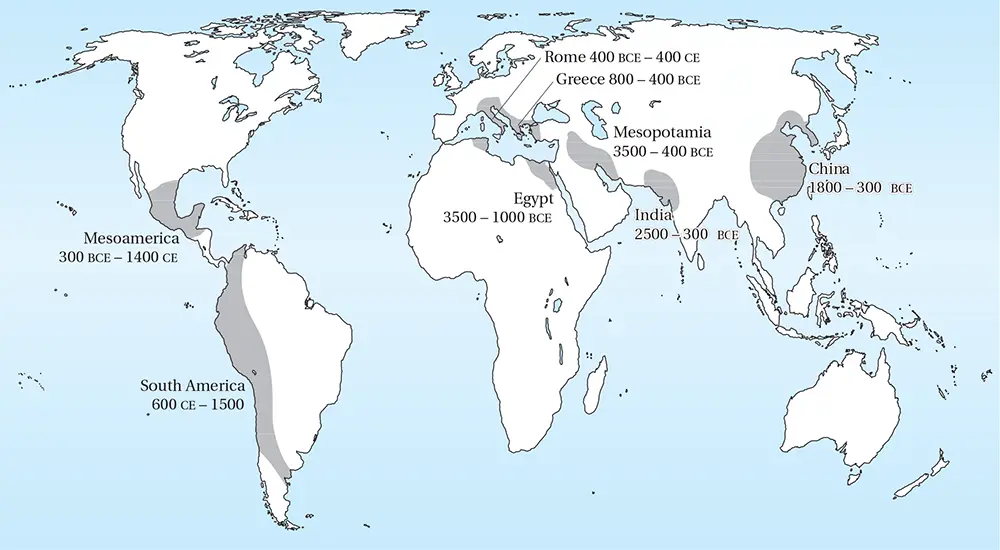

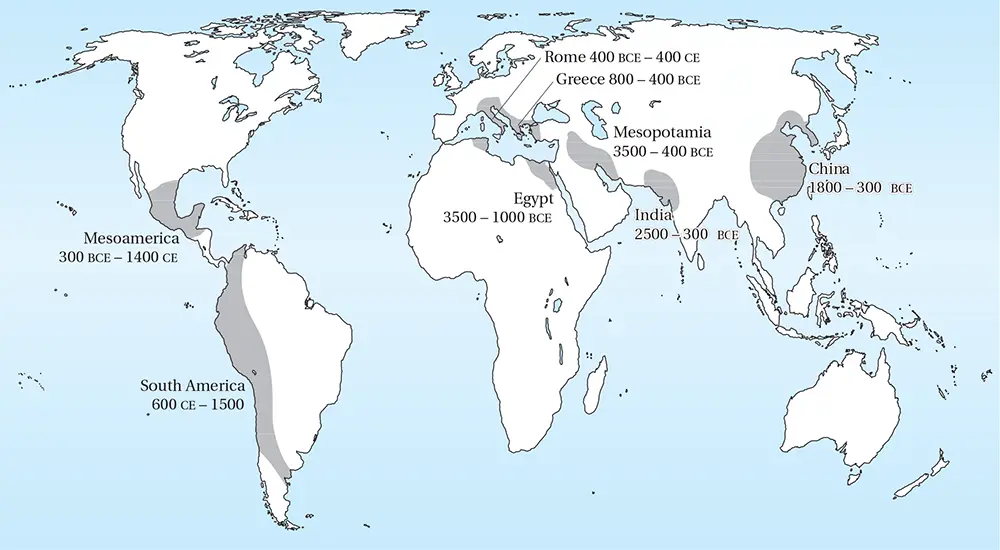

The emergence of large-scale civilizations and empires shows that the very long-term process of human expansion has long involved invasion, war and violent conquest every bit as much as cooperation and mutual exchange (Mennell 1996). By the dawn of the industrial era in 1750, humans had already settled in all parts of the globe, though the world population was still relatively small, at 771 million (Livi Bacci 2012: 25). But this was about to change in a radical way.

The transformation of societies

What happened to transform types of society that had existed for the majority of human history? A large part of the answer is industrialization – which refers to the emergence of machine production, based on the widespread use of inanimate power resources such as steam and electricity to replace humans and animals wherever possible. The industrial societies (often called ‘modern’ or ‘developed’ societies) are very different from all previous types of social order, and their spread has had genuinely revolutionary consequences.

