Calculating the ‘True’ Earnings of a Business

When you buy or sell a business, sooner or later you’ll hear the term EBITDA , short for Earnings Before Interest and Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation. (People sometimes talk about EBIT instead, a simpler version that means Earnings Before Interest and Tax.)

You may even hear people say things like: ‘Did you hear that Sam got five times EBITDA when he sold his business?’ What they mean is that when Sam sold his business, he received five times his average annual profit, after adjusting this profit for amortisation, depreciation, interest and tax.

Although calculating EBITDA or EBIT is kind of technical, you don’t need a degree in commerce. Here’s how the whole deal runs:

1 Ask the owners for copies of Profit & Loss statements for the last three to five years.Five years is ideal, three years is often all you get. Make sure these Profit & Loss statements are final statements certified by an accountant, and not print-outs generated by the owners themselves.

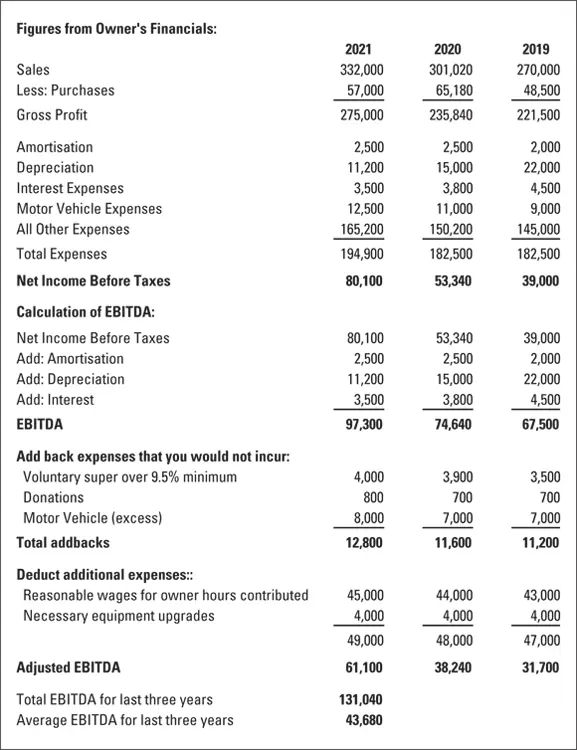

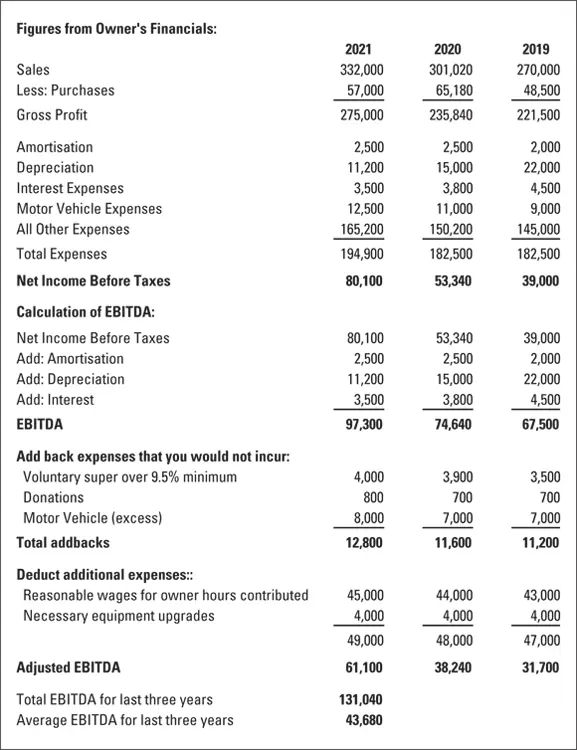

2 Go through each Profit & Loss report and summarise key totals, finishing with the final net profit (or even loss) before income tax.I recommend you use a spreadsheet, as I do in Figure 3-1. I like to include sales, cost of sales, gross profit and key expenses. If you’re working with company financials, remember to write down the net profit before income tax, not after income tax.

3 Add any amortisation, depreciation or interest back into the profit.The amount of interest paid depends on how much equity the owner has in the business. You’re best to ignore interest when calculating average net profit, so add any interest expense back onto the bottom line to increase the profit.Amortisation is a bit of an obscure one, and refers to writing off goodwill or borrowing expenses. If you can’t see this item on the Profit & Loss report, don’t worry — it probably doesn’t exist.

4 Add back any expenses that seem downright excessive.You know, things such as the single owner-operator who puts three cars through his business (one for him, one for his partner and one for the teenage child) or puts all the expenses for the latest, most expensive four-wheel drive through the business. Other likely culprits include voluntary superannuation contributions, overseas holidays or unrealistically high wages paid to relatives.Refer to Figure 3-1 for how this whole deal works.

