The legacy of colonialism and the postcolonialist critique of sociology are discussed in chapter 3, ‘Theories and Perspectives’.

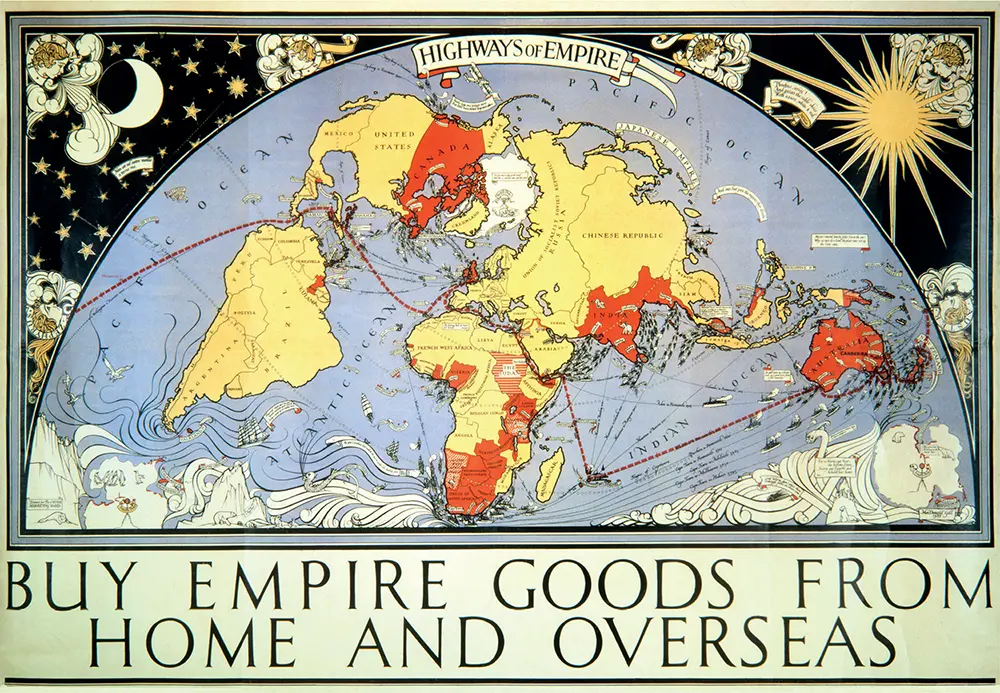

Seen globally, the majority world of developing countries lies in the southern hemisphere, and you may see them collectively described as the Global South, contrasted with the minority world of developed countries in the Global North. Geographically, this is a rough and ready generalization because, for example, Australia, New Zealand and Chile are in the Global ‘South’ but are high or middle-high income, developed countries that are typical of the Global ‘North’ (World Bank 2020a). Also, as countries in the Global South continue to develop economically, this simple geographic division of the world becomes less accurate.

Yet the shift in terminology used here was never intended to be purely a descriptive alternative. Rather, it marks a political intervention in debates on global interdependence, particularly the notion that intensifying the connections between countries through globalization will benefit them all. Dados and Connell (2012: 13) argue that the term ‘Global South’ ‘references an entire history of colonialism, neo-imperialism, and differential economic and social change through which large inequalities in living standards, life expectancy, and access to resources are maintained.’ Indeed, Mahler (2018: 32) argues that some regions within the Global North are also disadvantaged and exploited, while wealth and power continue to flow to a minority. Simply put, ‘there are Souths in the geographic North and Norths in the geographic South.’

Framing global relations in this way looks to build solidarity among all of those that are negatively impacted by global capitalism, regardless of geographical location, and it is clear that this is not an attempt to produce a ‘neutral’ classification. The model is based not on classifying the world’s countries but on relations of inequality, power and domination, both between and within national societies. In this sense, it is a very different way of looking at and thinking about global issues that is not directly comparable to the other classification schemes discussed above.

It is clear that all classification schemes have pros and cons, so how do we choose? One way of moving forward that may become more common in the future is to avoid committing to any of these broad, generalizing schemes that slice up, arrange and rearrange the diverse type of societies in the world. Instead, we might just try to be clearer about what we mean in the context of what we are discussing at the time. Toshkov (2018) forcibly makes this case, arguing that, ‘If you mean the 20 poorest countries in the world, say the 20 poorest countries in the world, not countries of the Global South. If you mean technologically underdeveloped countries, say that and not countries of the Third World. If you mean rich, former colonial powers from Western Europe, say that and not the Global North. It takes a few more words, but it is more accurate and less misleading.’

Sociology is a discipline that tries to draw the broadest, legitimate, general conclusions that are consistent with the available evidence, and this generalizing approach is important and necessary. Yet Toshkov’s argument is persuasive and may be more widely adopted in the future. We will go some way in this direction in the rest of the chapter (and elsewhere), though, in practice, we will often use developed/developing countries where our source material adopts this framing. Where they are appropriate, we will also use majority/minority worlds, high-/medium-/low-income countries, colonialism and postcolonialism, and a geographical version of the rough Global South/Global North distinction.

