Collecting and processing statistical data was a time‐consuming and expensive process. Data editing was an important component of this work. The aim of these data editing activities was to detect and correct errors in the individual records, questionnaires, or forms. This should improve the quality of the results of surveys. Since statistical offices attached much importance to this aspect of the survey process, a large part of human and computer resources were spent on it.

To obtain more insight into the effectiveness of data editing, Statistics Netherlands carried out a Data Editing Research Project in 1984. Bethlehem (1987) describes how survey data were processed. The overall process included manual inspection of paper forms, preparation of the forms for high‐speed data entry including correcting obvious errors or following up with respondents, data entry, and further correction.

The Data Editing Research Project discovered a number of problems:

Various people from different departments were involved. Many people dealt with the information: respondents, subject‐matter specialists, data typists, and computer programmers.

Transfer of material from one person/department to another could be a source of error, misunderstanding, and delay.

Different computer systems were involved from mainframe to minicomputers to desktop computers under MS‐DOS. Transfer of files from one system to another caused delay, and incorrect specification and documentation could produce errors.

Not all activities were aimed at quality improvement. Time was also spent on just preparing forms for data entry, and not on correcting errors.

The cycle of data entry, automatic checking, and manual correction was in many cases repeated three times or more. Due to these cycles, data processing was very time consuming.

The structure of the data (the metadata) had to be specified in nearly every step of the data editing process. Although essentially the same, the “language” of this metadata specification could be completely different for every department or computer system involved.

The conclusions of the Data Editing Research Project led to general redesign of the survey processes of Statistics Netherlands. The idea was to improve the handling of paper questionnaire forms by integrating data entry and data editing tasks. The traditional batch‐oriented data editing activities, in which the complete data set was processed as a whole, were replaced by a record‐oriented process in which each record (form) was completely dealt with in one session.

More about the development of the Blaise system and its underlying philosophy can be found in Bethlehem and Hofman (2006).

The new group of activities was implemented in a so‐called CADI system. CADI stands for computer‐assisted data input . The CADI system was designed for use by the workers in the subject‐matter departments. Data could be processed in two ways by this system:

Heads‐up data entry. Subject‐matter employees worked through a pile of forms with a microcomputer, processing the forms one by one. First, they entered all data on a form, and then they activated the check option to test for all kinds of errors. Detected errors were reported on the screen. Errors could be corrected by consulting forms or by contacting the suppliers of the information. After elimination of all errors, a “clean” record was written to file. If employees could not produce a clean record, they could write the record to a separate file of “dirty” records to deal with later.

Heads‐down data entry. Data typists used the CADI system to enter data beforehand without much error checking. After completion, the CADI system checked in a batch run all records and flagged the incorrect ones. Then subject‐matter specialists handled these dirty records one by one and correct the detected errors.

To be able to introduce CADI on a wide scale in the organization, a new standard package called Blaise was developed in 1986. The basis of the system was the Blaise language, which was used to create a formal specification of the structure and contents of the questionnaire.

The first version of the Blaise system ran on networks of microcomputers under MS‐DOS. It was intended for use by the people of the subject‐matter departments; therefore no computer expert knowledge was needed to use the Blaise system.

In the Blaise philosophy, the first step in carrying out a survey was to design a questionnaire in the Blaise language. Such a specification of the questionnaire contains more information than a traditional paper questionnaire. It did not only describe questions, possible answers, and conditions on the route through the questionnaire but also relationships between answers that had to be checked.

