33 33 Jain S, Padhan R, Bopanna S, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic step‐up therapy is an effective minimally invasive approach for infected necrotizing pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci 2020; 65(2):615–622.

34 34 Al‐Sarireh B, Mowbray NG, Al‐Sarira A, et al. Can infected pancreatic necrosis really be managed conservatively? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 30(11):1327–1331.

35 35 Mohan BP, Jayaraj M, Asokkumar R, et al. Lumen apposing metal stents in drainage of pancreatic walled‐off necrosis, are they any better than plastic stents? A systematic review and meta‐analysis of studies published since the revised Atlanta classification of pancreatic fluid collections. Endosc Ultrasound 2019; 8(2):82–90.

36 36 Baron TH, DiMaio CJ, Wang AY, Morgan KA. American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update: management of pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterology 2020; 158(1):67–75.e1.

37 37 DeSimone ML, Asombang AW, Berzin TM. Lumen apposing metal stents for pancreatic fluid collections: recognition and management of complications. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(9):456–463.

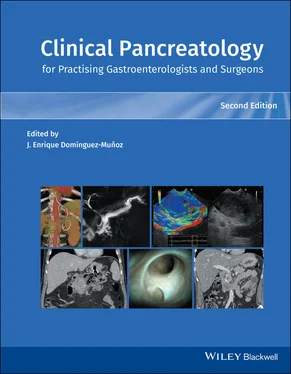

15 Minimally Invasive Surgical Necrosectomy in Clinical Practice : Indications, Technical Issues, and Optimal Timing

Patricia Sánchez‐Velázquez, Fernando Burdío, and Ignasi Poves †

Department of Surgery, Hospital del Mar and Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Acute necrotizing pancreatitis (ANP) is still a life‐threatening disease associated with high morbidity and up to 60% mortality [1]. It was classically accepted that infected pancreatic necrosis (IPN), confirmed by a positive culture of the necrosis after fine‐needle aspiration (FNA) [2], was an absolute indication for emergent surgical debridement [3], especially in the presence of multiorgan failure [4]. However, it seems that the diagnosis of IPN alone is no longer an absolute indication for direct surgical intervention, or at least that it is extremely challenging to determine the best timing for intervention, or even to decide whether surgery is the best option. In this regard, in a few years we have moved from highly proactive management [5] to a conservative approach. The first randomized controlled trial on this topic in the late 1990s showed that postponing surgery by at least 12 days from onset of symptoms significantly reduced complications [6]. Indeed, it seems that delaying the intervention to the third or fourth week of symptoms tends to reduce mortality compared with the first 14 days after onset of symptoms [7]. The rationale for this delay is based on the fact that a new “hit” in these already critical patients would have a negative impact on outcomes. The international guidelines now advise this cutoff and do not recommend operations on ANP in the first two weeks from onset, as long as the patient responds favorably to medical management [8,9].

The surgical treatment of IPN has evolved rapidly in recent years. When open necrosectomy and debridement were traditionally considered the gold standard [10,11], most patients were subjected to surgical explorations, removal of necrotic debris through the gastrocolic route, and multiple drain placements. This hazardous approach was classically associated with a high rate of postoperative complications, reoperations and mortality, as well as being frequently associated with postoperative diabetes and exocrine pancreas insufficiency [1,12]. However, the new alternative minimally invasive techniques have been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality [13]. In a landmark study published in 2010, van Santvoort et al. [14] established the so‐called “step‐up” approach as the new ANP gold‐standard surgical procedure. This consists of a stepwise rise in the use of invasive techniques, since the success of surgery in this setting depends on controlling the source of infection rather than completely removing the infected necrosis [15]. In fact, severe pancreatitis is more likely to be related to extrapancreatic organ failure than to local complications [16].

The goal of this chapter is thus to describe the different minimally invasive approaches, which can be classified into four broad groups: percutaneous, retroperitoneal, laparoscopic (transperitoneal), and endoscopic (endoluminal).

The aim of the percutaneous approach is to improve the patient’s condition and to delay surgery until IPN is well defined (walled‐off necrosis, or WON). Necrosis demarcation facilitates necrosectomy and reduces complications related to drainage and debridement. Although there is some evidence of the safety of drainage placement in the absence of WON, instauration of the necrosis is normally preferred before performing any interventionism, so that it has become the standard practice for some years.

In 1998, Freeny et al. [17] first reported positive results using percutaneous drains inserted under radiological control for initial IPN management. They found that subsequent surgery was avoided in 47% of the cases and sepsis controlled in 74%. Successive studies describe a similar technique, namely inserting computed tomography (CT)‐ or ultrasound‐guided percutaneous drains of 8–28 Fr to evacuate infected peripancreatic collections, combined with antibiotics. Neither the size nor the number of drains seems to affect patient outcomes [18]. Multiple drains may be needed to replace previous ones in order to increase the inserted catheter diameters and saline flushes are often applied at 8‐hour intervals. A recent systematic review of 286 patients found that percutaneous drainage was successful in 44% of the patients without requiring necrosectomy [18], while only 35% of the patients in the PANTER trial had no need for further interventions after this procedure [14]. The clinical response should be assessed 72 hours after placement of the first drain to assess whether a second is required [14]. Similarly, there is no clear consensus on the timing of drainage placement, but most studies recommend the second and third weeks from onset of symptoms, before WON [19]. Questions have been raised about the usefulness of the drain in the early stages of the disease and whether it can prevent later complications such as pancreas fistula or bleeding. In this regard, an ongoing randomized clinical trial (POINTER) is being carried out to determine whether immediate drainage is more effective than postponing intervention [20].

The secondary goal of this strategy is to chart a path for use as a guide when locating the anatomical space to be drained, which is the preliminary step for further procedures, should the conservative treatment fail (see following chapters) [21].

Sinus tract endoscopy is a special variant of percutaneous treatment and forms part of the “step‐up” approach. This technique was first described by Carter et al. [22], who hypothesized that complications and multiorgan failure could be reduced by minimizing the massive inflammatory “hit” of open pancreatic necrosectomy. In fact, sinus tract endoscopy was described as a procedure that followed open necrosectomy in order to preclude further reoperations, although the initial indication was extended to the primary management of retroperitoneal peripancreatic sepsis, as patients developed fewer organ dysfunctions and postsurgical recovery was faster.

This approach would be ideal for treating laterally placed WON (i.e. at more than 1–2 cm from the stomach and duodenal wall [23]), whereas it is not appropriate for necrotic collections in and around the pancreatic head, which are more suitable for transmural drainage (see next section).

The procedure takes place under general anesthesia and fluoroscopic guidance with the patient in the right lateral decubitus position, using the previous drain as the point of entry. The drain tract is dilated by a 30‐Fr balloon to allow the insertion of Amplatz dilators and sheaths ( Figure 15.1a).

Читать дальше