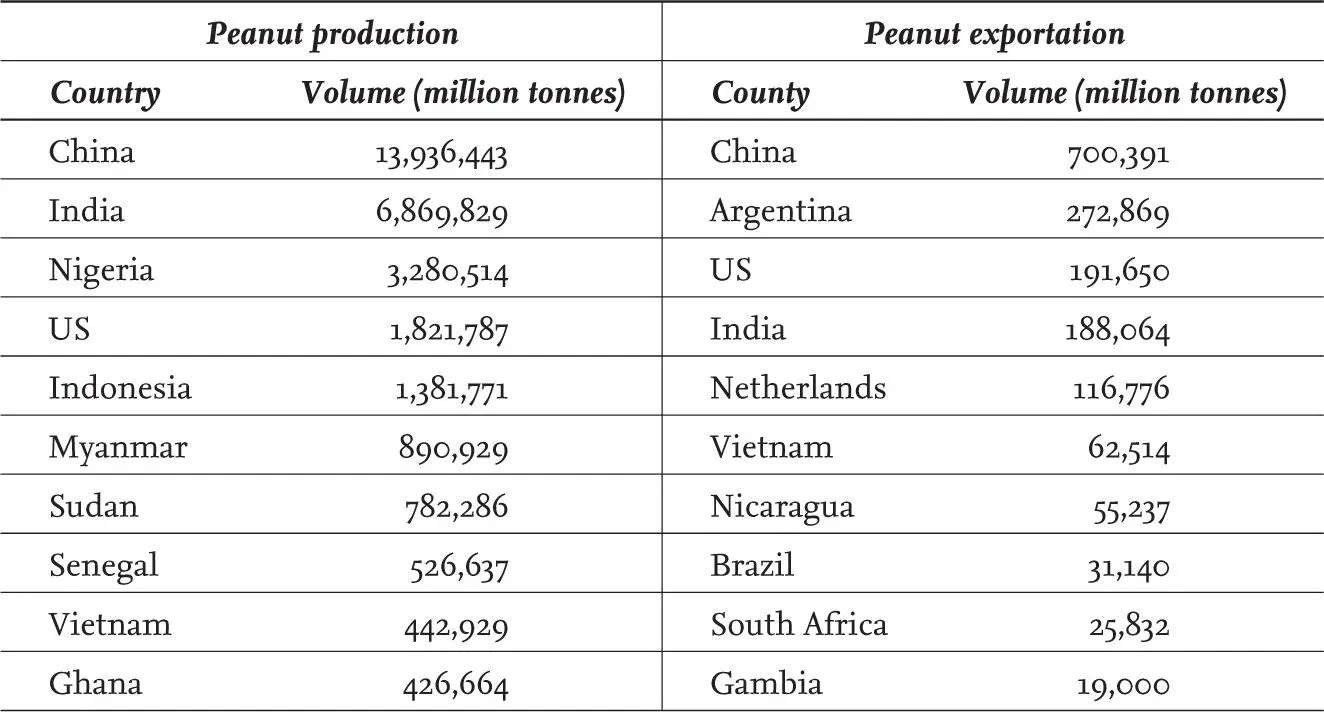

TABLE 2. Peanut production and exportation at a global scale, 2001–07. Data from Pazderka & Emmot (2010).

Peanuts can vary in their quality, both between regions and in relation to local climatic factors. There is, for example, a general acceptance that those produced in China are of better quality than those originating in India because of the higher oil content that they contain. With more than 100 countries cultivating peanuts, of many different varieties, it is easy to see how the wild bird food peanut market now has global reach. As we will discover in Chapter 4, peanuts are not without their problems; the presence of aflatoxin is a major threat to the market and to peanuts destined for wild bird food. In some years and areas, whole crops can be lost because of the presence of aflatoxin – which is toxic to both humans and birds – and this is why, for example, US producers can spend in excess of $27 million annually in order to ensure that their peanuts meet the agreed standards for aflatoxin control.

Peanuts were once a staple at UK garden feeding stations, initially presented in mesh bags, and to some extent still are for many of those who feed wild birds. However, the development of new seed mixes and the popularity of sunflower seeds and hearts with both birds and bird feeders have reduced their prominence. It is not unusual for those providing food to comment that the peanuts in their feeders often go largely untouched, except for visiting Great Spotted Woodpeckers and occasional Nuthatches Sitta europaea.