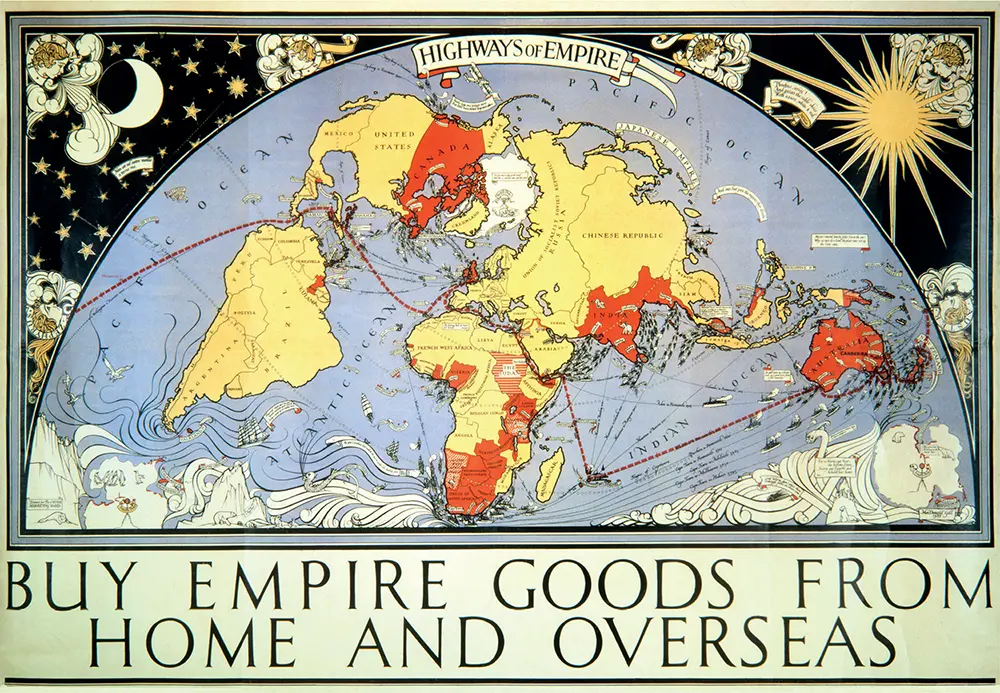

By the early twentieth century, Britain’s colonial expansion had created ‘an empire on which the sun never sets’ covering over one-fifth of the global population. This advertisement presents the empire, coloured red, along with trading routes.

List the main aspects of each classification scheme and look for elements of difference and similarity. Are all of these varied schemes really just different ways of talking about the same thing, or are they actually focusing on very different issues and problems?

There is also a discussion of classification schemes relating to inequalities in chapter 6, ‘Global Inequality’.

Sociology’s founders all saw the modern world as, in crucial ways, a radically different place than it had been in the recent past. Yet social change is difficult to define because, in a sense, society is changing or ‘in process’ all of the time. Sociologists try to decide when there has been fundamental social change leading to a new form or structure of society and then look for explanations of what brought such change about. Identifying major shifts means showing that there has been an alteration in the underlying structure of an institution or society over a specified period of time. All accounts of social change must also show what remains stable, as a baseline against which to measure change. Auguste Comte described this kind of analysis as the study of social dynamics (processes of change) and social statics (stable institutional patterns).

In the rapidly moving world of today there are still continuities with the distant past. For example, major religions such as Christianity and Islam retain their ties with ideas and practices initiated in ancient times. Yet most institutions in modern societies change more rapidly than those of earlier civilizations, and we can identify the main elements that consistently influence patterns of social change as economic development, socio-cultural change and political organization. These can be analysed separately, though in many cases a change in one element brings about change in the others.

Many human societies and groups thrive and generate wealth even in the most inhospitable regions of the world. On the other hand, some survive quite well without exploiting the natural resources at their disposal. For example, Alaskans have been able to develop oil and mineral resources to produce economic development, while hunting and gathering cultures have frequently lived in fertile regions without ever becoming pastoralists or farmers.

Physical environments may enable or constrain the kind of economic development that is possible. The indigenous people of Australia have never stopped being hunters and gatherers, since the continent contained hardly any indigenous plants suitable for regular cultivation or animals that could be domesticated for pastoral production. Similarly, the world’s early civilizations originated in areas with rich agricultural land such as river deltas. The ease of communication across land and the availability of sea routes are also important: societies cut offfrom others by mountain ranges, impassable jungles or deserts often remain relatively unchanged over long periods of time.

However, the physical environment is not just a constraint but also forms the basis for economic activity and development, as raw materials are turned into useful or saleable things. The primary economic influence during the period of modernity has been the emergence of capitalist economic relations. Capitalism differs in a fundamental way from previous production systems, because it involves the constant expansion of production and the accumulation of wealth without limits. In traditional systems, levels of production were fairly stable, as they were geared to habitual, customary needs. But capitalism promotes the constant revision of production technology, a process into which science is increasingly drawn. The rate of technological innovation in modern industry is vastly greater than in any previous type of economy, and raw materials have been used in production processes in quantities undreamed of in earlier times.

Читать дальше