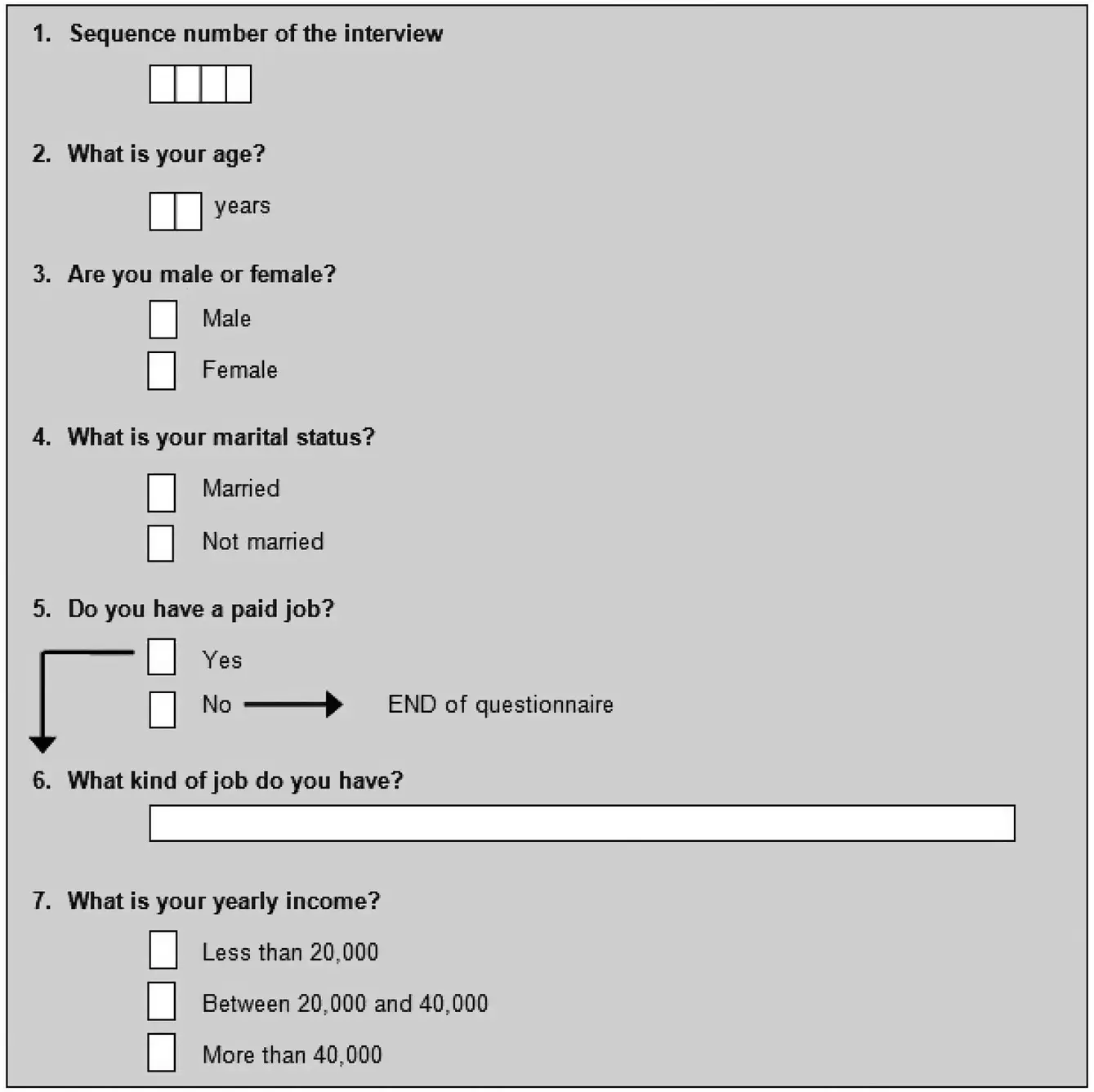

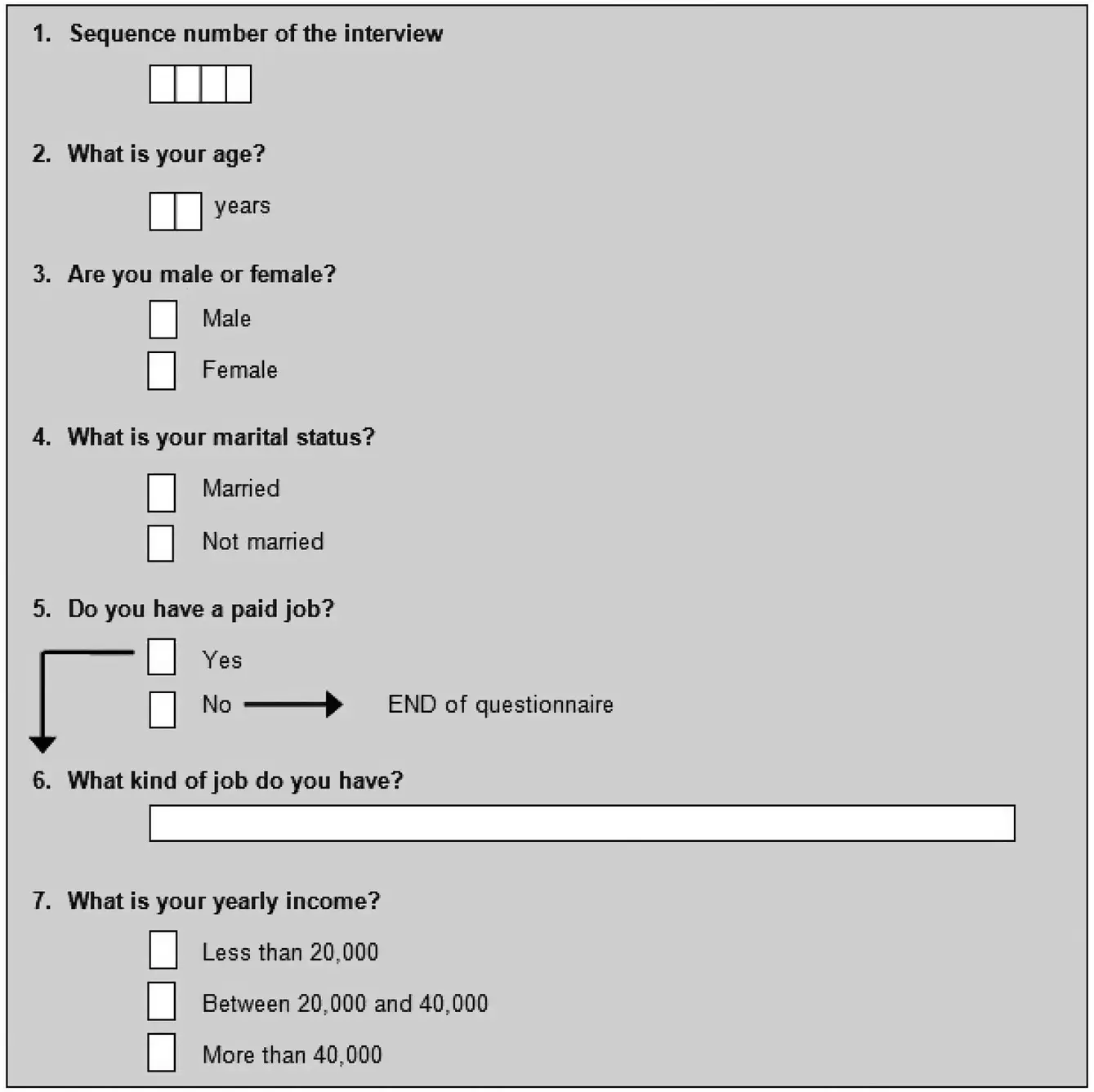

Figure 1.6contains an example of a simple paper questionnaire. The questionnaire