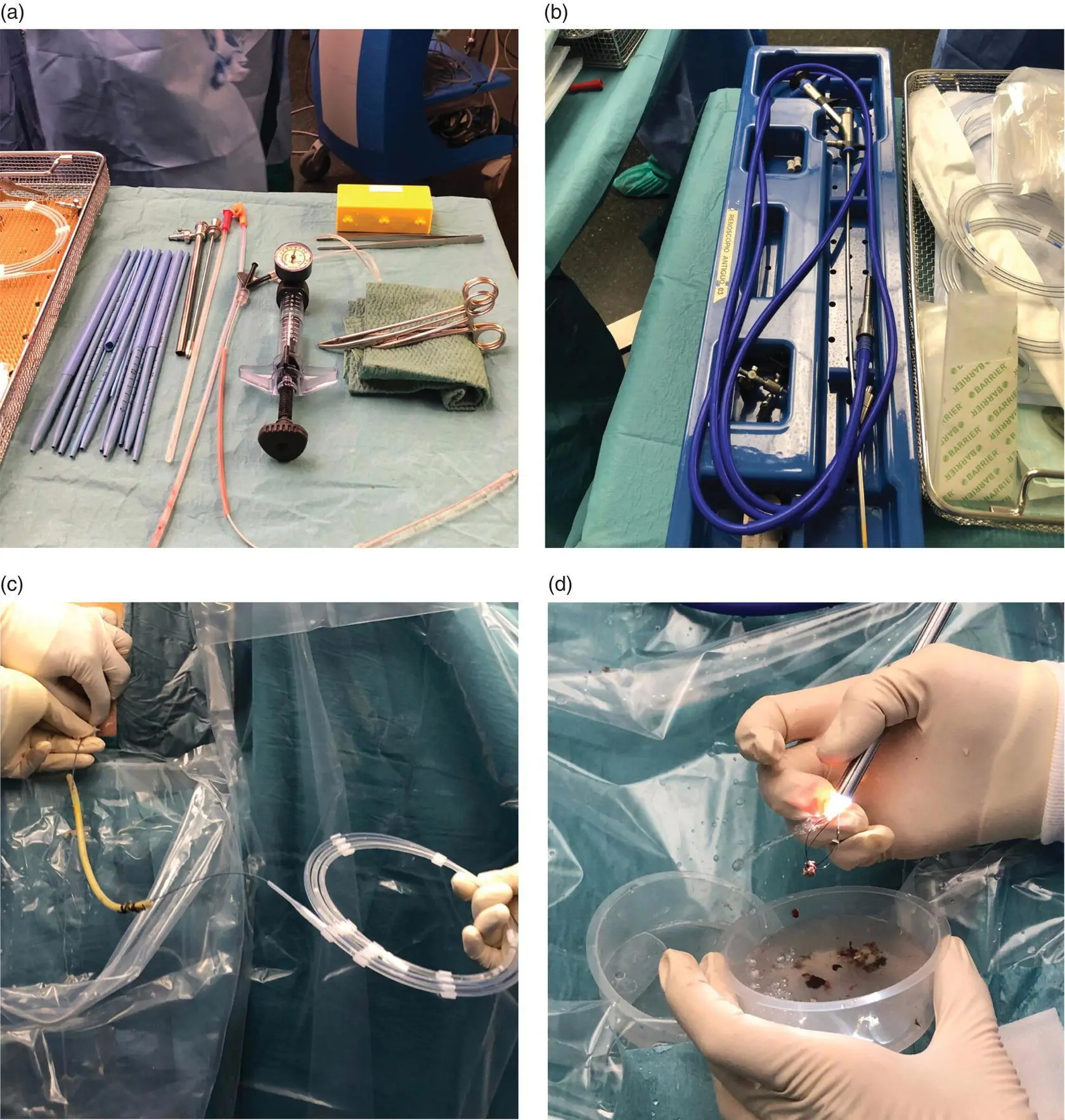

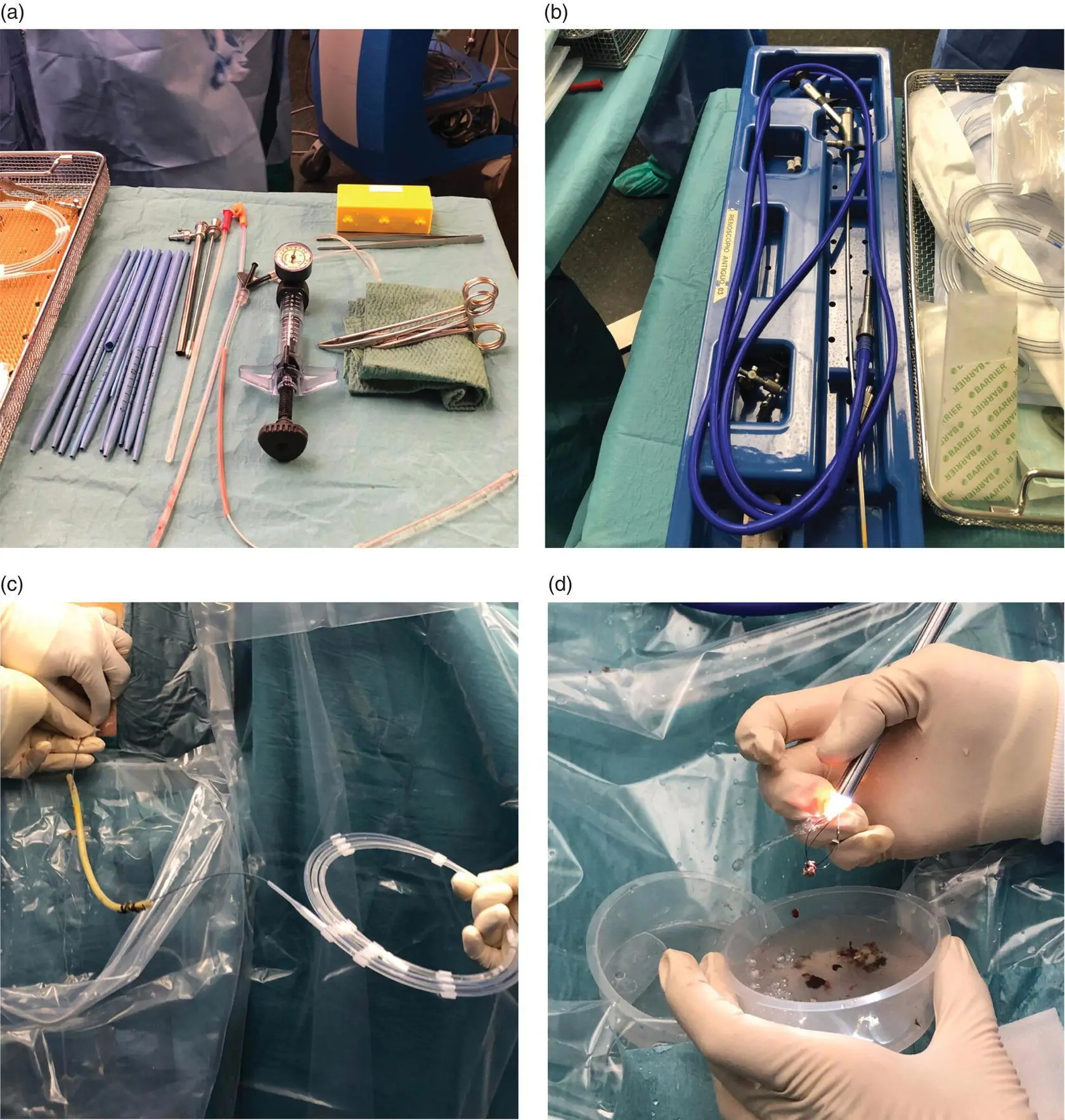

A 5‐mm working channel nephroscope ( Figure 15.1b) is normally employed to clean the residual cavity [24]. Abundant normal saline serum together with a grasper and a Dormia basket can be used to evacuate the abundant, fluffy, cloud‐like pus and loose necrotic material. A 32‐Fr Nelaton drain is reintroduced along the sinus track to permit subsequent postoperative cleaning. The drainage tube is kept in place until the output is less than 10 ml/day and is then withdrawn, the main advantage being that necrotic tissue can be removed as many times as necessary without the need for formal reoperation. Antibiotics are usually administered while the drain is in place.