5 If the business is a sole trader or partnership, deduct a reasonable amount for the time the owners spent working in the business.If the business is a sole trader or partnership, the Profit & Loss doesn’t include wages for the owners. Find out how many hours the owners work in the business, multiply these hours by a reasonable hourly rate (either for you or for employees), and then deduct the total from the profit. One of my clients wanted to purchase a milk bar. The figures looked good, with hefty profit year after year. Then my client figured that the owner, her husband and her son all worked in the milk bar — up to 150 hours a week combined. My client was single and didn’t want to work any more than 50 hours a week. This difference meant she had to factor in 100 hours additional employee labour every week. After she made this adjustment, the calculations for the goodwill of the milk bar came up as worthless.

6 If the business is a company, look at the wages paid to the directors and, if necessary, adjust the profit for what you think are reasonable wages for the time spent.If you think the directors’ wages were too high, add the amount of the excess to your profit figure. If you think the directors’ wages were too low, deduct the shortfall from your profit figure.

7 Deduct any additional expenses that you know you’re likely to have.One of the things that often happens when a business is for sale is that everything is a bit run-down and hasn’t been properly maintained. In the example in Figure 3-1, I add an extra $4,000 a year for the amount I think should have been paid to keep everything in reasonable condition.

8 Adjust the profit for any irregular or unusual income and expense items.Trawl through the financials. You’re looking for irregular income such as large insurance claims or capital gains, and you’re also searching for unusual expense items such as moving expenses, compensation claims or capital losses.

9 Calculate the average profit for the period you’re analysing.You know the deal. If you have three years’ worth of figures, add the final profit for each year together, and divide this total by three.

10 Note down the final value: You’ve now calculated the average Adjusted EBITDA.Now that you’ve calculated EBITDA, you’re ready to make an estimate of what the business is actually worth. Read on to find out more …

FIGURE 3-1:Calculating average profit (also known as EBIT).

Valuing an Existing Business

So, how much is a business worth? At the end of the day, a business is only worth what a buyer pays for it. Until this value is known, figuring out the real worth of a business is an odd mix of accounting, gut-feeling and the weighing up of probabilities, with a hotchpotch of possible valuation methods all offering different takes on the subject. Experienced valuers often prefer to value a business using a couple of different methods, arriving at an average of the results as their final opinion.

Businesses are a bit like children. Sellers (like any parent) can run a little short on objectivity. For this reason, do your own sums and arrive at your own opinion about how much a business is worth. However, do note that interpreting financial statements is complex, and you must always seek expert advice from your accountant before making any kind of offer to purchase a business.

Businesses are a bit like children. Sellers (like any parent) can run a little short on objectivity. For this reason, do your own sums and arrive at your own opinion about how much a business is worth. However, do note that interpreting financial statements is complex, and you must always seek expert advice from your accountant before making any kind of offer to purchase a business.

The times earnings method

When you know what the Adjusted EBITDA of a potential business is (refer to the previous section to refresh your memory on how to calculate EBITDA), you’re ready to calculate how much moolah this business opportunity is really worth.

The times earnings method is based on the idea that you multiply the Adjusted EBITDA by a times earnings multiplier to arrive at an overall valuation of goodwill. (If a business has debtors, equipment, furnishings or inventory, you add the agreed value of these assets to this goodwill figure.) Typical multipliers can range from two to six times Adjusted EBITDA. For example, if a business had an Adjusted EBITDA of $100,000 and your accountant recommends a multiplier of four, the total value of goodwill for the business would be $400,000. So, the price for the business would be $400,000, plus the value attributed to debtors, equipment, furnishings or inventory.

Although I can’t advise you as to what multiplier is typical to your industry, here are some rough-and-ready guidelines for EBIT multipliers:

Although I can’t advise you as to what multiplier is typical to your industry, here are some rough-and-ready guidelines for EBIT multipliers:

Listed companies typically sell for a higher multiplier than private companies, and can even sell for up to ten times EBIT.

If a business is suffering downwards sales trends, selling in a rush or operating without a secure lease, it may sell for as low as one or two times EBIT.

An asking price anywhere between two and six times EBIT is reasonable for a private business.

Читать дальше

Businesses are a bit like children. Sellers (like any parent) can run a little short on objectivity. For this reason, do your own sums and arrive at your own opinion about how much a business is worth. However, do note that interpreting financial statements is complex, and you must always seek expert advice from your accountant before making any kind of offer to purchase a business.

Businesses are a bit like children. Sellers (like any parent) can run a little short on objectivity. For this reason, do your own sums and arrive at your own opinion about how much a business is worth. However, do note that interpreting financial statements is complex, and you must always seek expert advice from your accountant before making any kind of offer to purchase a business. Although I can’t advise you as to what multiplier is typical to your industry, here are some rough-and-ready guidelines for EBIT multipliers:

Although I can’t advise you as to what multiplier is typical to your industry, here are some rough-and-ready guidelines for EBIT multipliers: