See chapter 20, ‘Politics, Government and Social Movements’, for more on anti-globalization and anti-capitalist movements.

With its origins in the work of Marx and Marxism, world-systems theory has faced some similar criticisms. First, the theory tends to emphasize the economic dimension of social life and underplays the role of culture in explanations of social change (Barfield 2000). It may be argued, for example, that one reason why Australia and New Zealand were able to move out of the periphery more easily than others was because of their close cultural ties to British industrialization, which allowed an industrial culture to take root more quickly.

Second, the theory underplays the role of ethnicity, which is seen merely as a defensive reaction against the globalizing forces of the world-system. Therefore, major differences of religion and language are not considered to be particularly significant. Finally, Wallerstein’s thesis is seen as overly state-centred, concentrating on the nation-state as a central unit of analysis. But this makes it more difficult to theorize the process of globalization, which involves transnational corporations and interests that operate across nation-state boundaries (Robinson 2011). Of course, Wallerstein and his supporters have sought to counter these arguments over recent years.

Contemporary significance

Wallerstein’s work has been important in alerting sociologists to the interconnected character of the capitalist world economy and its globalizing effects. He therefore has to be given credit for early recognition of the significance of globalization processes, even though his emphasis on economic activity is widely seen as limiting. Wallerstein’s approach has attracted many scholars, and, with an institutional base in the Fernand Braudel Center and an academic journal devoted to its extension – the Journal of World-Systems Research (since 1995) – world-systems analysis is now an established research tradition.

Are there historical examples of countries within the ‘core’ slipping into the semi-periphery or even the periphery? Why do you think the 2008 financial crash did not lead to a raft of countries being forced out of the world-system core?

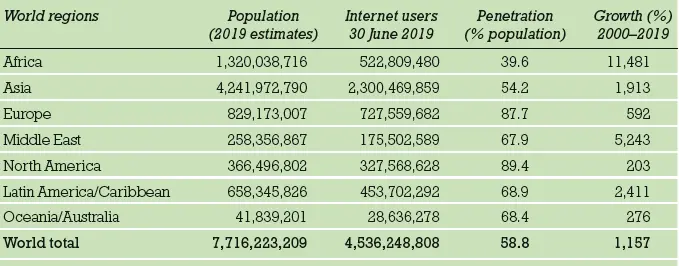

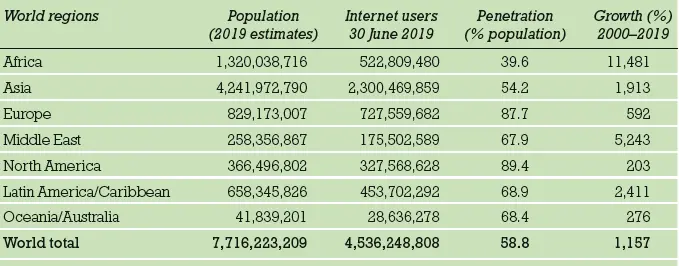

In countries with highly developed telecommunications infrastructures, homes and offices have multiple links to the outside world, including landline and mobile phones, digital, satellite and cable television, electronic mail and the internet. The internet has emerged as the fastest-growing communications tool ever developed. In mid-1998, around 140 million people worldwide were using it. By the end of 2000 this had risen to over 360 million, and, by mid-2019, over 4.5 billion people across the world were internet users, almost 60 per cent of the global human population (table 4.3).

Most superfast broadband is delivered not by satellite but via the much older method of transoceanic cables, laid on or under the seabed. The 6,600 kilometre Marea cable, laid between Spain and Virginia in the US, was a joint venture by Facebook and Microsoft and the first linking the US and southern Europe.

Table 4.3 The global spread of internet usage, 2019: mid-year estimates

Source : Adapted from www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm.

These technologies facilitate what Harvey (1989) calls time–space compression. For instance, two individuals located on opposite sides of the planet – say, Tokyo and London – can not only hold a conversation in real time but also send documents, audio, images, video, and much more. Hence, the relative distance between places is dramatically reduced and the world as experienced is effectively shrinking, allowing people to become conscious of a single global human society.

Widespread use of the internet and smartphones is deepening and accelerating processes of globalization as more people are interconnected, including those in places that were previously isolated or poorly served by traditional communications. Rapid telecommunications infrastructure is not evenly distributed, but a growing number of countries can access global communication networks, and, as table 4.3 shows, the fastest growth in internet access over the twenty-first century is in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, Latin America and the Caribbean, as these regions begin to catch up.

The spread of information technology has both expanded the possibilities for cultural contact between people around the globe and facilitated the flow of information about people and events. Every day, news and information are brought into people’s homes, linking them directly and continuously to the outside world. Some of the most gripping (and disturbing) events of recent times – the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, pro-democracy protests and the crackdown in China’s Tiananmen Square (also in 1989), terrorist attacks on America in 2001 and the occupation of Egypt’s Tahrir Square in 2011 as the ‘Arab Spring’ developed – have unfolded before a truly global audience. The interactive character of digital technologies has led to ‘citizen journalists’ helping to produce the news by reporting ‘direct from the scene’ of world events over the internet.

The shift to a global outlook has two significant dimensions. First, people increasingly perceive that their responsibility does not stop at national borders. Disasters and injustices facing people around the world are no longer misfortunes that cannot be tackled but legitimate grounds for action and intervention. A growing assumption has arisen that ‘the international community’ has an obligation to act in crisis situations to protect the human rights of individuals. In the case of natural disasters, interventions take the form of humanitarian relief and technical assistance. There have also been stronger calls in recent years for intervention and peacekeeping forces in civil wars and ethnic conflicts, though such mobilizations are politically problematic compared to those for natural disasters.

Second, a global outlook seems to be threatening or undermining many people’s sense of national (or nation-state) identity. Local cultural identities are experiencing powerful revivals at a time when the traditional hold of the nation-state is undergoing profound transformation. In Europe, people in Scotland and the Catalonia region of Spain may be more likely to identify as Scottish or Catalan – or simply as Europeans – rather than as British or Spanish. A referendum on Scottish independence from the UK in September 2014 was lost, but 45 per cent of the population voted ‘Yes’. An unofficial vote in Catalonia in October 2017 saw 92 per cent voting for independence from Spain. In some regions, nation-state identification may be waning as globalization loosens people’s orientation to the states in which they live.

The interweaving of cultures and economies

For some socialist and Marxist sociologists, although culture and politics play a part in globalizing trends, these are underpinned by capitalist economic globalization and the continuing pursuit of profits. Martell (2017: 4), for example, argues that ‘it is difficult to see many areas of globalization where lying behind them are not also underlying economic structures that affect the equality or power relations with which globalization is produced or received, or economic incentives to do with making money.’ This viewpoint accepts the multidimensional character of globalization but rejects the notion that cultural, political and economic factors should be given equal weight. Analysing ‘material interests’ and the way these are pursued remains the key to understanding globalization in this neo-Marxist perspective.

Читать дальше