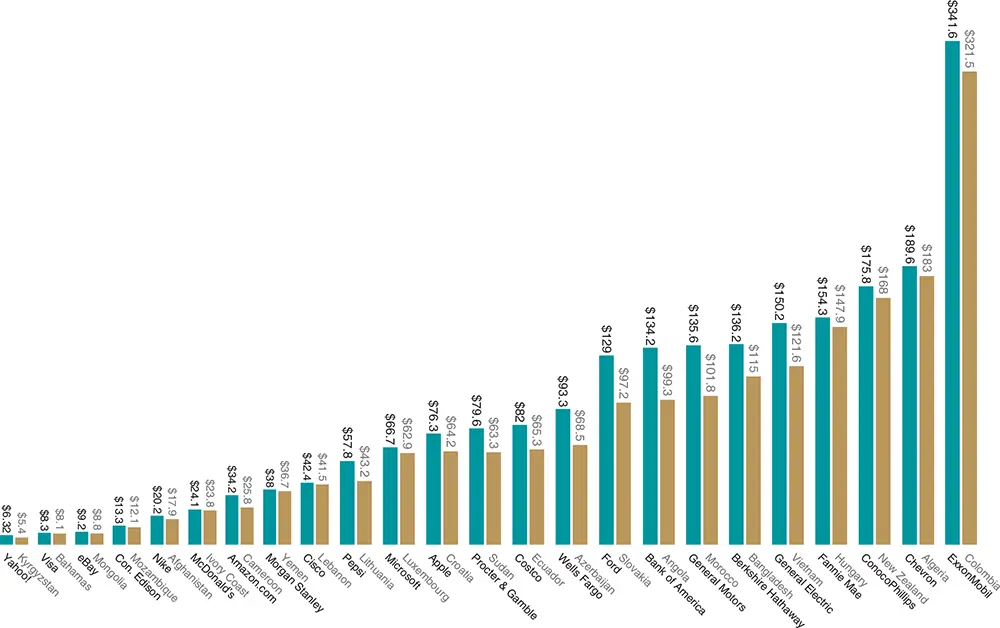

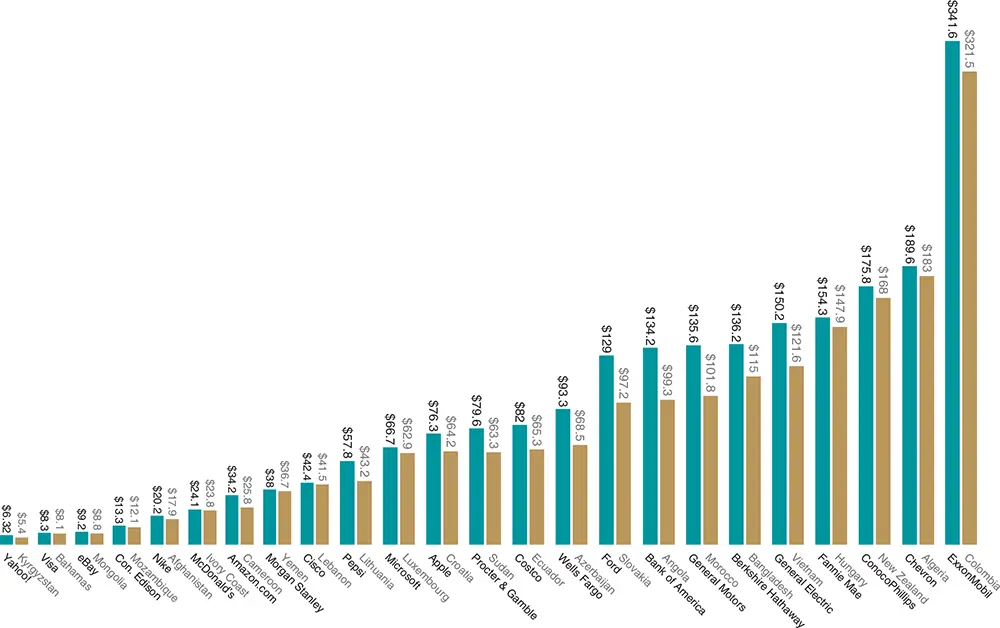

Transnational corporations lie at the heart of economic globalization, accounting for between two-thirds and three-quarters of all world trade (Kordos and Vojtovic 2016: 152). They are instrumental in the diffusion of new technologies around the globe and are major actors in financial markets (Held et al. 1999). Some 500 transnational corporations had annual sales of more than $10 billion in 2001, while only seventy-five countries could boast gross domestic products of at least that amount. In other words, the world’s leading transnational corporations are, in some respects, larger than many of the world’s countries (see figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 Top 25 US companies by sales compared with GDP of selected countries (in $US billion)

Source : Foreign Policy (2012).

