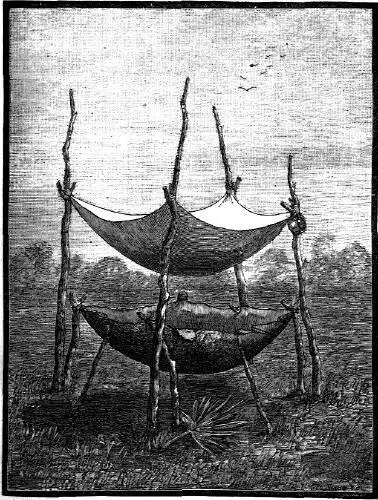

Koonti log.

The Koonti log, so called, was the trunk of a large pine tree, in which a number of holes, about nine inches square at the top, their sides sloping downward to a point, had been cut side by side. Each of these holes was the property of some one of the squaws or of the children of the camp. For each of the holes, which were to serve as mortars, a pestle made of some hard wood had been furnished. ( Fig. 69.)

Fig. 70. Koonti pestles.

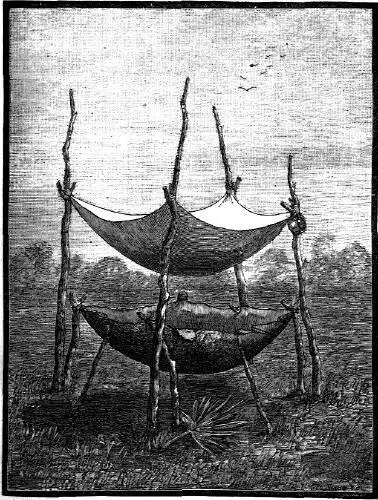

The first step in the process was to reduce the washed Koonti to a kind of pulp. This was done by chopping it into small pieces and filling with it one of the mortars and pounding it with a pestle. The contents of the mortar were then laid upon a small platform. Each worker had a platform. When a sufficient quantity of the root had been pounded the whole mass was taken to the creek near by and thoroughly saturated with water in a vessel made of bark.

Fig. 71. Koonti mash vessel.

The pulp was then washed in a straining cloth, the starch of the Koonti draining into a deer hide suspended below.

Koonti strainer.

When the starch had been thoroughly washed from the mass the latter was thrown away, and the starchy sediment in the water in the deerskin left to ferment. After some days the sediment was taken from the water and spread upon palmetto leaves to dry. When dried, it was a yellowish white flour, ready for use. In the factory at Miami substantially this process is followed, the chief variation from it being that the Koonti is passed through several successive fermentations, thereby making it purer and whiter than the Indian product. Improved appliances for the manufacture are used by the white man.

The Koonti bread, as I saw it among the Indians, was of a bright orange color, and rather insipid, though not unpleasant to the taste. It was saltless. Its yellow color was owing to the fact that the flour had had but one fermentation.

Table of Contents

The following is a summary of the results of the industries now engaged in by the Florida Indians. It shows what is approximately true of these at the present time:

| Acres under cultivation |

|

100 |

| Corn raised |

bushels |

500 |

| Sugarcane |

gallons |

1,500 |

| Cattle |

number owned |

50 |

| Swine |

do. |

1,000 |

| Chickens |

do. |

500 |

| Horses |

do. |

35 |

| Koonti |

bushels |

5,000 |

| Sweet potatoes |

do. |

... |

| Melons |

number |

3,000 |

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

In reference to the way in which, the Seminole Indians have met necessities for invention and have expressed the artistic impulse, I found little to add to what I have already placed on record.

Utensils and implements.—The proximity of this people to the Europeans for the last three centuries, while it has not led them to adopt the white man’s civilization in matters of government, religion, language, manners, and customs, has, nevertheless, induced them to appropriate for their own use some of the utensils, implements, weapons, &c., of the strangers. For example, it was easy for the ancestors of these Indians to see that the iron kettle of the white man was better in every way than their own earthenware pots. Gradually, therefore, the art of making pottery died out among them, and now, as I believe, there is no pottery whatever in use among the Florida Indians. They neither make nor purchase it. They no longer buy even small articles of earthenware, preferring tin instead, Iron implements likewise have supplanted those made of stone. Even their word for stone, “Tcat-to,” has been applied to iron. They purchase hoes, hunting knives, hatchets, axes, and, for special use in their homes, knives nearly two feet in length. With these long knives they dress timber, chop meat, etc.

Weapons.—They continue the use of the bow and arrow, but no longer for the purposes of war, or, by the adults, for the purposes of hunting. The rifle serves them much better. It seems to be customary for every male in the tribe over twelve years of age to provide himself with a rifle. The bow, as now made, is a single piece of mulberry or other elastic wood and is from four to six feet in length; the bowstring is made of twisted deer rawhide; the arrows are of cane and of hard wood and vary in length from two to four feet; they are, as a rule, tipped with a sharp conical roll of sheet iron. The skill of the young men in the use of the bow and arrow is remarkable.

Weaving and basket making.—The Seminole are not now weavers. Their few wants for clothing and bedding are supplied by fabrics manufactured by white men. They are in a small way, however, basket makers. From the swamp cane, and sometimes from the covering of the stalk of the fan palmetto, they manufacture flat baskets and sieves for domestic service.

Uses of the palmetto.—In this connection I call attention to the inestimable value of the palmetto tree to the Florida Indians. From the trunk of the tree the frames and platforms of their houses are made; of its leaves durable water tight roofs are made for the houses; with the leaves their lodges are covered and beds protecting the body from the dampness of the ground are made; the tough fiber which lies between the stems of the leaves and the bark furnishes them with material from which they make twine and rope of great strength and from which they could, were it necessary, weave cloth for clothing; the tender new growth at the top of the tree is a very nutritious and palatable article of food, to be eaten either raw or baked; its taste is somewhat like that of the chestnut; its texture is crisp like that of our celery stalk.

Mortar and pestle.

Mortar and pestle.—The home made mortar and pestle has not yet been supplanted by any utensil furnished by the trader. This is still the best mill they have in which to grind their corn. The mortar is made from a log of live oak (?) wood, ordinarily about two feet in length and from fifteen to twenty inches in diameter. One end of the log is hollowed out to quite a depth, and in this, by the hammering of a pestle made of mastic wood, the corn is reduced to hominy or to the impalpable flour of which I have spoken. ( Fig. 73.)

Canoe making.—Canoe making is still one of their industrial arts, the canoe being their chief means of transportation. The Indian settlements are all so situated that the inhabitants of one can reach those of the others by water. The canoe is what is known as a “dugout,” made from the cypress log.

Читать дальше