International governmental organizations (IGOs) and international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) are also important forms of an increasingly global politics. IGOs are bodies established by participating governments and given responsibility for regulating or overseeing a particular domain of activity that is transnational in scope. The International Telegraph Union, founded in 1865, was the first, but since then a large number of similar bodies have been created, regulating issues from civil aviation to broadcasting and the disposal of hazardous waste. They include the United Nations (UN), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

INGOs differ from IGOs in that they are not affiliated with government institutions. They are independent and work alongside governmental bodies in making policy decisions and addressing international issues. Some of the best known – such as Greenpeace, Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders), the Red Cross/Red Crescent and Amnesty International – are involved in environmental protection, healthcare and the monitoring of human rights. But the activities of thousands of lesser-known groups also link countries and local communities together.

What has emerged from the increasing range of transnational political bodies is essentially a form of political globalization, where the central issues are not related purely to national self-interest but take in international and global issues and problems. Modelski and Devezas (2007) see this as essentially the evolution of a global politics, the shape of which has yet to be determined.

Structuring the globalization debate

Accounts of globalization in sociology have been seen as three broad tendencies or ‘waves’ which ran throughout the 1990s and into the early twenty-first century. And, though there has been much work on specific aspects of globalization since then, the structure of the debate continues to flow across these basic positions. There is an additional approach to globalization, which Martell (2017: 14) calls a ‘fourth wave’, based on forms of discourse analysis that study existing narratives of globalization and the way they frame, discuss and shape globalization itself (Cameron and Palan 2004; Fairclough 2006). However, while the majority of studies agree that important material changes are taking place internationally, they disagree on whether it is accurate or valid to bundle these together under the umbrella of globalization. Because of this, and for reasons of space, in this section we concentrate on the first three waves.

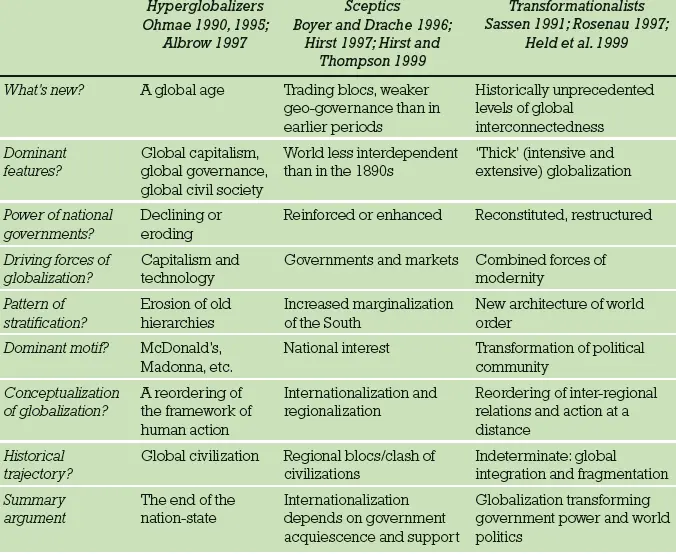

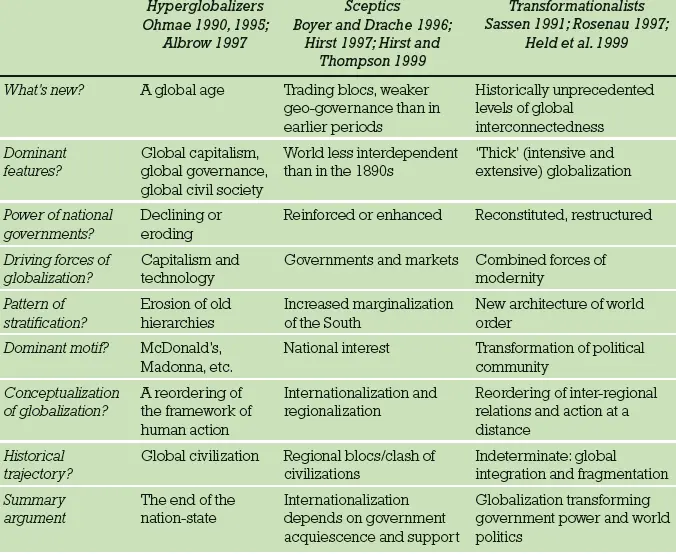

An influential discussion of the three main positions in the debate is that of David Held and colleagues (1999). This presents three schools of thought – hyperglobalizers, sceptics and transformationalists – which are summarized in table 4.4. The authors cited for each school are selected because their work contains some of the key arguments that define that school’s approach. We will take each wave in turn.