Endoscopic (Endoluminal) Approach

The endoscopic approach is a less invasive approach consisting of extracting the necrosis by natural orifices and has now become a promising option for the management of IPN patients. The technique was initially defined in 1996 by Baron et al. [25] and since then the results reported on different series in the literature show that mortality has been reduced to 5.6% with an overall complication rate of 28%. More recently, a randomized controlled trial comparing the endoscopic and surgical approaches revealed significantly fewer complications and rate of pancreatic fistula in the endoscopic arm [24]. As with all other techniques, serious specific complications have been reported, such as bleeding, perforation of the abdominal cavity, and peritonitis [18]. Although the endoscopic approach via the duodenum has been described, in practice the transgastric route is usually preferred as it can also be used to assess the integrity of the duct and has the further advantage of providing a diagnostic and therapeutic option for associated pancreatic and biliary pathologies.

The endoscopic approach is normally performed under general anesthesia but can also be carried out under sedation with midazolam and fentanyl. The post‐inflammatory pancreatic necrosis behind the posterior stomach wall is located and punctured. With successive balloon dilatations, a window of up to 2 cm in length is obtained for direct lavage, through which a gastroscope is passed to enable manipulation of the necrosis with forceps. Optionally, additional transgastric pigtails may also be inserted to facilitate drainage and ensure the reproducibility of the procedure [26].

Figure 15.1 (a, b) Amplatz and dilatators used to dilate the drainage tract and facilitate nephroscope insertion. (c) The previous drain is used as a guide to introduce the wire under fluoroscopic guidance. (d) Necrotic tissue and debris are extracted with the Dormia basket under direct visualization.

Source: courtesy of Patricia Sánchez‐Velázquez.

One of the technique’s drawbacks is that at least three procedures are usually required due to the small size of the window in the gastric wall and the poor capacity of the devices used to grasp the necrosis. Also, since it is quite a complex operation, it is performed at only a few centers, including tertiary referral centers, and is heavily reliant on the endoscopist’s experience. Although the published results seem to be satisfactory and mortality is very low, up to 40% of patients require additional placement of percutaneous drains to eliminate new areas of necrosis or collections, and between 20 and 28% require further surgical treatment. However, it has the great advantage of being less invasive and of providing further endoscopic therapy options. Moreover, the pancreatic juice drains directly into the gastric/duodenal lumen, so the rate of pancreatic fistula is reduced to less than 10%, as has been shown by the only randomized controlled trial published on this topic [27].