Figure 4.2 Civilizations in the ancient world

Modernity and industrial technology

In even the most advanced of traditional civilizations, the relatively low level of technological development permitted only a small minority to escape agricultural work. Modern technology has transformed the way of life enjoyed by a very large proportion of the human population. As the economic historian David Landes (2003: 5) observes:

Modern technology produces not only more, faster; it turns out objects that could not have been produced under any circumstances by the craft methods of yesterday. The best Indian hand-spinner could not turn out yarn so fine and regular as that of the [spinning] mule; all the forges in eighteenth-century Christendom could not have produced steel sheets so large, smooth and homogeneous as those of a modern strip mill. Most important, modern technology has created things that could scarcely have been conceived in the pre-industrial era: the camera, the motor car, the airplane, the whole array of electronic devices from the radio to the high-speed computer, the nuclear power plant, and so on almost ad infinitum.

Even so, the continuing existence of gross global inequalities means that this technological development is not shared equally across the world’s societies.

The modes of life and social institutions characteristic of the modern world are radically different from those of even the recent past, and over a period of less than three centuries – a sliver of time in human history – people have shifted away from ways of life that endured for many thousands of years. For example, a large majority of the employed population now work in services, factories, offices and shops rather than agriculture, while the largest cities are denser and larger than any urban settlements found in traditional civilizations.

The role of cities in the new global order is discussed in chapter 13, ‘Cities and Urban Life’.

In traditional civilizations, political authorities (monarchs and emperors) had little direct influence on the customs and habits of most of their subjects, who lived in fairly self-contained local villages. With industrialization, transportation and communication became much more rapid, making for a more integrated ‘national’ community. The industrial societies were the first nation-states to come into existence. Nation-states are political communities, divided from each other by clearly delimited borders rather than the vague frontier areas that separated traditional states. States have extensive powers over many aspects of citizens’ lives, framing laws that apply to all those within their borders. Virtually all societies in the world today are nation-states of this kind.

Nation-states are discussed more extensively in chapter 20, ‘Politics, Government and Social Movements’, and chapter 21, ‘Nations, War and Terrorism’.

Industrial technology has by no means been limited to peaceful economic development. From the earliest phases, production has been put to military use, radically altering how societies wage war, creating weaponry and military organizations far more advanced than in earlier cultures. Together, economic strength, political cohesion and military superiority account for the spread of ‘Western’ ways of life across the world over the last 250 years. Once again we have to acknowledge that globalization is not simply about trade but is a process that has often been characterized by wars, violence, conquest and inequality (see chapter 21, ‘Nations, War and Terrorism’).

Which three aspects of modern, industrialized countries that make them radically different from earlier societies would you pick out as the most significant?

Classifying the world’s societies

Classifying countries and regions into groups according to criteria of similarity and difference is always contentious, as all such schemes are likely, or may be perceived, to contain value judgements. For example, after the Second World War, and with the developing Cold War between the superpowers of the Soviet Union and the USA, the three worlds model was widely used in academic studies. In this model, the First World included the industrialized countries such as the USA, Germany and the UK; the communist countries of the Soviet Union (USSR) and Eastern Europe made up the Second World ; and the non-industrial countries with relatively low average incomes made up the Third World (see chapter 6, ‘Global Inequality’, for a discussion of the political origins of concept of the Third World).

Although presented as a neutral classification, it is hard to use these terms without appearing to imply that the First World is somehow superior to the Second and the Second is superior to the Third. In short, this scheme was adopted by scholars from the First World, who viewed their own societies as the norm towards which all others would or should strive. The collapse of Eastern European communism after 1989 and rapid industrialization in some Third World countries made this model less empirically adequate, and few, if any, social scientists use this scheme uncritically today.

An alternative scheme that is still widely used today is the simple, perhaps overly simple, distinction between developed and developing countries. Countries that have undergone a thorough process of industrialization and have high levels of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, including Australia, Norway and France, fall within the category of developed countries. On the other hand, developing countries have mostly been exploited and underdeveloped by colonial regimes and consequently are less industrialized, have lower levels of GDP per capita, and are undergoing a long-term process of economic improvement. Niger, Chad, Burundi and Mali fall into this category, for example (UNDP 2019b: 300–3). This basic classification has long been used by the UN and those working in the sub-field of ‘development studies’, though it does not claim to be based on widely agreed criteria. Instead it is designed to enable the collection of statistical information which allows for international comparisons, which in turn facilitates interventions aimed at improving the life chances of people in developing countries.

Читать дальше