First-wave hyperglobalizers view globalization as a very real, ongoing process with wide-ranging consequences that is producing a new global order, swept along by powerful flows of cross-border trade and production. Ohmae (1990, 1995) sees globalization leading to a ‘borderless world’ in which market forces are more powerful than national governments. A large part of this argument rests on the idea that nation-states are losing the power to control their own destiny. Rodrik (2011) argues that individual countries no longer oversee their economies because of the vast growth in world trade, while governments are increasingly unable to exercise authority over volatile world financial markets, investment decisions, increasing migration, environmental dangers or terrorist networks. Citizens also recognize that politicians have limited ability to address these problems and, as a result, lose faith in existing systems of national governance.

The hyperglobalization argument suggests that national governments are caught in a pincer movement, being challenged from above (by regional and international institutions, such as the European Union and the World Trade Organization) and from below (by international protest movements, global terrorism and a lot of talk about something that is quite longstanding, while many of the changes described are not ‘global’ at all (Hirst et al., 2009). For example, current levels of economic interdependence are not unprecedented. Nineteenth-century statistics on world trade and investment lead some to argue that contemporary globalization differs from the past only in the intensity of interactions between nation-states. If so, then it is more accurate to talk of ‘internationalization’ rather than globalization, and this also preserves the idea that nation-states have been and are likely to continue as the central political actors. For instance, Thompson (in Hirst et al., 2009) argues that, during the 2008 ‘global’ financial crisis, it was actually national governments and citizens’ initiatives). Taken together, these shifts signal the dawning of an age in which a global consciousness develops and the influence of national governments declines (Albrow 1997). One consequence is that sociologists will have to be weaned off the concept of ‘society’, which has conventionally meant the bounded nation-state. Urry (2000) has argued that sociology needs to develop a ‘post-societal’ agenda rooted in the study of global networks and multiple flows across national borders.

Table 4.4 Conceptualizing globalization: three tendencies/waves

Source : Adapted from Held et al. (1999: 10).

Second-wave arguments are rooted in the sceptical view that globalization is overstated. Most globalization theories, say sceptics, amount to regulatory systems that stepped in as ‘lender-of-last-resort’ to protect their own economies. National governments remain key players because they are involved in regulating and coordinating economic activity, and some are driving through trade agreements and policies to promote economic liberalization.

Sceptics agree that there may be more contact between countries than in previous eras, but there is insufficient integration to constitute a single, global economy. This is because the bulk of trade occurs within just three regional groups – Europe, Japan/East Asia and North America – rather than in a genuinely global context. The countries of the European Union, for example, trade predominantly among themselves, and the same is true of the other regional groups, thereby invalidating the concept of a global economy (Hirst 1997).

As a result, many sceptics focus on processes of regionalization within the world economy, including the emergence of regional financial and trading blocs. Indeed, the growth of regionalization is evidence that the world economy has become less rather than more integrated (Boyer and Drache 1996; Hirst et al. 2009). Compared with the patterns of trade that prevailed a century ago, the world economy is actually less global in its geographical scope and more concentrated in intense pockets of activity. In this sense, hyperglobalizers are just misreading the historical evidence.

Transformationalists take a position somewhere between those of sceptics and hyperglobalizers, contending that globalization is breaking down established boundaries between the internal and the external, the international and the domestic. Yet many older patterns remain, and national governments retain a good deal of power and influence. Rather than losing sovereignty, nation-states are restructuring and pooling it in response to new forms of economic and social organization that are non-territorial (Thomas 2007). These include corporations, social movements and international bodies. The transformationalist argument is that we no longer live in a state-centric world, but states are adopting a more active, outward-looking stance towards governance under complex conditions of globalization (Rosenau 1997).

Читать дальше