Seed mixes

A wide range of seed mixes is now available for use in feeding wild birds and these can vary greatly in their composition. In addition to seed-only mixes, some also include fat- or suet-based material or have invertebrate protein or fruit added to them. Watch a Greenfinch feeding at a feeder containing a seed mix and you’ll soon discover that the bird will typically select certain seeds and drop others. This pattern of selection reflects the fact the different seeds and grains vary in both their nutritional content and in the time required to process them. A feeding bird is seemingly able to balance these two components and make an appropriate selection.

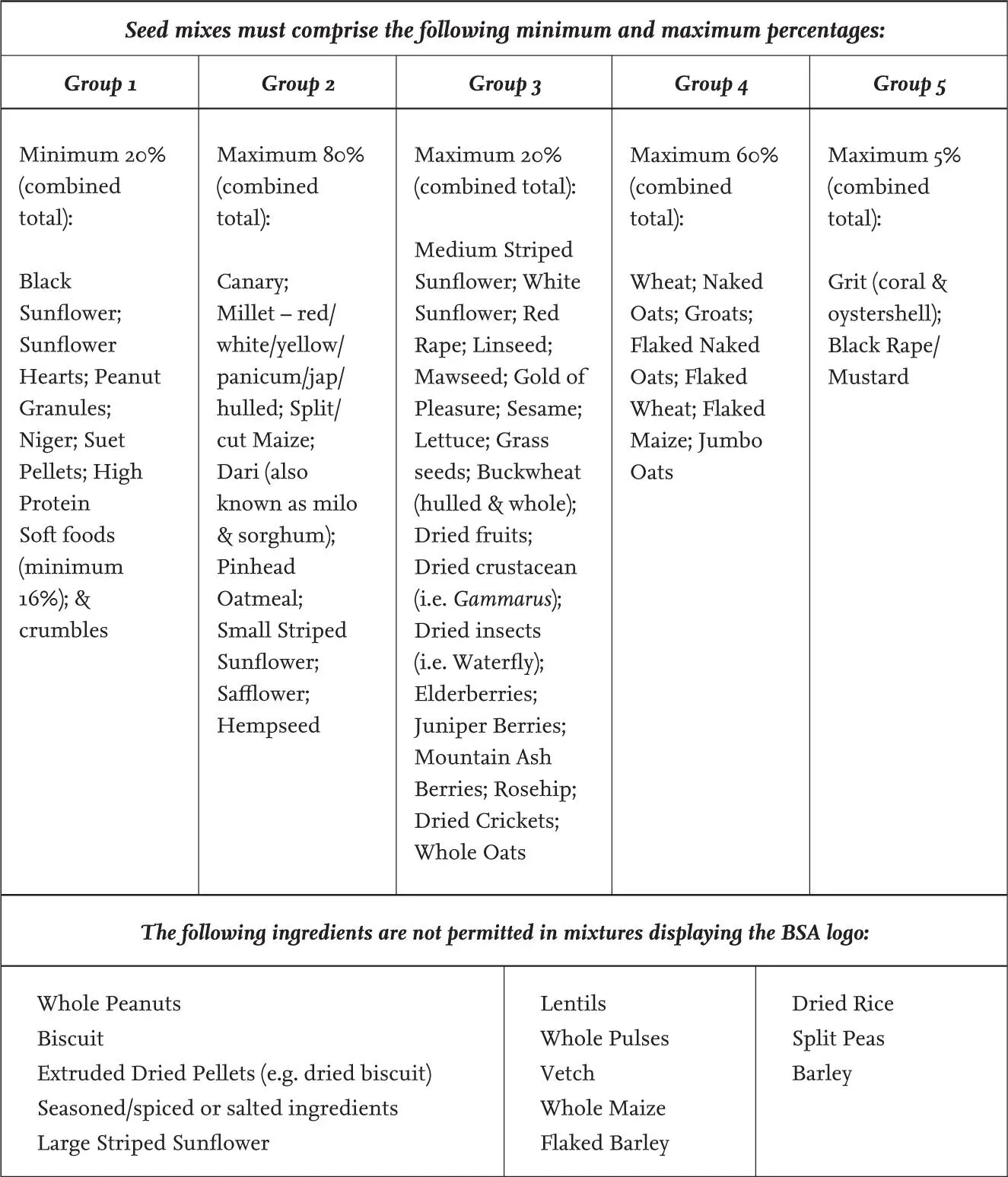

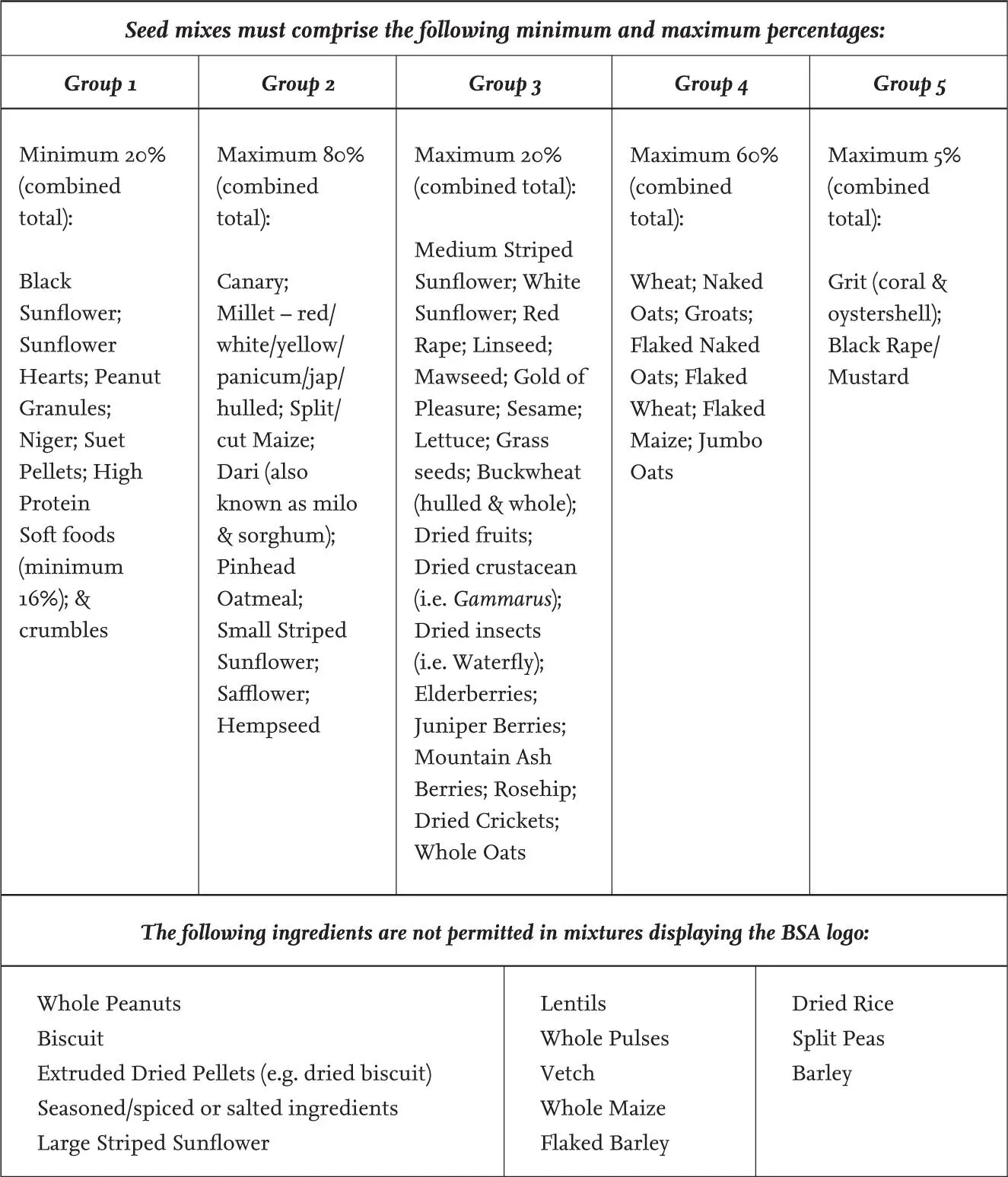

Recognising the different nutritional content of different types of seed, and wishing to secure an advantage in what is a highly competitive market, a number of wild bird care companies have signed up to the Birdcare Standards Association, an industry body that is governed by a set of guidelines. The guidelines for wild birdseed (see Table 3) effectively identify certain foodstuffs as being largely unsuitable. These, which include buckwheat and whole oats, sometimes feature prominently in cheaper seed mixes, where they effectively provide a bulking agent, which is little used by the birds. When looking for a seed mix, you often find that you get what you pay for, the better-quality mixes commanding a premium. However, you also need to consider the species that will be feeding on the mix; if, for example, the main recipients will be House Sparrows, then a mix with larger seeds and grains is likely to be better used than one which is made mostly of smaller seeds which the sparrows find difficult and time-consuming to process.