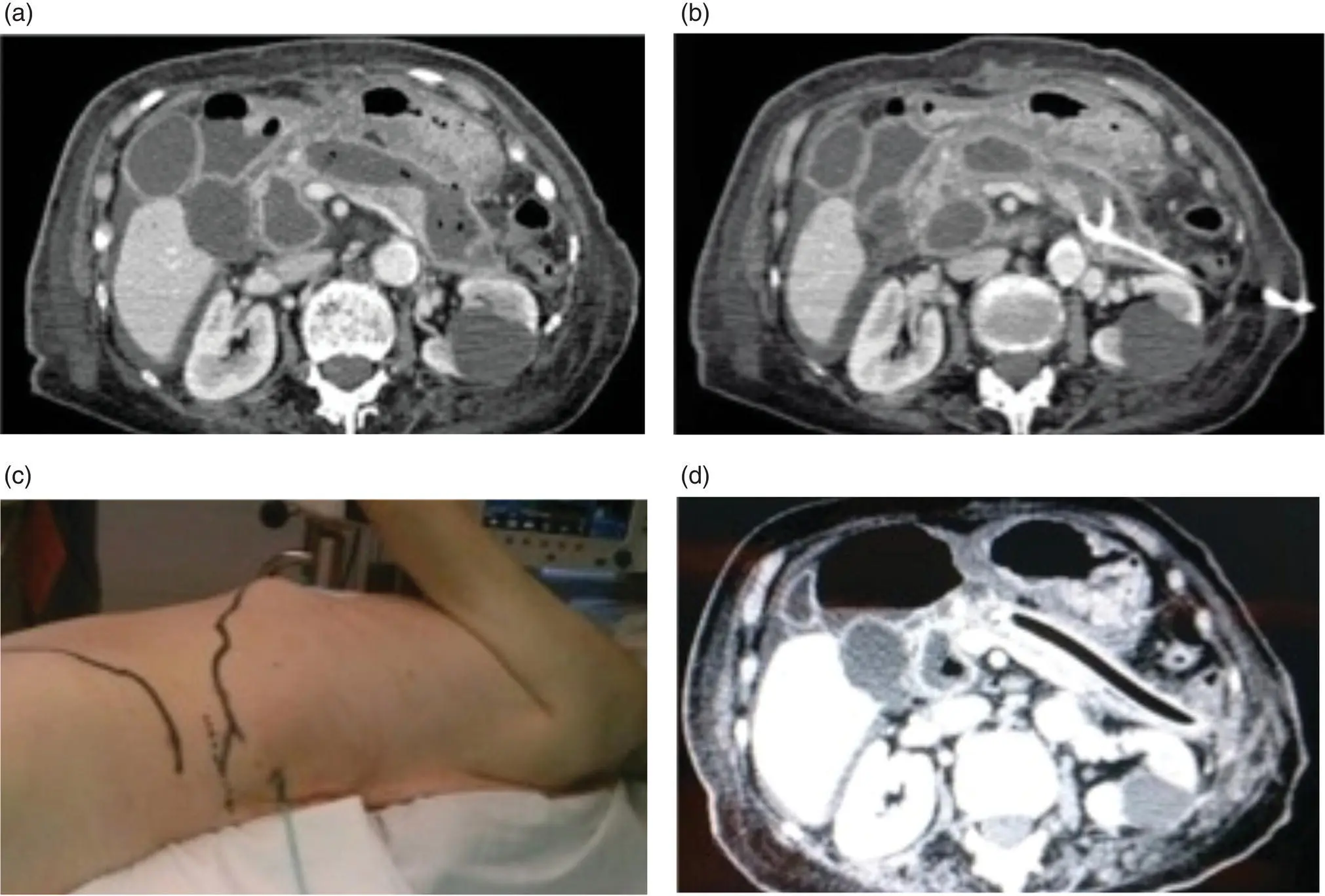

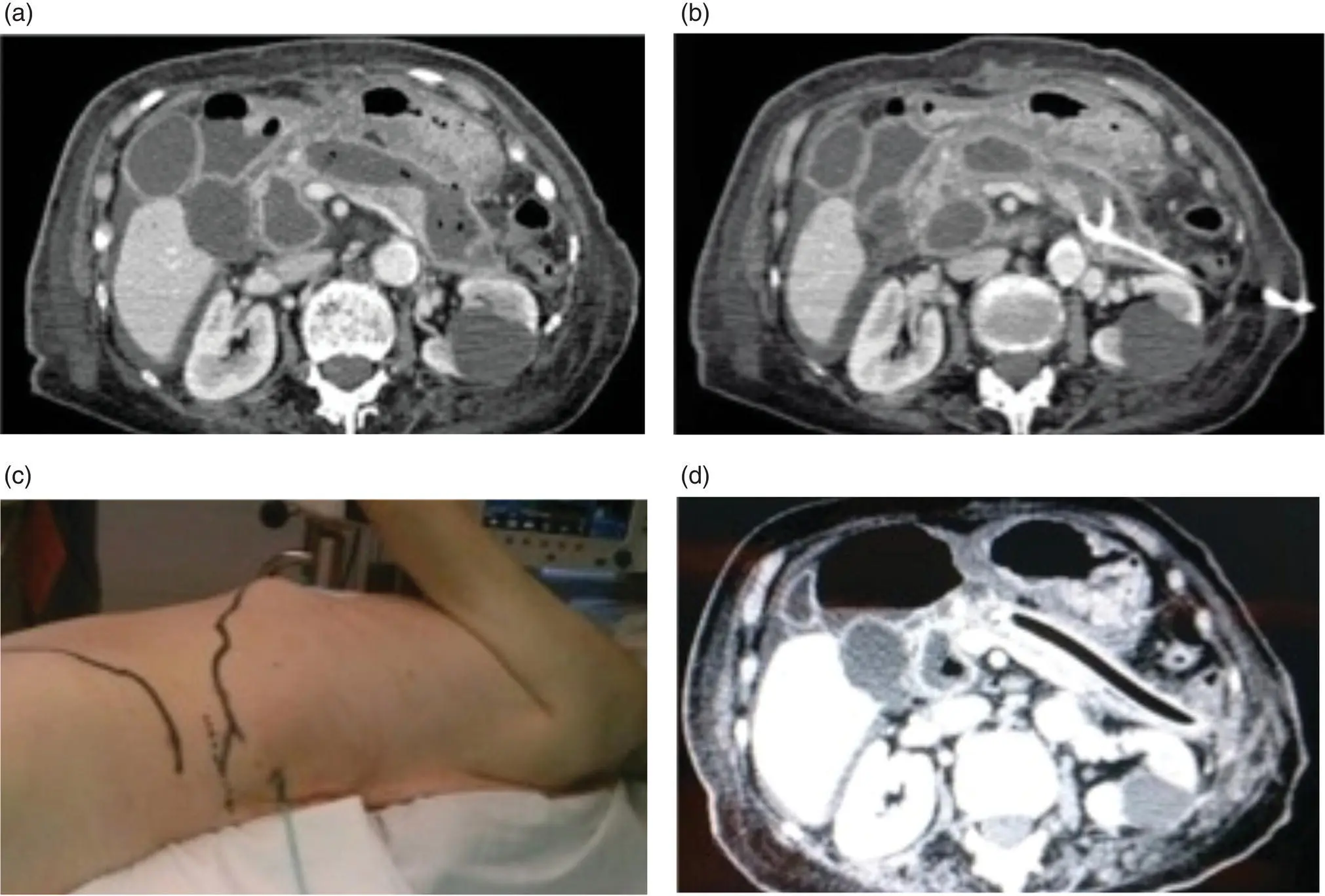

With the rise of minimally invasive techniques, retroperitoneal pancreatic necrosectomy has become more widespread than open necrosectomy and the transperitoneal laparoscopic approach. Ideally, it should be applied to pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis in the left pancreas, lesser sac, and left paracolic gutter ( Figure 15.2a,b).

The technique was initially described in 1998 by Gambiez et al. [28], was later defined by Horvath et al. [29] as video‐assisted retroperitoneal debridement (VARD), and then popularized by van Santvoort et al. [14]. This approach is accepted as a secondary therapeutic procedure after failure of percutaneous drainage, which indeed is crucial for reaching the pancreatic lodge. It should be noted that the purpose of this procedure is to facilitate percutaneous drainage rather than to completely evacuate necrotic fluid from the cavity. The surgeon will find it easier to locate the necrosis within the cavity if a second anterior or caudal drain has been placed, although this is not essential.

The patient is placed in a modified lateral decubitus position ( Figure 15.2c). The entire abdomen and flank are prepared and draped within the sterile field to allow adequate access to the retroperitoneum. A small incision is performed below the 12th rib following the previously inserted drainage. The pancreatic cell is reached via the left retroperitoneal access without opening the peritoneum, passing behind the splenic flexure of the colon and spleen. This dissection is performed bluntly under digital control. Once lodged in the pancreatic area, a laparoscopic camera is inserted through the small incision to view the area. Care must be taken to avoid injuring the blood vessels, so that adherent or necrotic tissue that cannot be freed easily should be left in place. The necrotic tissue is grasped and removed by suction and forceps. At the end of the procedure a large drain should be inserted to allow postoperative washes ( Figure 15.2d).

