This varying thickness of the bands in the disc is significant when considering the functional anatomy of the joint. The meniscus is flexible and able to alter shape to concave or convex during forward movement of the condyle, because of the thinner intermediate zone between the two thicker anterior and posterior zones.

In the “at rest” mandibular position, the condyle is separated from the temporal bone by the thick posterior band. As the head of the condyle moves forward towards the articular eminence, it is separated from the temporal bone by the thinner intermediate zone and, as anterior movement progresses, the head of the condyle continues to move forwards until it is resting on the thicker but narrow anterior band.

During mouth opening, the disc moves forwards but not to the same extent or with the same speed as the head of the condyle. The forward movement of the meniscus is permitted by the loose fibroelastic tissue of the bilaminar zone, which is stretchable to 7–10 mm. In addition, the structures of the bilaminar zone are ideally suited to filling the void of the vacated glenoid fossa when the condyle is in a protrusive position.

The non‐elastic lower band attached to the posterior neck of the condyle contributes to the return of the meniscus during retrusion of the mandible. This is helped by the elastic recoil of the upper attachment.

The disc acts as a ‘shock absorber’ during masticatory function. The central part of the disc is mainly avascular and depends on nutrition from diffusion from the synovial fluid. A rich vascular plexus is, however, present in the posterior part of the bilaminar zone which is mainly supplied from the deep auricular artery, a branch of the internal maxillary artery. Although the central part of the meniscus is poorly innervated, the bilaminar zone has a dense innervation from a branch of the auricular temporal nerve, the masseteric nerve and the posterior deep temporal nerve.

It has been suggested that the articular disc has many functions which may include shock absorption, increasing congruity between the articular surfaces, allowing combinations of different movements at the joint, ball‐bearing action, force distribution by increasing the contact area between articular surfaces, providing stability during mandibular movements and playing a role in assisting joint lubrication by forming thin synovial fluid films.