USING YOUR SOCIOLOGICAL IMAGINATION

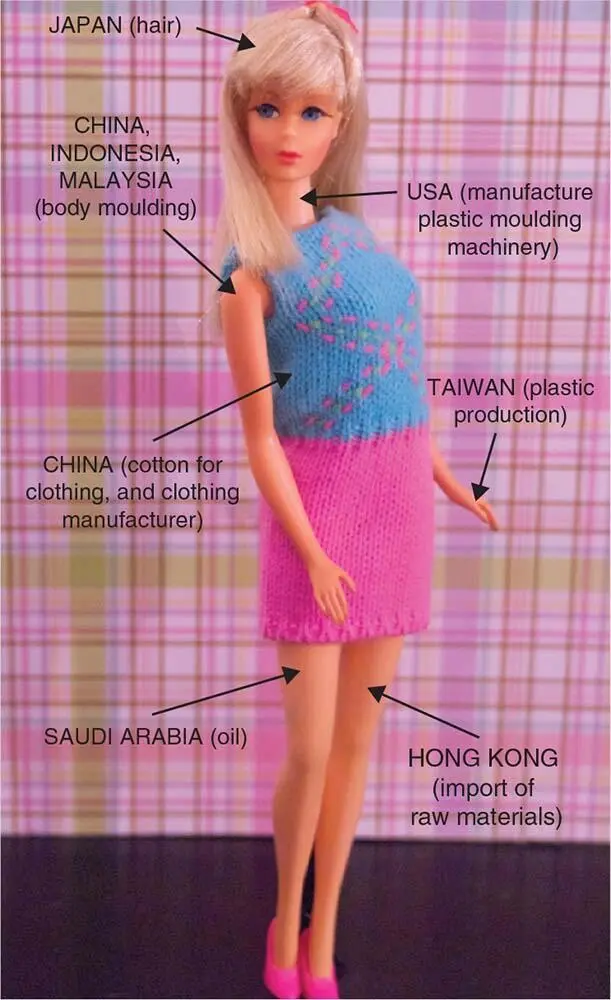

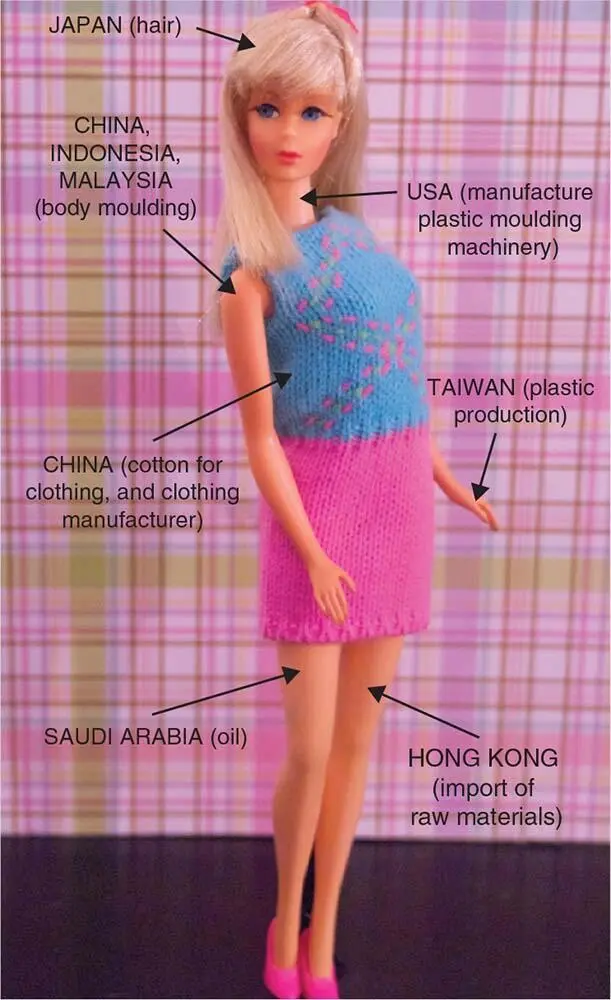

4.2 ‘Barbie’ and the development of global commodity chains

One illustration of global commodity chains is the manufacture of the Barbie doll, the most profitable toy in history. The sixty-year-old teenage doll once sold at a rate of two per second, bringing the Mattel Corporation, based in Los Angeles, USA, over $1 billion in annual revenues (Tempest 1996). Although in its early years the doll sold mainly in the USA, Europe and Japan, today Barbie can be found in more than 150 countries around the world (Dockterman 2016). To avoid relatively high labour costs, Barbie has never been manufactured in the United States (Lord 2020). The first doll was made in Japan in 1959 when wages there were lower than the US, but later manufacture moved to other low-wage countries in Asia. The manufacture of Barbie illustrates a great deal about global commodity chains.