Although this approach has been claimed to be the standard for WON in the left pancreas, real data on patient outcomes is scarce and limited to case series [14,30,31], which still report a mortality of up to 40%. The technique is also not exempt from complications, such as colonic fistula, gastric and duodenal perforation, enteric fistula, pancreatic fistula, and retroperitoneal hemorrhage, and therefore should be confined to centers with an appropriately experienced multidisciplinary team.

Figure 15.2 (a) Infected pancreatic necrosis by abdominal tomography. (b) Placement of a retroperitoneal percutaneous catheter in pancreatic lodge. (c) Position of the patient for video‐assisted retroperitoneal debridement (VARD). (d) After VARD, a 32‐Fr drain is placed in the pancreatic lodge to enable continuous flushes.

Source: courtesy of Patricia Sánchez‐Velázquez.

Laparoscopic Transperitoneal Approach

This procedure is the least used minimally invasive approach. Its main drawback is that the patient must be in a stable clinical condition to allow adequate tolerance of pneumoperitoneum. Furthermore, the large inflammatory component of omental and mesenteric fat may hinder access to the lesser sac and retroperitoneum and preclude correct drainage of the pancreatic lodge.

The laparoscopic transperitoneal approach achieves a lower overall complication rate than conventional open necrosectomy (particularly with regard to pancreatic fistula), fewer wound infections, and a shorter postoperative stay. Based on the data reported in the literature, 80% of these cases will not require additional surgical procedures. Open conversion is below 20% [32] while the reported mortality rate is close to 10%. However, most published studies include retrospective series of less than 10 selected patients and as many do not include relevant data their results should be assessed with caution [33,34].

Читать дальше