Fire making.—The art of fire making by simple friction is now, I believe, neglected among the Seminole, unless at the starting of the sacred fire for the Green Corn Dance. A fire is now kindled either by the common Ma-tci (matches) of the civilized man or by steel and flint, powder and paper. “Tom Tiger” showed me how he builds a fire when away from home. He held, crumpled between the thumb and forefinger of the left hand, a bit of paper. In the folds of the paper he poured from his powder horn a small quantity of gunpowder. Close beside the paper he held also a piece of flint. Striking this flint with a bit of steel and at the same time giving to the left hand a quick upward movement, he ignited the powder and paper. From this he soon made a fire among the pitch pine chippings he had previously prepared.

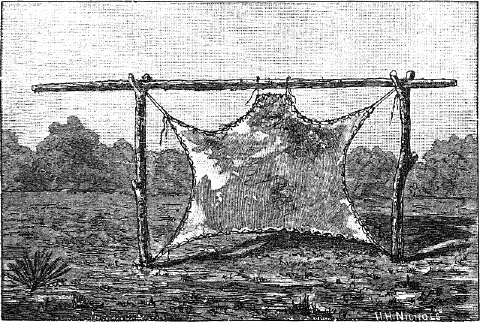

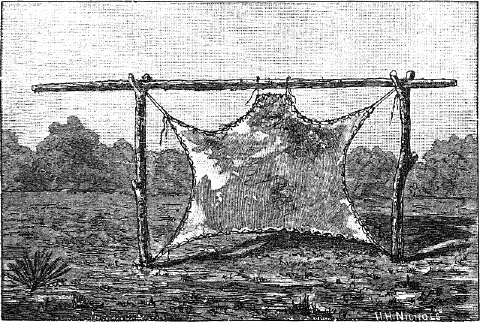

Hide stretcher.

Preparation of skins.—I did not learn just how the Indians dress deer skins, but I observed that they had in use and for sale the dried skin, with the hair of the animal left on it; the bright yellow buckskin, very soft and strong; and also the dark red buckskin, which evidently had passed, in part of its preparation, through smoke. I was told that the brains of the animal serve an important use in the skin dressing process. The accompanying sketch shows a simple frame in use for stretching and drying the skin. ( Fig. 74)

Table of Contents

In my search for evidence of the working of the art instinct proper, i.e., in ornamental or fine art, I found but little to add to what has been already said. I saw but few attempts at ornamentation beyond those made on the person and on clothing. Houses, canoes, utensils, implements, weapons, were almost all without carving or painting. In fact, the only carving I noticed in the Indian country was on a pine tree near Myers. It was a rude outline of the head of a bull. The local report is that when the white men began to send their cattle south of the Caloosahatchie River the Indians marked this tree with this sign. The only painting I saw was the rude representation of a man, upon the shaft of one of the pestles used at the Koonti log at Horse Creek. It was made by one of the girls for her own amusement.

I have already spoken of the art of making silver ornaments.

Music.—Music, as far as I could discover, is but little in use among the Seminole. Their festivals are few; so few that the songs of the fathers have mostly been forgotten. They have songs for the Green Corn Dance; they have lullabys; and there is a doleful song they sing in praise of drink, which is occasionally heard when the white man has sold Indians whisky on coming to town. Knowing the motive of the song, I thought the tune stupid and maudlin. Without pretending to reproduce it exactly, I remember it as something like this:

I give a free translation of the Indian words and an approximation to the tune. The last note in this, as in the lullaby I noted above, is unmusical and staccato.

Table of Contents

I could learn but little of the religious faiths and practices existing among the Florida Indians. I was struck, however, in making my investigations, by the evident influence Christian teaching has had upon the native faith. How far it has penetrated the inherited thought of the Indian I do not know. But, in talking with Ko-nip-ha-tco, he told me that his people believe that the Koonti root was a gift from God; that long ago the “Great Spirit” sent Jesus Christ to the earth with the precious plant, and that Jesus had descended upon the world at Cape Florida and there given the Koonti to “the red men.” In reference to this tradition, it is to be remembered that during the seventeenth century the Spaniards had vigorous missions among the Florida Indians. Doubtless it was from these that certain Christian names and beliefs now traceable among the Seminole found way into the savage creed and ritual.

I attempted several times to obtain from my interpreter a statement of the religious beliefs he had received from his people. I cannot affirm with confidence that success followed my efforts.

He told me that his people believe in a “Great Spirit,” whose name is His-a-kit-a-mis-i. This word, I have good reason to believe, means “the master of breath.” The Seminole for breath is His-a-kit-a.

