1 ...6 7 8 10 11 12 ...15 (Figure courtesy of Dr Paul Rea and Caroline Morris, University of Glasgow.)

The anterior fibres of this muscle, which form its major bulk, are mainly vertical and elevators of the mandible. Progressing posteriorly along the middle and posterior parts of the muscle, the fibres become increasingly oblique and the posterior fibres are almost horizontal. The anterior fibres are elevators of the mandible. The posterior fibres retrude the mandible.

In parafunction, this muscle becomes symptomatic and painful, usually in the anterior part of the temple, in patients who perform the parafunctional activity of bruxism or tooth grinding.

This muscle is accessible to digital palpation only over its origin. It is usually the anterior vertical fibres that are tender to digital palpation, although the posterior horizontal fibres can on occasion also be found to be tender. The insertion of this muscle is not accessible for digital palpation ( Chapter 3).

The lateral pterygoid muscle

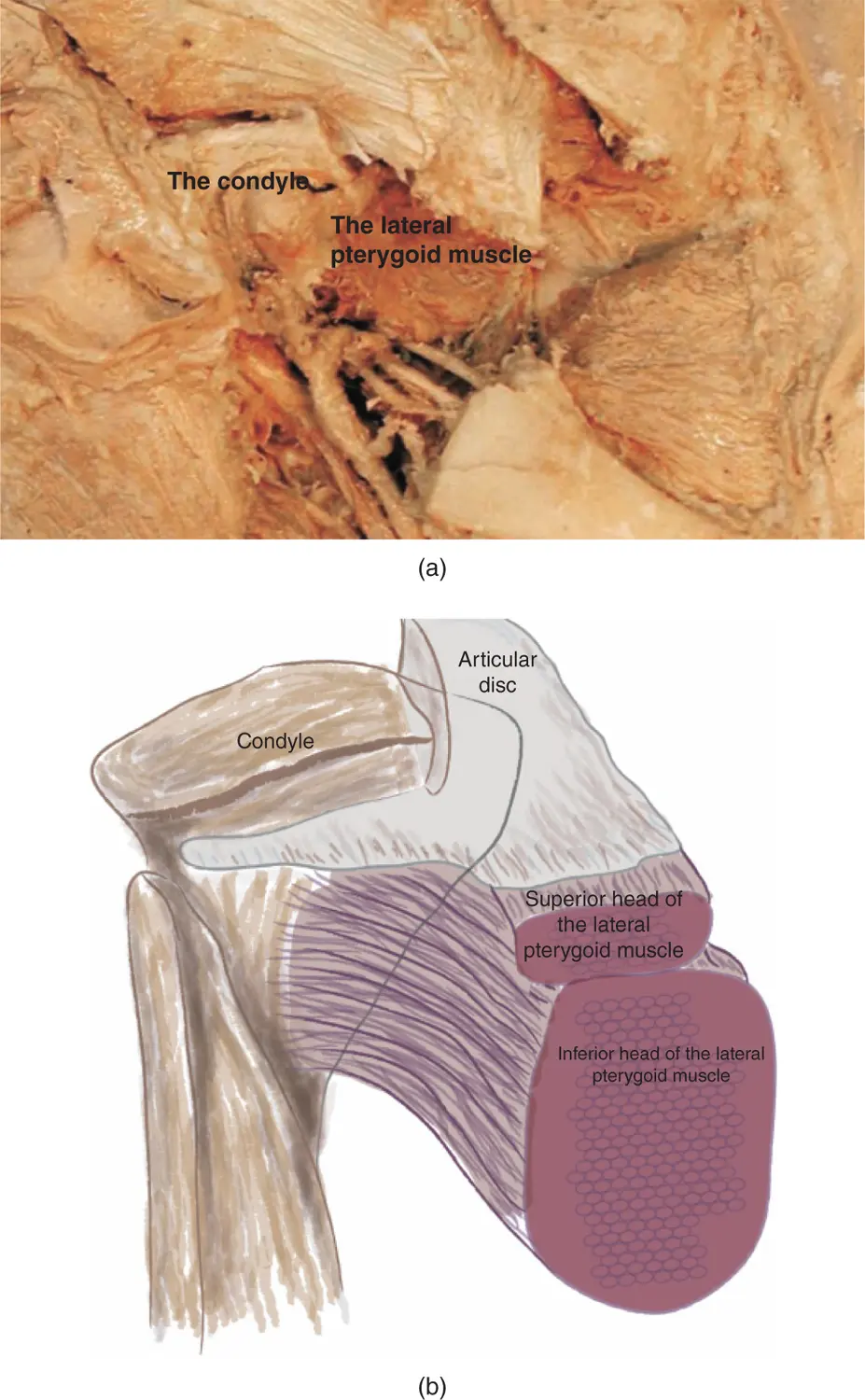

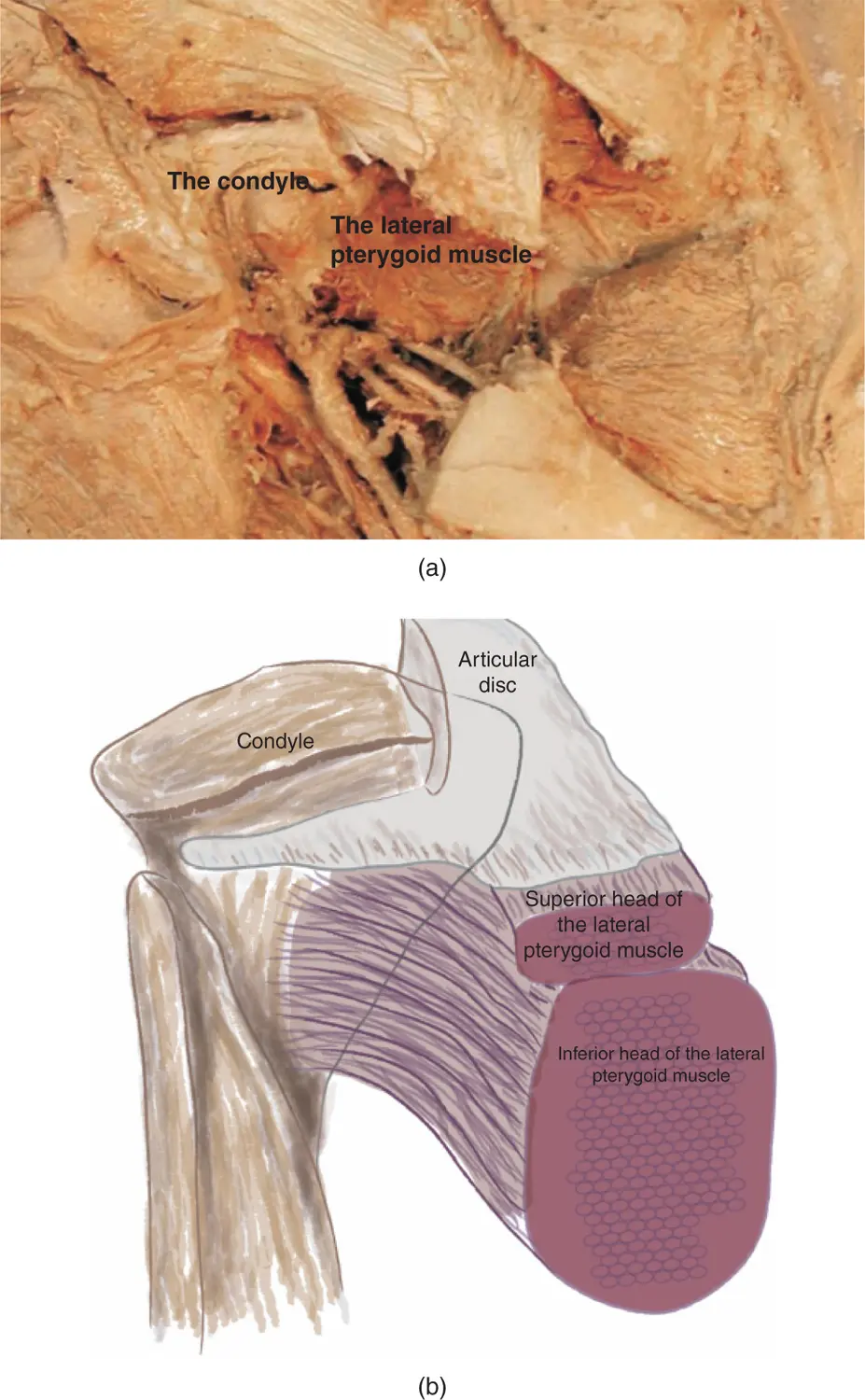

Controversy still surrounds this muscle as to whether it has one single or two separate heads and one single or two different actions. It is, however, generally regarded that the lateral pterygoid muscle has two separate parts, these being the inferior belly and the superior belly usually referred to as the superior and inferior pterygoids. The inferior pterygoid originates in the lateral surface of the lateral pterygoid plate and inserts into a fossa in the anterior part of the head of the condyle. The superior