Part II builds on the foundation in Part I, expanding to multivariable testing. Chapter 6begins Part II with a review of the primary tool used to analyze multivariate tests: regression analysis. Next comes full and fractional factorial designs in Chapters 7and 8, which builds students' understanding of the core issues in multivariate design: interactions and confounding. Fractional factorial designs are useful for building understanding. Next comes custom design, which is ideal for designing experiments in constrained business contexts. The development of software for optimal design has made this sophisticated tool accessible to users, and my goal for Chapter 9is to provide students with a basic introduction to optimal design, while avoiding the algorithmic details that would be more appropriate to a “technical manual.” Parts I and II together form the core of a full‐semester course that is appropriate for more analytically oriented graduate students including MBA students concentrating in analytics and master's of business analytics students.

Not all experiments are technically complicated. There is a great deal of “low‐hanging fruit” in the business world that can be profitably plucked by persons whose knowledge of experimental design does not exceed 2 kdesigns. The goal of this book is to enable students who have taken business statistics to pluck that fruit. In particular, after finishing the first half of this book, the student should be able to conduct an A/B test. After finishing the second half, the student should be able to design, execute, and analyze a 2 kexperiment. To this end, instructors should require students to complete a project where they design, execute, analyze, and report on an experiment. Students benefit greatly from the experience, which helps them see the challenges involved in designing a conclusive experiment and cement the ideas in the book by applying them in practice. A/B tests are easy to dream up, multivariable tests not so much. Hence, Box's helicopter experiment is very important. It is perhaps the only easily executed multivariable experiment available to students that is amenable to screening designs, full factorial designs, and even custom designs. By the end of this book, the reader should be able to execute Box's helicopter experiment Box (1992a) even if the professor does not make it part of the class.

Philadelphia, PA

B. D. McCullough

Without constant support and encouragement over the past three years from my esteemed colleague, Dr. Elea Feit, this book would never have been started, let alone finished. She allowed me to sit in on the business experiments course that she developed at Wharton and brought to Drexel. Despite the publish‐or‐perish demands of an assistant professor's life, she took the time to read and comment on some chapters, suggested many books and articles for me to read, and always had time for me when I ran into difficulties. Her influence can be found in every chapter, but any errors or omissions are mine and mine alone.

I thank Russell Lavery and three sections of STAT 335 students for reading some of the early chapters, and I thank Malcolm Hazel for reading all the chapters.

B. D. McCullough

Bruce McCullough passed away in Fall 2020, just before this book was published. Bruce was an extraordinary scholar and friend, who will be greatly missed. He was fair, direct, true‐to‐his‐word, and expected the highest level of rigor and integrity from himself and those around him. He was also unusually protective of those he took into his care including junior colleagues like me, as well as his wife and children. I'm sure it troubles him greatly that he can't be here in‐person to see us all through.

Based on many discussions we had about the book, I know he felt just as protective towards his readers. He devoted the last few years of his professional life to providing you with a book that would open up the potential of experimentation in business and prevent you from making mistakes when you design and analyze your own business experiments. I hope you enjoy learning from Bruce as much as I did.

Elea McDonnell Feit

Philadelphia, PA

About the Companion Website

This book is accompanied by a companion website:

www.wiley.com/go/mccullough/businessexperimentswithr

The website includes datasets.

We can learn from data, but what we can learn depends on the way the data were generated. When nature generates the data and all variables are free to operate as they will, it is very easy to learn about correlations. Very often though, we don't need to know that price decreases are correlated with increases in quantity sold, but we need to know by how much the quantity sold will increase when price is decreased by a specific amount, and correlations are not up to this task. To learn about causation, we need to restrict the way some variables can act, and this can only be done with an experiment. We don't need sophisticated statistical methods to conduct experiments; the statistics learned in a first non‐calculus‐based statistics course often is more than sufficient to conduct a wide variety of useful experiments. Before conducting any experiments, we need to be very precise about the reasons that observational data are not up to the task of yielding causal insights.

After reading this chapter, students should:

Distinguish between observational and experimental data.

Understand that observational data analysis identifies correlation, but cannot prove causality.

Know why it is difficult to establish causality with observational data.

Understand that an experiment is a systematic effort to collect exactly the data you need to inform a decision.

Explain the four key steps in any experiment.

State the “Big Three” criteria for causality.

Identify the conditions that make experiments feasible and cost effective.

Give examples of how experiments can be used to inform specific business decisions.

Understand the difference between a tactical experiment designed to inform a business decision and an experiment designed to test a scientific theory.

1.1 Case: Life Expectancy and Newspapers

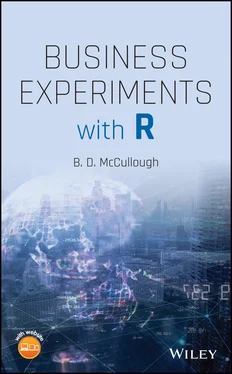

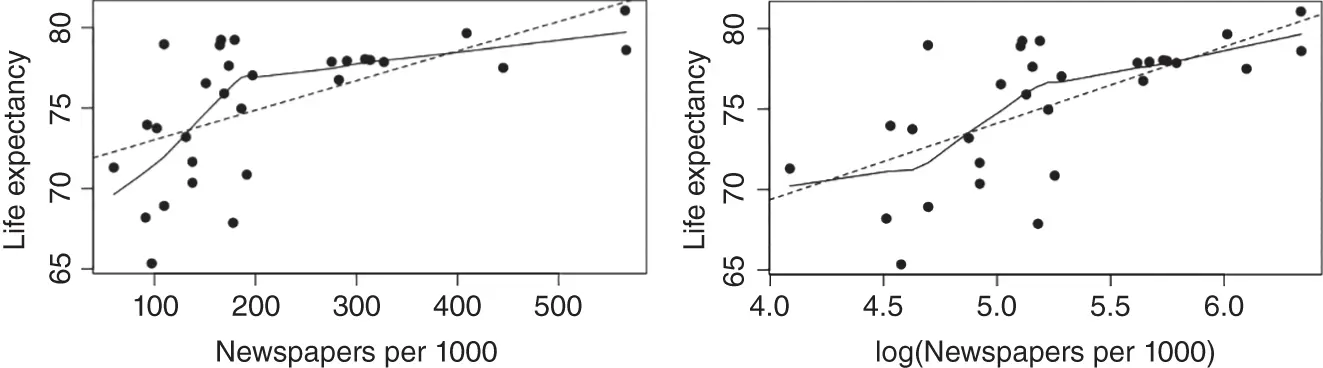

Suppose we are interested in determining the reasons that some countries have long life expectancies while others do not. We might begin by examining the relationship between life expectancy and other variables for various countries. The left panel of Figure 1.1shows a scatterplot of the average life expectancy for several countries versus the number of newspapers per 1000 persons in each country. The data are in WorldBankData.csv. The fitted linear regression line compared to the data shows the obvious curvature, and linear regression is not appropriate. In the usual fashion, linearity is induced by applying the natural logarithm transformation to the independent variable, as shown in the right panel. The log data are still not completely linear, but are much more linear than the original data.

Figure 1.1 Life expectancy vs. newspapers per 1000 (left) and log(newspapers per 1000) (right) for several countries.

Reproduce the above graphs using the data file WorldBankData.csv…

Читать дальше