TABLE 3. The Birdcare Standards Association sets the following compulsory standards for seed mixes carrying the Birdcare Standards Association logo.

Niger

The small seeds of Niger were originally used to produce a cooking oil by peoples living within eastern Africa, and cultivation probably first occurred in the Ethiopian highlands. The seed was renamed ‘Nyjer’ in the US, in part to clarify its pronunciation and avoid unfortunate associations with a similar-looking slang word, being registered as a trademark of Wild Bird Feeding Industry, a now well-established US company, in 1998. It is sometimes referred to, incorrectly, as ‘thistle’ seed. As a flower, Niger had certainly been introduced to British gardens by 1806, and the species has been known in the wild since 1876. There is a suggestion from national botanical surveys that its occurrence in the wild is increasing, perhaps because of its use in bird food. As a commercial crop, Niger is mainly grown in India, Ethiopia and – to a lesser extent – Myanmar, underlining the global scale of production that ends up on UK garden centre shelves.

Use as a supplementary food for wild birds came rather later, the seed starting as something of a niche ‘conditioning’ product used by cage bird enthusiasts. It was known to be popular with American Goldfinch Spinus tristis and Pine Siskin Spinus pinus in the US in the 1960s, and it was the association with Goldfinches here in the UK that helped its popularity to increase. The seed’s small size leads to it being favoured by fine-billed species like Goldfinch and Siskin, with larger-billed species finding it too delicate to bother with. The small size also requires the use of a special ‘nyjer feeder’, whose small feeding ports prevent the seed from flowing out of the feeder and onto the ground – which is what happens if you inadvertently put the seed into a standard feeder. Initially, it seems that the provision of Niger seed at garden feeding stations encouraged the arrival of Goldfinches, with some participants in the BTO Garden BirdWatch scheme commenting on how they had never had visiting Goldfinches until they started provisioning the seed. Others, however, failed to attract them to Niger, even where it was provided alongside other foods at garden feeding stations. One of the interesting patterns of Niger use by Goldfinches appears to be the move away to sunflower hearts over recent years; this may be linked to the decline in UK Greenfinch populations following the emergence of finch trichomonosis (see Chapter 4

) and the release of Goldfinches from competition with this larger and more dominant species. Niger seed may still be an important food for Siskin and Lesser Redpoll Acanthis cabaret, the latter species now being seen more commonly at UK garden feeding stations.

FIG 20. With their fine bill, Siskins are one of the species to have taken to Niger seeds, though they seem to prefer sunflower hearts if these are available and there is little competition from larger species like Greenfinch. (John Harding)

Fat and suet products

Although highly variable in terms of their content, a high-quality fat product may have in excess of 8,500 kcal per kg, something that makes these products particularly attractive for use during the winter months. Fat- and suet-based products come in a diversity of forms, probably the most familiar of which are ‘fat balls’ and square or rectangular blocks. Fat balls almost always used to be sold within plastic mesh netting, something that was occasionally responsible for the death of a feeding bird, either caught by its foot or by its barbed tongue. Although a substantial number of netted fat balls are still sold (and purchased) within the UK market, there has been a welcome move towards un-netted fat balls.

Suet may also be presented in a pelletised form, something that is popular with Starlings, or in or around objects such as plastic sticks or coconut shells – popular with Blue Tits and Great Tits. Suet products often contain additional material, perhaps added to increase the range of species that will take it, to broaden its nutritional composition or to secure a marketing advantage. These include seeds, nuts, berries and insect protein (typically mealworms). Suet products may also contain ash in variable quantities, added in order to bind the material together and to reduce the chances of the product breaking down. Again, the Bird Care Standards Association has a set of rules relating to this type of product, though these are geared more towards the source of the fat, rather than the composition of the product or content of additional material. The standards are as follows:

Читать дальше