1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...40 The almost universal availability of high‐capacity and powerful desktop computers in the 1990s greatly facilitated the management of industrial hygiene programs. An abundance of industrial hygiene‐related software for record keeping, technical reference (e.g. regulations and safety data sheets [SDSs]), sampling data analysis, exhaust ventilation design, and other such industrial hygiene functions became available from commercial sources, or through professional journals, professional associations, and individual industrial hygienists. The AIHA began a Computer Applications Committee, whose mission it is to provide a forum for advancing the use of computer applications by occupational and environmental health professionals.

The science and profession of industrial hygiene became generally recognized as having an important role in industry. It was recognized generally in the 1990s that the industrial hygienist at the corporate or equivalent level should report to top management. His/her responsibility involves appropriate input whenever product, technological, operational, or process changes, or other corporate considerations may have an influence on the nature and extent of associated health hazards. When new plants or processes are under consideration, the corporate industrial hygienist should ensure that adequate controls are incorporated at the design stage. In the 1990s, the profession almost doubled again with the number of CIHs rising from 4581 at the end of the 1980s to 7966 by the end of the 1990s.

Elsewhere in 1995, The International Occupational Hygiene Association (IOHA) hosted an international workshop on certification in Blackpool, the United Kingdom. The goals of the workshop were to further the development and application of occupational hygiene and to enhance movement of occupational hygiene professionals across national borders. To prepare for the workshop, IOHA published an inventory of existing certification/licensing schemes for occupational hygienists in Canada, Italy, Japan, The Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States (53).

2.9 The Twenty‐First Century

American labor changed dramatically during the twentieth century. In the early 1900s, approximately 38% of the labor force was made up of people working on farms. However, by the end of the century, this figure declined to less than 3%. During this time, the service industry was the growth sector, jumping from 31% of the workforce in 1900 to 78% in 1999 (54).

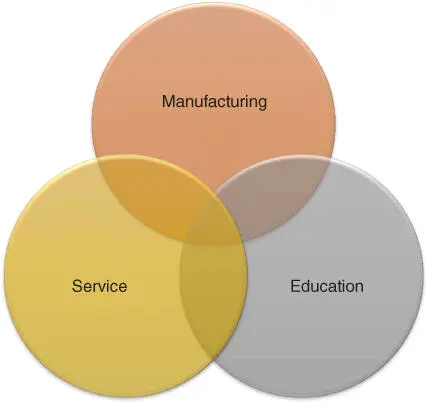

This trend has continued into the twenty‐first century. The workforce which used to be in farming/manufacturing is now mainly in the service industry. Education has also evolved from in‐class learning using textbooks to a diverse learning environment that uses practical training and distance learning tools.

Jobs in the twenty‐first century can be divided into three categories (shown in Figure 1), i.e. service, manufacturing, and education. Based on a report by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics in 2001, the top 10 fastest‐growing industries from 2000 to 2010 included the computer and data processing sector which was projected to increase by 86%, while overall employment was projected to grow by only 15% (55). In addition to the computer and data processing sector, the fastest‐growing industries include residential care with a projected 64% increase, health services with a projected 57% increase, cable and pay television services with a 51% increase, personnel supply services with a 49% increase, warehousing and storage with a 45% increase, water and sanitation with a 45% increase, miscellaneous business services with a 44% increase, miscellaneous equipment rental and leasing with a 42% increase, and management and public relations with a 42% increase (55). These top 10 projected fastest‐growing industries all relate to the service industry.

FIGURE 1Industrial hygienists in the workforce.

The changes within industries and their operating businesses in the early twenty‐first century have resulted in a shift in the skills required for industrial hygienists, often called occupational hygienists. Examples of these changes in the three categories are further discussed.

Many manufacturers that produce goods for daily life have moved overseas. The manufacturing industry in the United States has since evolved to collaborate with more international contractors and personally owned businesses, creating jobs to support the strong relationship between oversea manufacturers and the US market. The fastest‐growing markets include advanced materials; advanced robotics; 3D printing; biotechnology; artificial intelligence; digital design, simulation, and integration; and high‐performance computing. In addition, the Internet of Things is revolutionizing many aspects of manufacturing operations including real‐time production monitoring and improving the accuracy of key metrics including overall equipment effectiveness, production yield rates, and production efficiency. Future manufacturing is predicted to tilt back toward advanced manufacturing nations with robust innovation ecosystems as opposed to the cost‐driven nations of the past.

New emerging technology is powering unprecedented collaboration in the workplace, with many benefits, including increased productivity and the ability to monitor worker risk and exposure. However, changes to the work environment and the introduction of new technology introduce the potential for unknown hazards and unexpected exposures. Advanced and biosynthetic materials are not yet understood in regard to their potential effects on workers, the environment, and nearby communities. It is very challenging for industrial hygienists to protect workers at this stage of development.

The growth of service‐related businesses has expanded to various industries. Contributions by the manufacturing sector are declining in favor of those by the service industry. Labor‐intensive tasks have also shifted from the manufacturing industry, where industrial hygienists primarily served in the past, to the customer service and health care industries in which workers are experiencing a range of hazards while lacking proper protection. These shifts to the taskforce have made safety specialists necessary to new and diverse industries.

2.9.3 Education and Training

Distance learning and professional development training have increased demands for learners, and the scope of learning has broadened and now involves virtual and/or multi‐disciplinary training. Learners are more in favor of learning at their own pace and pursuing their own interests. In the first two decades of the twenty‐first century, higher education has been experiencing an overall decline in enrollment. However, this is not the case for online learning. Education and training for industrial hygiene professionals have been changing in a similar manner. A comprehensive survey on college education enrollment reported that while overall enrollment has been decreasing for an unprecedented 12 consecutive terms in the early 2000s, in 2017 alone, online enrollment grew by 3% to 3.85 million full‐time online learners (56). This report had several key findings, such as the need for career services for online students and more diversified online programs that can satisfy the required training for the environmental health and safety profession. The use of distance learning and the promotion of diverse training have created great opportunities for employed learners from various fields to pursue degrees and/or training in the industrial hygiene, safety, and environmental health fields.

Читать дальше