I cannot be sure that Ko-nip-ha-tco knew anything of what I meant by the word “spirit.” I tried to convey my meaning to him, but I think I failed. He told me that the place to which Indians go after death is called “Po-ya-fi-tsa” and that the Indians who have died are the Pi-ya-fits-ul-ki, or “the people of Po-ya-fi-tsa.” That was our nearest understanding of the word “spirit” or “soul.”

Table of Contents

As the Seminole mortuary customs are closely connected with their religious beliefs, it will be in place to record here what I learned of them. The description refers particularly to the death and burial of a child.

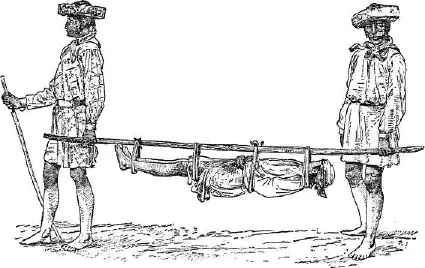

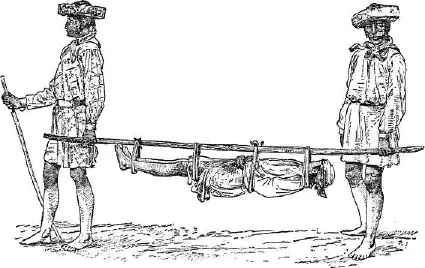

Seminole bier.

The preparation for burial began as soon as death had taken place. The body was clad in a new shirt, a new handkerchief being tied about the neck and another around the head. A spot of red paint was placed on the right cheek and one of black upon the left. The body was laid face upwards. In the left hand, together with a bit of burnt wood, a small bow about twelve inches in length was placed, the hand lying naturally over the middle of the body. Across the bow, held by the right hand, was laid an arrow, slightly drawn. During these preparations, the women loudly lamented, with hair disheveled. At the same time some men had selected a place for the burial and made the grave in this manner: Two palmetto logs of proper size were split. The four pieces were then firmly placed on edge, in the shape of an oblong box, lengthwise east and west. In this box a floor was laid, and over this a blanket was spread. Two men, at next sunrise, carried the body from the camp to the place of burial, the body being suspended at feet thighs, back, and neck from a long pole ( Fig. 75). The relatives followed. In the grave, which is called “To-hŏp-ki”—a word used by the Seminole for “stockade,” or “fort,” also, the body was then laid the feet to the east. A blanket was then carefully wrapped around the body. Over this palmetto leaves were placed and the grave was tightly closed by a covering of logs. Above the box a roof was then built. Sticks, in the form of an X, were driven into the earth across the overlying logs; these were connected by a pole, and this structure was covered thickly with palmetto leaves. ( Fig. 76.)

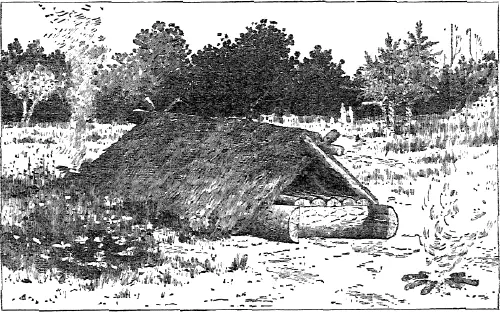

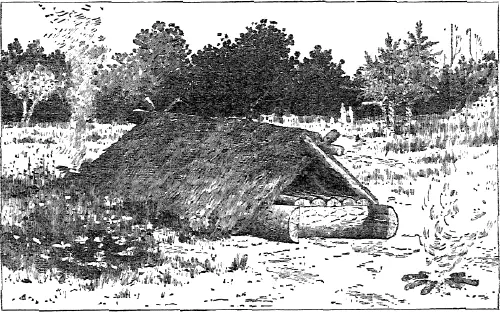

Fig. 76. Seminole grave.

The bearers of the body then made a large fire at each end of the “To-hŏp-ki.” With this the ceremony at the grave ended and all returned to the camp. During that day and for three days thereafter the relatives remained at home and refrained from work. The fires at the grave were renewed at sunset by those who had made them, and after nightfall torches were there waved in the air, that “the bad birds of the night” might not get at the Indian lying in his grave. The renewal of the fires and waving of the torches were repeated three days. The fourth day the fires were allowed to die out. Throughout the camp “medicine” had been sprinkled at sunset for three days. On the fourth day it was said that the Indian “had gone.” From that time the mourning ceased and the members of the family returned to their usual occupations.

Читать дальше