The interpretation of the ceremonies just mentioned, as given me, is this: The Indian was laid in his grave to remain there, it was believed, only until the fourth day. The fires at head and feet, as well as the waving of the torches, were to guard him from the approach of “evil birds” who would harm him. His feet were placed toward the east, that when he arose to go to the skies he might go straight to the sky path, which commenced at the place of the sun’s rising; that were he laid with the feet in any other direction he would not know when he rose what path to take and he would be lost in the darkness. He had with him his bow and arrow, that he might procure food on his way. The piece of burnt wood in his hand was to protect him from the “bad birds” while he was on his skyward journey. These “evil birds” are called Ta-lak-i-çlak-o. The last rite paid to the Seminole dead is at the end of four moons. At that time the relatives go to the To-hŏp-ki and cut from around it the overgrowing grass. A widow lives with disheveled hair for the first twelve moons of her widowhood.

Table of Contents

The one institution at present in which the religious beliefs of the Seminole find special expression is what is called the “Green Corn Dance.” It is the occasion for an annual purification and rejoicing. I could get no satisfactory description of the festival. No white man, so I was told, has seen it, and the only Indian I met who could in any manner speak English, made but an imperfect attempt to describe it. In fact, he seemed unwilling to talk about it. He told me, however, that as the season for holding the festival approaches the medicine men assemble and, through their ceremonies, decide when it shall take place, and, if I caught his meaning, determine also how long the dance shall continue. Others, on the contrary, told me that the dance is always continued for four days.

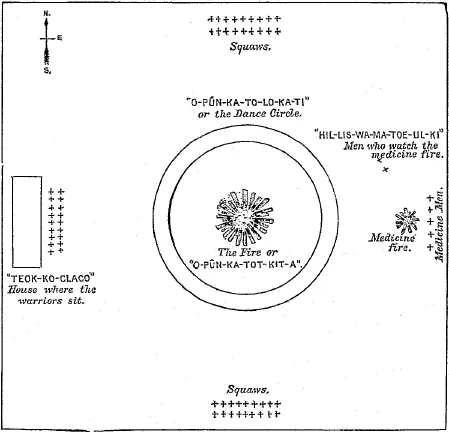

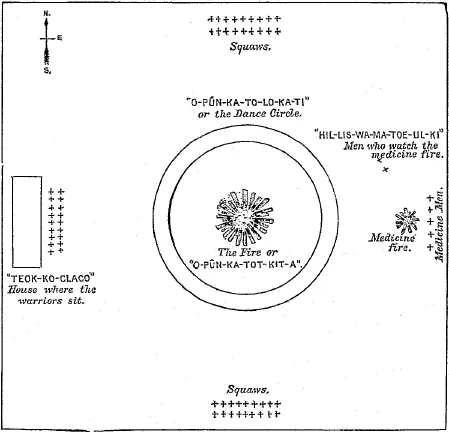

Fifteen days previous to the festival heralds are sent from the lodge of the medicine men to give notice to all the camps of the day when the dance will commence. Small sticks are thereupon hung up in each camp, representing the number of days between that date and the day of the beginning of the dance. With the passing of each day one of these sticks is thrown away. The day the last one is cast aside the families go to the appointed place. At the dancing ground they find the selected space arranged as in the accompanying diagram ( Fig. 77).

The evening of the first day the ceremony of taking the “Black Drink,” Pa-sa-is-kit-a, is endured. This drink was described to me as having both a nauseating smell and taste. It is probably a mixture similar to that used by the Creek in the last century at a like ceremony. It acts as both an emetic and a cathartic, and it is believed among the Indians that unless one drinks of it he will be sick at some time in the year, and besides that he cannot safely eat of the green corn of the feast. During the drinking the dance begins and proceeds; in it the medicine men join.

At that time the Medicine Song is sung. My Indian would not repeat this song for me. He declared that any one who sings the Medicine Song, except at the Green Corn Dance or as a medicine man, will certainly meet with some harm. That night, after the “Black Drink” has had its effect, the Indians sleep. The next morning they eat of the green corn. The day following is one of fasting, but the next day is one of great feasting, “Hom-pi-ta-çlak-o,” in which “Indian eat all time,” “Hom-pis-yak-i-ta.”