Barbie is designed in Mattel’s California headquarters, where marketing and advertising strategies are also devised and most of the profits are made, but the physical product has always sourced its various elements from all over the world.

Tempest (1996) reported that, in the late 1990s, Barbie’s body was made from oil produced in Saudi Arabia and refined there into ethylene, which Taiwan’s Formosa Plastic Corporation converted into PVC pellets. The pellets were then shipped to one of the four Asian factories – two in southern China, one in Indonesia and one in Malaysia. The plastic mould injection machines that shape the body were made in the USA and shipped out to the factories. Barbie’s nylon hair came from Japan and her cotton dresses were made in China with Chinese cotton (the only raw material to come from the country where most of the dolls were made). Nearly all the material used in the manufacture was then shipped into Hong Kong and on to factories in China by truck. The finished dolls left by the same route, with 23,000 trucks making the daily trip between Hong Kong and southern China’s toy factories. More recently, Noah (2012: 100) argues that ‘The same pattern persists today, but the volume and technological sophistication of today’s “Made in China” products are much greater.’

As for Barbie, sales fell by 6 per cent in 2013, but by 2019 were rising again, up 12 per cent in the fourth quarter of the year (Whitten 2019). This follows diversification of the traditionally slim, blonde-haired, white original version. Barbie is now available in a range of skin tones and body shapes (‘petite’, ‘tall’ and a ‘curvy body’ that reflects the influence of global celebrities such as Beyoncé and Kim Kardashian) and in a variety of employmentbased outfits, including a space suit (Kumar 2019). With a live-action movie in the next stage, who would bet against Barbie appearing in the tenth edition of this book?

Barbie literally embodies global commodity chains.

What Barbie production and consumption shows us is the effectiveness of globalization in connecting the world’s economies. However, it also demonstrates the unevenness of globalization, which enables some countries to benefit at the expense of others. We cannot assume that global commodity chains will inevitably promote rapid economic development across the chain of societies involved.

Is global Barbie an example of the positive potential of globalization to provide work and a wage to those outside the rich, developed world? Consider which social groups, organizations and countries stand to benefit most from the operation of the doll’s global commodity chain.

The argument that manufacturing industry is increasingly globalized is often expressed in terms of global commodity chains – worldwide networks of labour and production processes yielding a finished product. Such networks consist of production activities that form a tightly interlocked ‘chain’ from raw materials to the final consumer (Appelbaum and Christerson 1997). China, for instance, has moved from the position of a low- to a middle-income country because of its role as an exporter of manufactured goods. By 2018, China and India provided the largest shares of total commodity chain employment, at 43.4 per cent and 15.8 per cent respectively, with the USA being the main export destination (Suwandi et al. 2019). Yet the most profitable activities in the commodity chain – engineering, design and advertising – remain mainly in high-income countries, while the least profitable aspects, such as factory production, occur in low-income ones, thus reproducing rather than challenging global inequality.

Globalization is not simply the product of technological developments and the growth of transnational capitalist networks; it is also linked to political change. One key shift was the collapse of communism in a series of dramatic revolutions in Eastern Europe from 1989, culminating in the dissolution of the Soviet Union itself in 1991. This marked the effective end of the so-called Cold War. Since then, countries in the former Soviet bloc – including Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, the Baltic states, the states of the Caucasus and Central Asia, and elsewhere – have moved towards Western-style political and economic systems. The collapse of communism was hastened by, but also furthered, the process of globalization, as the centrally planned economies and communist parties’ ideological and cultural control were ultimately unable to survive in the emerging era of global media and a more electronically integrated world economy.

A second political development has been the growth of international and regional mechanisms of government, bringing nation-states together and pushing international relations in the direction of new forms of global governance. For example, McGrew (2020: 22) notes that ‘Today there are over 260 permanent intergovernmental organizations constituting a system of global governance, with the United Nations at its institutional core.’ The United Nations and the European Union are perhaps the most prominent examples of nation-states being brought together in common political forums. The UN achieves this through the association of individual nation-states, while the EU has pioneered forms of transnational governance in which a degree of national sovereignty is relinquished by states in order to gain the benefits of membership. Governments of EU states are bound by directives, regulations and court judgements from common EU bodies, but they also reap the economic, social and political benefits from participation in the EU single market.

Читать дальше