pterygoid originates from the infratemporal surface of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone and inserts into the anterior part of the capsule and intra‐articular disc. It also has a small attachment into the fossa in the anterior part of the head of the condyle ( Figure 2.12).

Figure 2.12The lateral pterygoid muscle (a) (Courtesy of Dr Paul Rea and Caroline Morris, University of Glasgow.) (b) Schematic representation illustrating the insertion of the superior and inferior heads of the lateral pterygoid muscle (capsule cut away).

The function of this muscle is thought to be twofold: first, it assists in opening the mouth and in depression of the mandible; second it assists in protrusion of the mandible and lateral movements. In addition, this muscle is thought to be important in stabilisation of the condyle/intra‐articular disc/fossa assembly.

There is controversy about the precise action of the pterygoid muscle. However, it is clear that this is an important muscle in protrusion of the mandible, which occurs when both right and left muscles act synchronously. When the pterygoid muscle on one side contracts, the effect is to pull the mandible laterally towards that side.

In parafunction, there appears to be increased activity in both superior and inferior pterygoids which appears to cause pain referred to the preauricular region when the muscle is examined against resistance. In addition, it is thought possible that sustained tonic contraction of the superior pterygoid muscle can be a factor in anteromedial displacement of the intra‐articular disc.

This muscle is not accessible to digital palpation and should be examined against resistance. The patient should be asked to open the mouth to a certain point; the operator's hand is then placed under the chin and resistance is applied by the examiner. If there is lateral pterygoid tenderness discomfort will be felt in the preauricular region. In addition, this muscle can be examined by resisting lateral movements. The patient should slide the jaw across to one side and the operator applies resistance to this lateral movement. If there is lateral pterygoid tenderness, pain in the contralateral side to the pressure will be elicited ( Chapter 3).

This muscle arises from the medial surface of the lateral pterygoid plate and the lateral aspect of the medial pterygoid plate and inserts into the angle of the mandible on the medial surface opposite the insertion of the masseter ( Figure 2.13).

Figure 2.13Medial pterygoid showing ramus of mandible sectioned: medial pterygoid muscle.

(Figure courtesy of Dr Paul Rea and Caroline Morris, University of Glasgow.)

The action of this muscle is elevation of the mandible, but it also assists in protrusion and lateral excursions of the mandible.

This is not a muscle that can be reliably examined clinically so the effect of parafunction on the muscle is just conjecture.

The medial pterygoid muscle is not accessible for manual or digital palpation.

These are many muscles including the digastric, mylohyoid, geniohyoid, and stylohyoid muscles ( Figure 2.14).

Figure 2.14Cervical muscles.

(Figure courtesy of Dr Paul Rea and Caroline Morris, University of Glasgow.)