Green Corn Dance.

Table of Contents

Concerning the use by the Indians of medicine against sickness, I learned only that they are in the habit of taking various herbs for their ailments. What part incantation or sorcery plays in the healing of disease I do not know. Nor did I learn what the Indians think of the origin and effects of dreams. Me-le told me that he knows of a plant the leaves of which, eaten, will cure the bite of a rattlesnake, and that he knows also of a plant which is an antidote to the noxious effects of the poison ivy or so-called poison oak.

Table of Contents

I close this chapter by putting upon record a few general observations, as an aid to future investigation into Seminole life.

Table of Contents

The standard of value among the Florida Indians is now taken from the currency of the United States. The unit they seem to have adopted, at least at the Big Cypress Swamp settlement, is twenty-five cents, which they call “Kan-cat-ka-hum-kin” (literally, “one mark on the ground”). At Miami a trader keeps his accounts with the Indians in single marks or pencil strokes. For example, an Indian brings to him buck skins, for which the trader allows twelve “chalks.” The Indian, not wishing then to purchase anything, receives a piece of paper marked in this way:

“IIII—IIII—IIII.

J. W. E. owes Little Tiger $3.”

At his next visit the Indian may buy five “marks” worth of goods. The trader then takes the paper and returns it to Little Tiger changed as follows:

“IIII—III.

J. W. E. owes Little Tiger $1.75.”

Thus the account is kept until all the “marks” are crossed off, when the trader takes the paper into his own possession. The value of the purchases made at Miami by the Indians, I was informed, is annually about $2,000. This is, however, an amount larger than would be the average for the rest of the tribe, for the Miami Indians do a considerable business in the barter and sale of ornamental plumage.

What the primitive standard of value among the Seminole was is suggested to me by their word for money, “Tcat-to Ko-na-wa.” “Ko-na-wa” means beads, and “Tcat-to,” while it is the name for iron and metal, is also the name for stone. “Tcat-to” probably originally meant stone. Tcat-to Ko-na-wa (i.e., stone beads) was, then, the primitive money. With “Hat-ki,” or white, added, the word means silver; with “La-ni,” or yellow, added, it means gold. For greenbacks they use the words “Nak-ho-tsi Tcat-to Ko-na-wa,” which is, literally, “paper stone beads.”

Their methods of measuring are now, probably, those of the white man. I questioned my respondent closely, but could gain no light upon the terms he used as equivalents for our measurements.

Table of Contents

I also gained but little knowledge of their divisions of time. They have the year, the name for which is the same as that used for summer, and in their year are twelve months, designated, respectively:

| 1. |

Çla-fŭts-u-tsi, Little Winter. |

| 2. |

Ho-ta-li-ha-si, Wind Moon. |

| 3. |

Ho-ta-li-ha-si-çlak-o, Big Wind Moon. |

| 4. |

Ki-ha-su-tsi, Little Mulberry Moon. |

| 5. |

Ki-ha-si-çlat-o, Big Mulberry Moon. |

| 6. |

Ka-too-ha-si. |

| 7. |

Hai-yu-tsi. |

| 8. |

Hai-yu-tsi-çlak-o. |

| 9. |

O-ta-wŭs-ku-tsi. |

| 10. |

O-ta-wŭs-ka-çlak-o. |

| 11. |

I-ho-li. |

| 12. |

Çla-fo-çlak-o, Big Winter. |

I suppose that the spelling of these words could be improved, but I reproduce them phonetically as nearly as I can, not making what to me would be desirable corrections. The months appear to be divided simply into days, and these are, in part at least, numbered by reference to successive positions of the moon at sunset. When I asked Täl-la-häs-ke how long he would stay at his present camp, he made reply by pointing, to the new moon in the west and sweeping his hand from west to east to where the moon would be when he should go home. He meant to answer, about ten days thence. The day is divided by terms descriptive of the positions of the sun in the sky from dawn to sunset.

Читать дальше