For many sociologists, globalization refers to a set of largely unplanned processes, involving multidirectional flows of things, people and information across the planet (Ritzer 2009). However, although this definition highlights the increasing fluidity or liquidity of the contemporary world, many scholars also see globalization as the simple fact that individuals, companies, groups and nations are becoming ever more interdependent as part of a single global community. As we saw in the introduction to this chapter, the process of growing global interdependence has been occurring over a very long period of human history and is certainly not restricted to recent decades (Nederveen Pieterse 2004; Hopper 2007). Therborn (2011: 2) makes this point well:

Segments of humanity have been in global, or at least transcontinental, transoceanic, contact for a long time. There were trading links between ancient Rome and India about 2,000 years ago, and between India and China. The foray of Alexander of Macedonia into Central Asia 2,300 years ago is evident from the Greeklooking Buddha statues in the British Museum. What is new is the mass of contact, and the contact of masses, mass travel and mass selfcommunication.

As Therborn suggests, contemporary sociological debates are focused much more on the sheer pace and intensity of contemporary globalization. It is this central idea of an intensification of the process that marks this period out as different, and this is the main focus of our discussion below. The process of globalization is often portrayed as primarily an economic phenomenon, and much is made of the role of transnational corporations, whose operations stretch across national borders, influencing global production processes and the international division of labour. Others point to the electronic integration of global financial markets and the enormous volume of global capital flows, along with the unprecedented scope of world trade, involving a much broader range of goods and services than ever before. As we will see, contemporary globalization is better viewed as the coming together of political, social, cultural and economic factors.

Elements of globalization

The process of globalization is closely linked to the development of information and communication technology, which has intensified the speed and scope of interactions between people around the world. Think of the 2018 football World Cup, held in Russia. Because of satellite technology, global television links, submarine communication cables, fast broadband connections and widening computer access, games could potentially be seen live by billions of people across the world. This simple example shows how globalization is embedded within the everyday routines of more people in more regions of the world, creating genuinely global shared experiences – one important prerequisite for the development of a global society.

The explosion in global communications has been facilitated by a number of important technological advances. Since the Second World War, there has been a profound transformation in the scope and intensity of telecommunication flows. Traditional telephonic communication, which depended on analogue signals sent through wires and cables with the help of mechanical crossbar switching, has been replaced by integrated systems in which vast amounts of information are compressed and digitally transferred. Cable technology has become more efficient and less expensive, and the development of fibre-optic cables has dramatically expanded the number of channels that can be carried.

The earliest transatlantic cables, laid in the 1950s, were capable of carrying fewer than 100 telephone channels, but by 1992 a single transoceanic cable could carry some 80,000 channels. In 2001, a transatlantic submarine fibre-optic cable was laid that is capable of carrying the equivalent of a staggering 9.7 million telephone channels (Atlantic Cable 2010). Today, such cables carry not just telephony but internet traffic, video and many other types of data. The spread of communications satellites orbiting the planet, beginning in the 1960s, has also been significant in expanding international communications. Today, a network of more than 200 satellites is in orbit facilitating the transfer of information around the globe, though the bulk of communication continues to be via submarine cables, which are still more reliable.

Classic studies 4.1 Immanuel Wallerstein on the modern world-system

The research problem

Many students come to sociology looking for answers to big questions. Why are some countries rich and others desperately poor? How have some previously poor countries managed to become relatively wealthy, while others have not? Such questions of global inequality and economic development underpin the work of the American historical sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein (1930–2019). In addressing these issues, Wallerstein sought to take forward Marxist theories of social change for a global age. In 1976 he helped to found the Fernand Braudel Center for the Study of Economies, Historical Systems and Civilizations at Binghamton University, New York, which became a focus for his own world-system research.

Wallerstein’s explanation

Before the 1970s, social scientists tended to discuss the world’s societies in terms of First, Second and Third worlds, based on their levels of capitalist enterprise, industrialization and urbanization. The solution to Third World ‘underdevelopment’ was therefore thought to be more capitalism, more industry and more urbanization. Wallerstein rejected this dominant way of categorizing societies, arguing instead that there is one world economy and that all the societies within it are connected by capitalist economic relationships. He described this complex intertwining of economies as the ‘modern world-system’, which was a pioneer of today’s globalization theories. His main arguments about how the world-system emerged were outlined in a three-volume work, The Modern World-System (1974, 1980, 1989), which set out his macrosociological perspective.

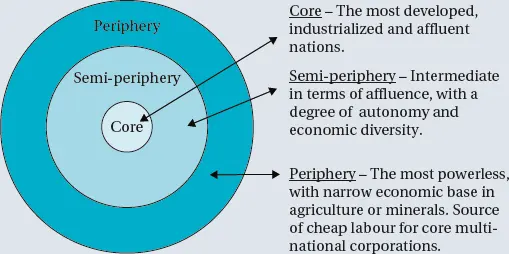

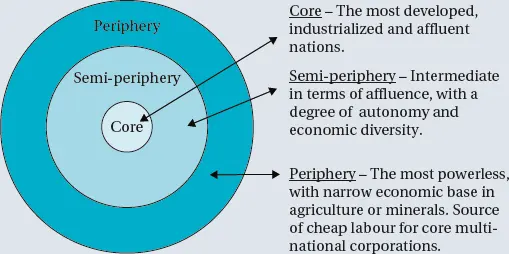

The origins of the modern world-system lie in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe, where colonialism enabled countries such as Britain, Holland and France to exploit the resources of the countries they colonized. This allowed them to accumulate capital, which was ploughed back into their economy, driving forward production and development. This global division of labour created a group of rich countries but impoverished many others, thus stunting their development. Wallerstein argues that the process produced a world-system made up of a core , a periphery and a semi-periphery (see figure 4.3). And although it is clearly possible for individual countries to move ‘up’ into the core or to drop ‘down’ into the semi-periphery and periphery, the basic structure of the modern world-system remains constant.

Wallerstein’s theory tries to explain why developing countries have found it so difficult to improve their position, but it also extends Marx’s class-based conflict theory to a global level. In global terms, the world’s periphery becomes ‘the working class’, while the core forms the exploitative ‘capitalist class’. In Marxist theory, this means that any future socialist revolution is now likely to occur in the developing countries rather than in the wealthy core, as originally forecast by Marx. This is one reason why Wallerstein’s ideas have been well received by political activists in the anti-capitalist and anti-globalization movements.

Figure 4.3 The modern world-system

Читать дальше