The two muscles in this group that mainly merit consideration are the digastric and mylohyoid muscles. The digastric muscle has two separate parts: an anterior and posterior belly; the two bellies have quite different actions. They are connected by an intermediate tendon that runs through a fibrous sling on the hyoid bone.

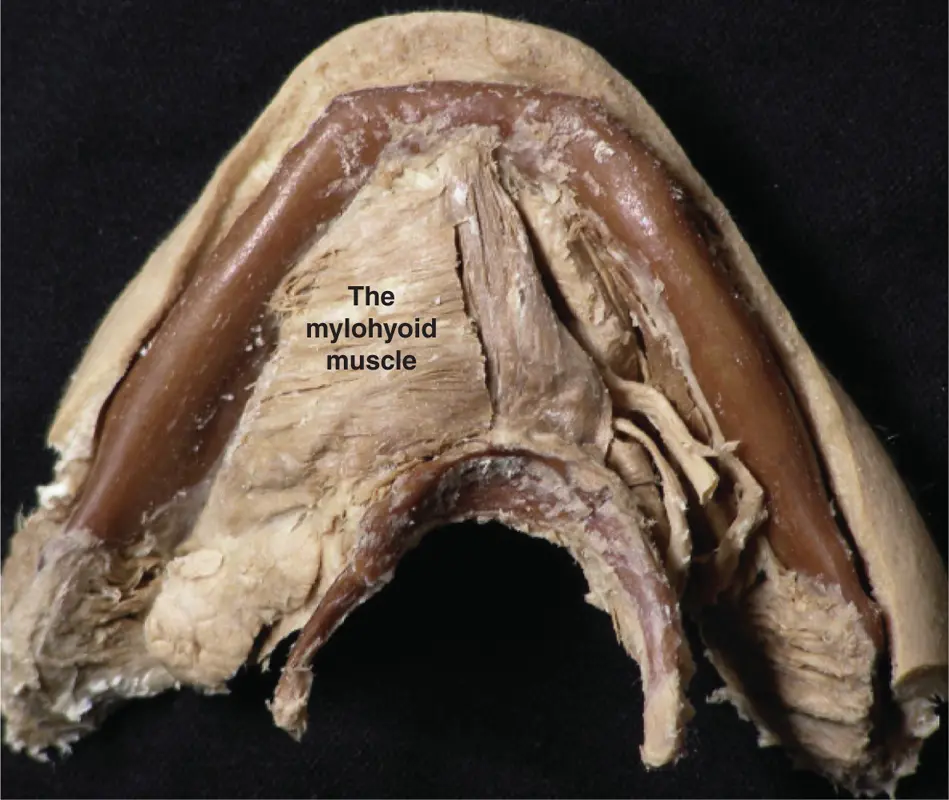

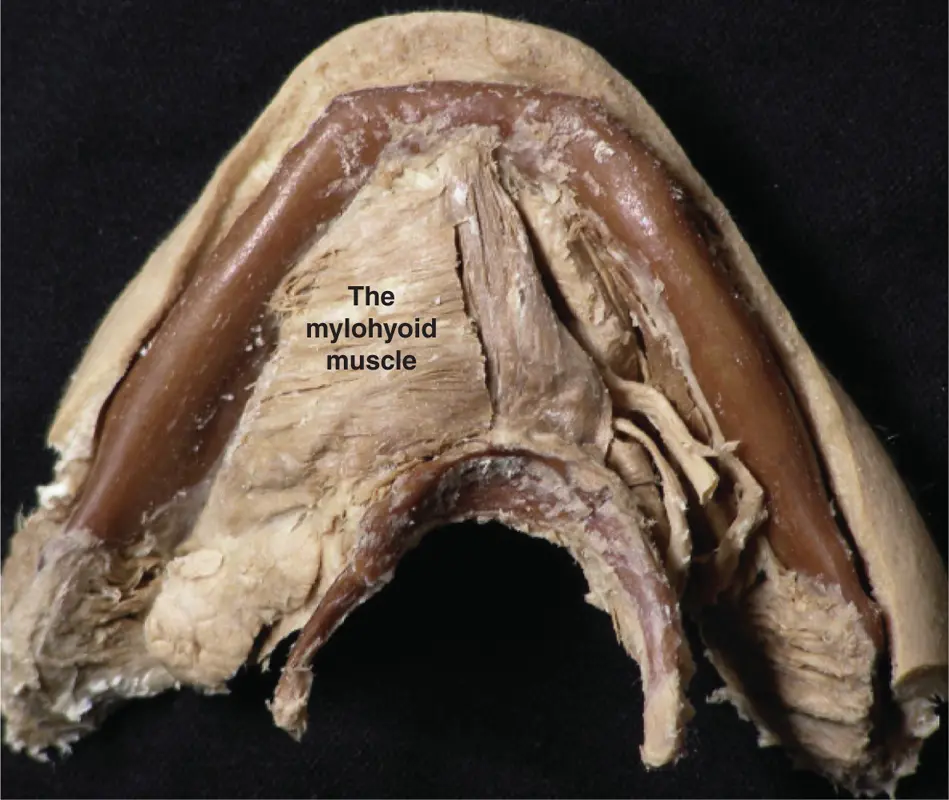

The mylohyoid muscle is a thin sheet of muscle arising on the inner aspect of the mandible from the whole length of the mylohyoid line. The two halves of this muscle meet in a median raphe, which inserts into the body of the hyoid bone. This muscle forms the floor of the mouth, separates the submandibular and sublingual regions, and is unattached posteriorly ( Figure 2.15).

Figure 2.15The mylohyoid muscle.

(Figure courtesy of Dr Paul Rea and Caroline Morris, University of Glasgow.)