The bones of the temporomandibular joint

The mandibular condyle

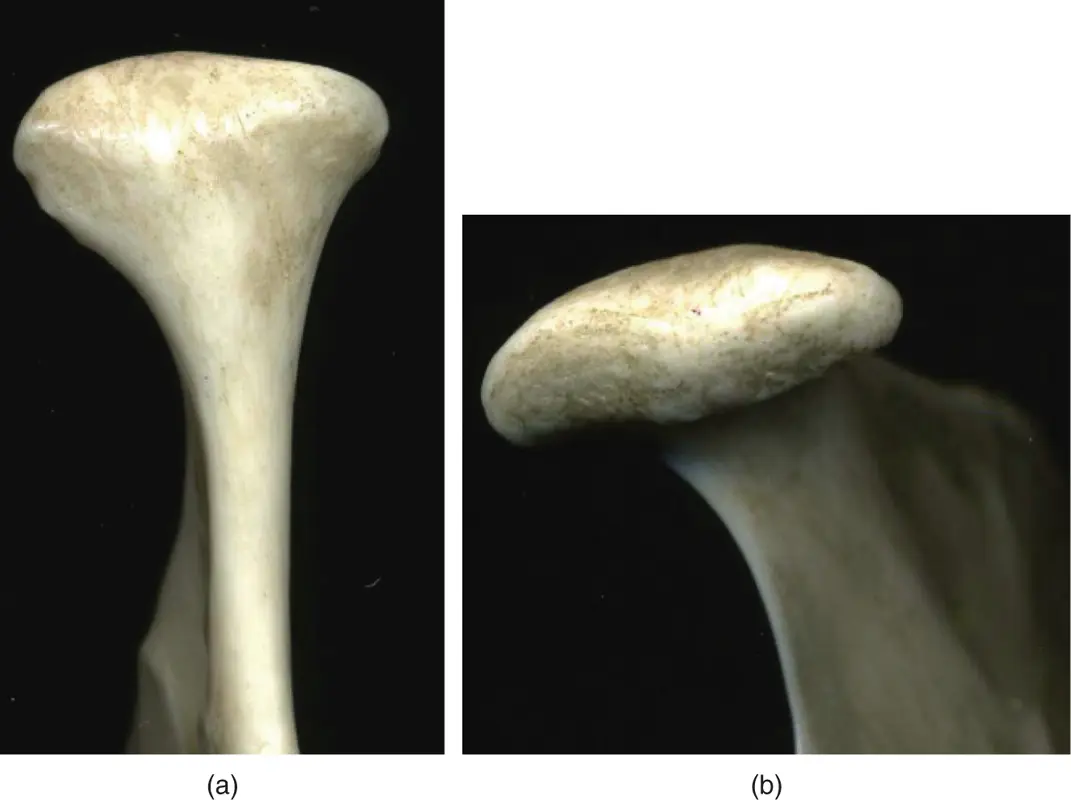

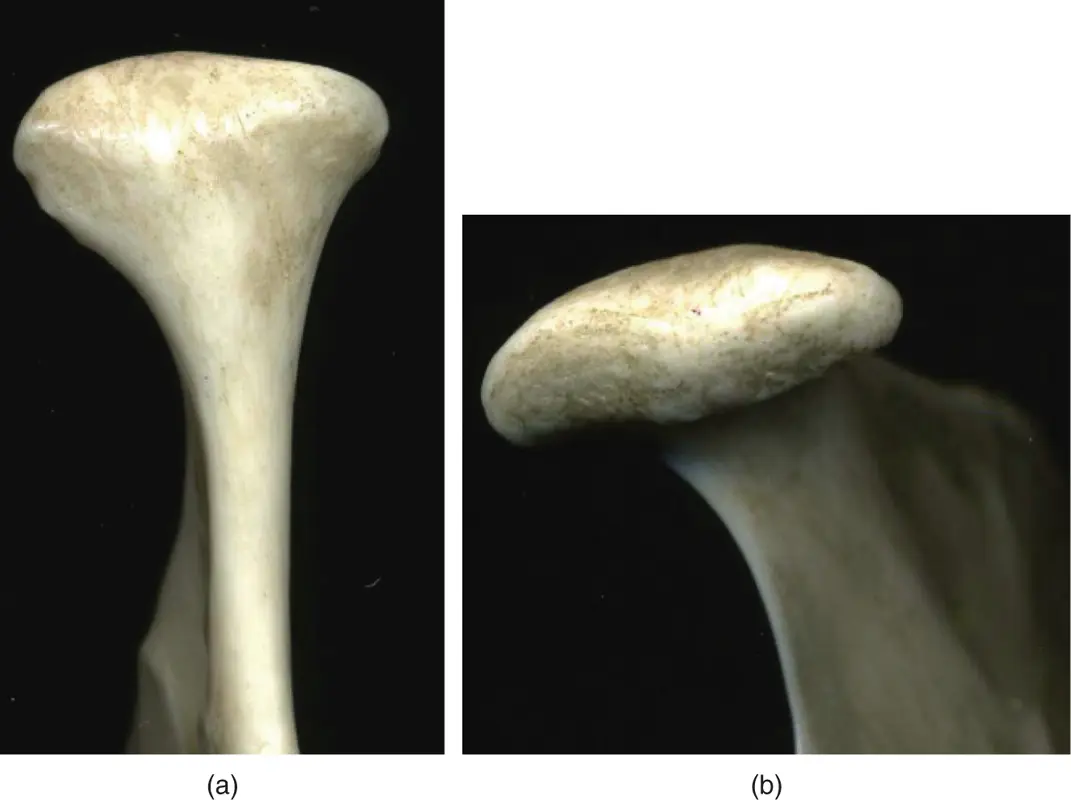

The adult mandibular condyle is roughly elliptical in shape with the largest diameter being mediolateral ( Figure 2.8). There is considerable individual variation in both condylar size and angulation to the various planes, and there are often differences between the right and left sides in an individual. The mediolateral dimension varies between 13 and 25 mm and the anteroposterior dimension varies between 6 and 16 mm. The mediolateral angulation to the transverse plane is between 15° and 33° and from 0° to 48° in the horizontal plane. These dimensions vary not only between individuals but between the right and left sides in an individual.

Figure 2.8The mandibular condyle.

(M. Ziad Al‐Ani, Robin J.M. Gray.)

The articular surface of the temporal bone consists, posteriorly, of the concavity of the glenoid fossa and, anteriorly, of the convexity of the articular eminence; it extends from the anterior margin of the squamotympanic fissure to the margin of the articular eminence. The roof of this fossa is very thin, indicating that this part is not a load‐bearing area. Anteriorly, however, the articular eminence is thicker and this area, together with the disc, may be the area that bears most of the load during function ( Figure 2.9).

Figure 2.9The articular part of the temporal bone.

(M. Ziad Al‐Ani, Robin J.M. Gray.)

This arises from the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. The auriculotemporal nerve innervates most of the TMJ mainly anterolaterally and small branches of the masseteric and deep temporal nerves supply the posterior aspect.

Vascular supply to the TMJ

Vascular supply to the TMJ is from the external carotid artery via the internal maxillary artery and the superficial temporal artery.

Mandibular (jaw/masticatory) muscles

The jaw muscles form another component of the articulatory system.

The muscles commonly symptomatic in temporomandibular disorders that are accessible for clinical examination are the masseter, temporalis, lateral pterygoid, and digastric muscles. Other muscles involved but not comprising part of the routine clinical examination are the medial pterygoid, mylohyoid, suprahyoid, infrahyoid, and cervical muscles.

This muscle originates from the anterior two‐thirds of the zygomatic arch and extends obliquely downwards to its insertion over the lateral surface of the angle of the mandible ( Figure 2.10).

Figure 2.10The masseter muscle.

(Figure courtesy of Dr Paul Rea and Caroline Morris, University of Glasgow.)

There are two portions to this muscle: the superficial and the deep. The superficial masseter is one of the primary elevator muscles of the mandible during jaw closure, but, as some of its fibres are angled anteriorly, it also assists in protrusion of the mandible. The deep portion is one of the main elevators of the mandible but, as some of its fibres run posteriorly, it is active in retrusion of the mandible.

This muscle is active during clenching of the teeth and is frequently found to be tender at its origin and less frequently at its insertion.

The muscle is examined bimanually with one finger inside and one finger outside the mouth to palpate the origin and insertion of this muscle. It is usually tender where it inserts into bone ( Chapter 3).

This is a large, broad, fan‐shaped muscle that has its origin in the temporal fossa between the superior and inferior temporal lines, which run across the parietal bone, temporal bone, and greater wing of the sphenoid, extending forwards to the temporal surface of the frontal bone. The fibres of this muscle run in various directions and converge into a tendinous insertion which runs under the zygomatic arch and inserts into the coronoid process and anterior border of the ascending ramus of the mandible ( Figure 2.11).

Figure 2.11The temporalis muscle.

Читать дальше

![John Bruce - The Lettsomian Lectures on Diseases and Disorders of the Heart and Arteries in Middle and Advanced Life [1900-1901]](/books/749387/john-bruce-the-lettsomian-lectures-on-diseases-and-disorders-of-the-heart-and-arteries-in-middle-and-advanced-life-1900-1901-thumb.webp)