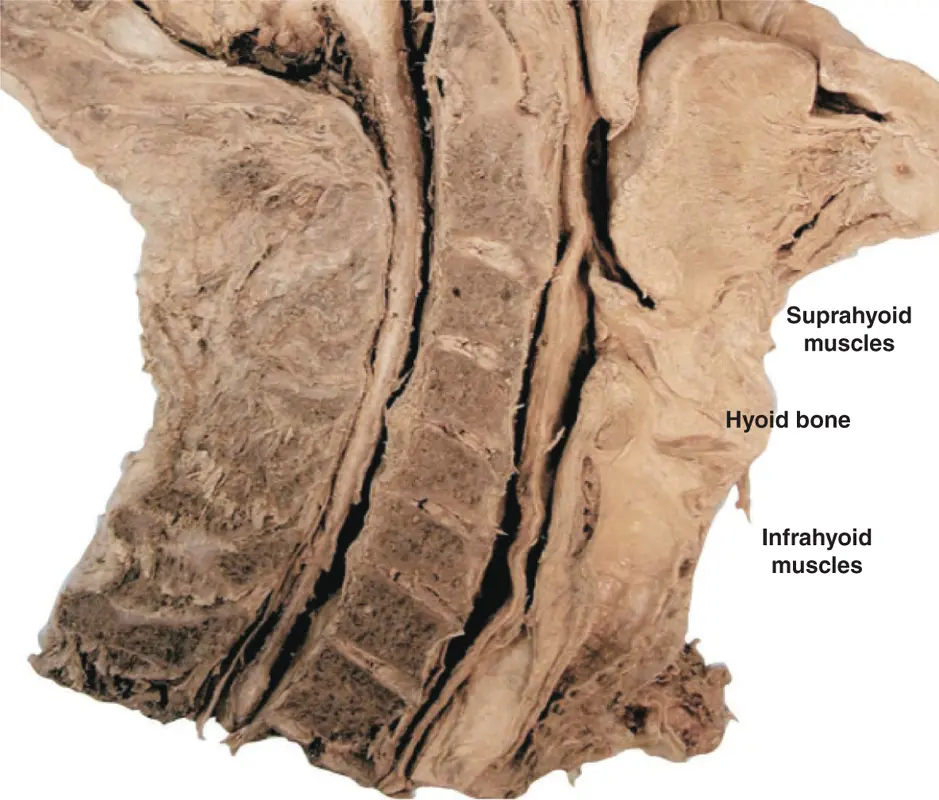

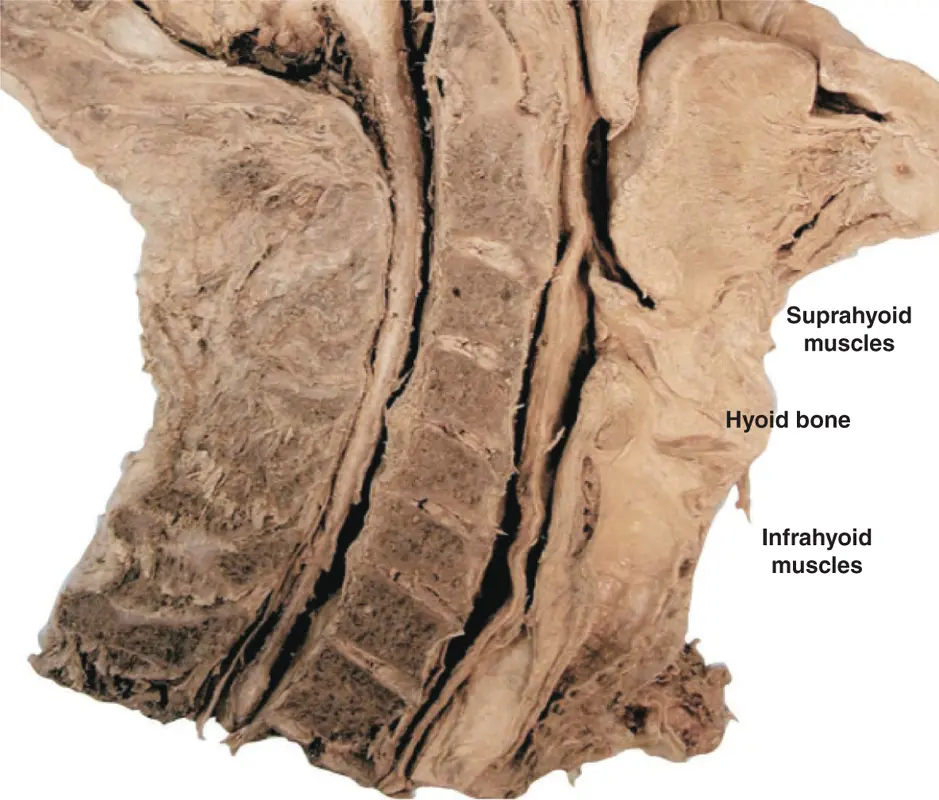

The suprahyoid muscles raise the hyoid bone and the larynx. They can also depress the mandible together with the tongue and the floor of the mouth, but only when the infrahyoid muscles stabilise the hyoid bone. The posterior belly of the digastric is, in addition one of the retruding muscles of the mandible.

This group of muscles also acts to depress the hyoid bone and larynx during swallowing. The infrahyoid and suprahyoid muscles always contract bilaterally ( Figure 2.16).

Figure 2.16The infrahyoid and suprahyoid muscles.

(Courtesy of Dr Paul Rea and Caroline Morris, University of Glasgow.)

There is little evidence to directly link the suprahyoid muscles to parafunctional symptoms apart from the digastric muscle. This muscle is found to be tender either behind the ascending ramus of the mandible or in the submandibular region in patients who have a parafunctional bruxist habit, which they perform on their anterior teeth.

Читать дальше

![John Bruce - The Lettsomian Lectures on Diseases and Disorders of the Heart and Arteries in Middle and Advanced Life [1900-1901]](/books/749387/john-bruce-the-lettsomian-lectures-on-diseases-and-disorders-of-the-heart-and-arteries-in-middle-and-advanced-life-1900-1901-thumb.webp)