contains one route instruction: persons without job are instructed to skip the questions about the type of job and income.

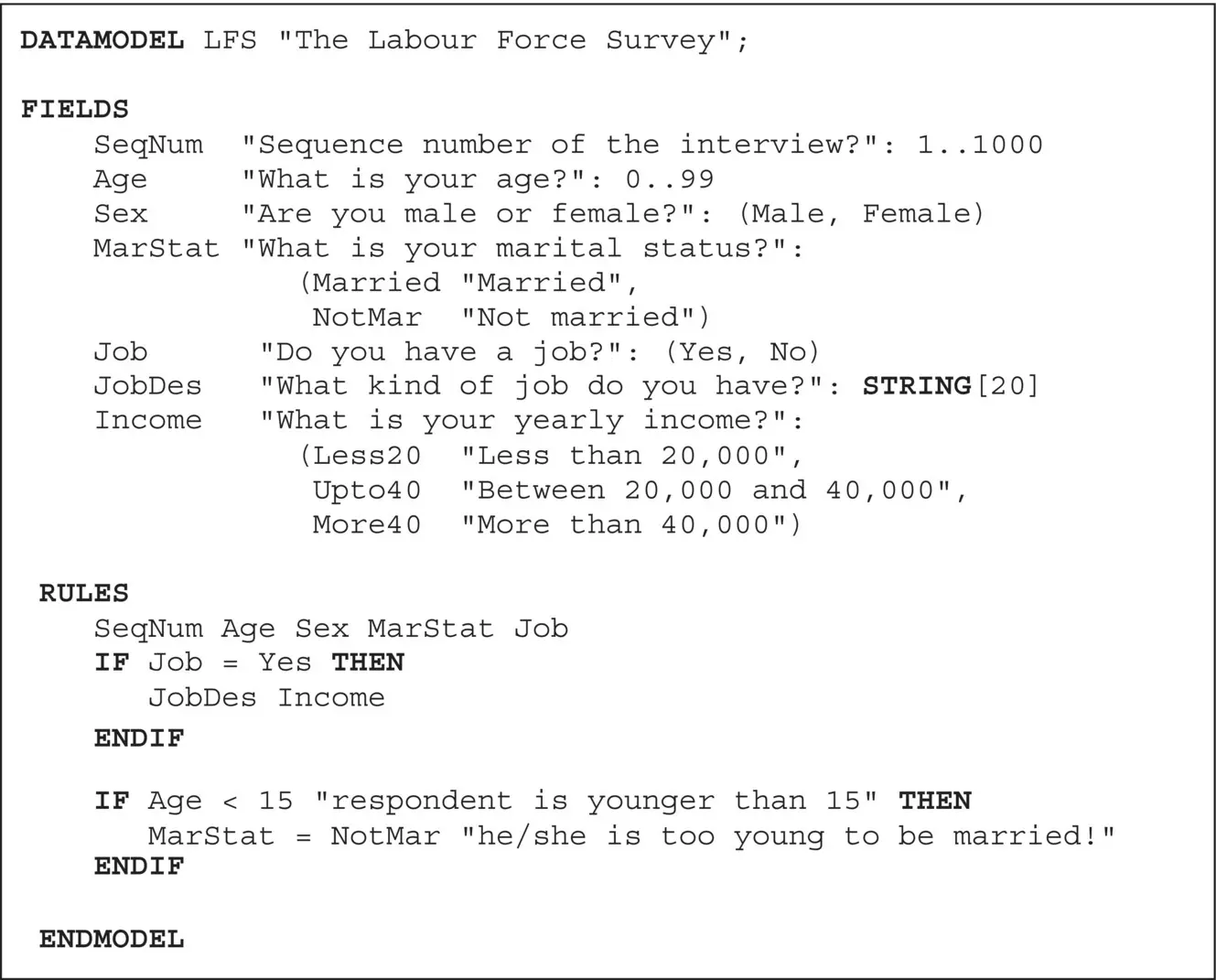

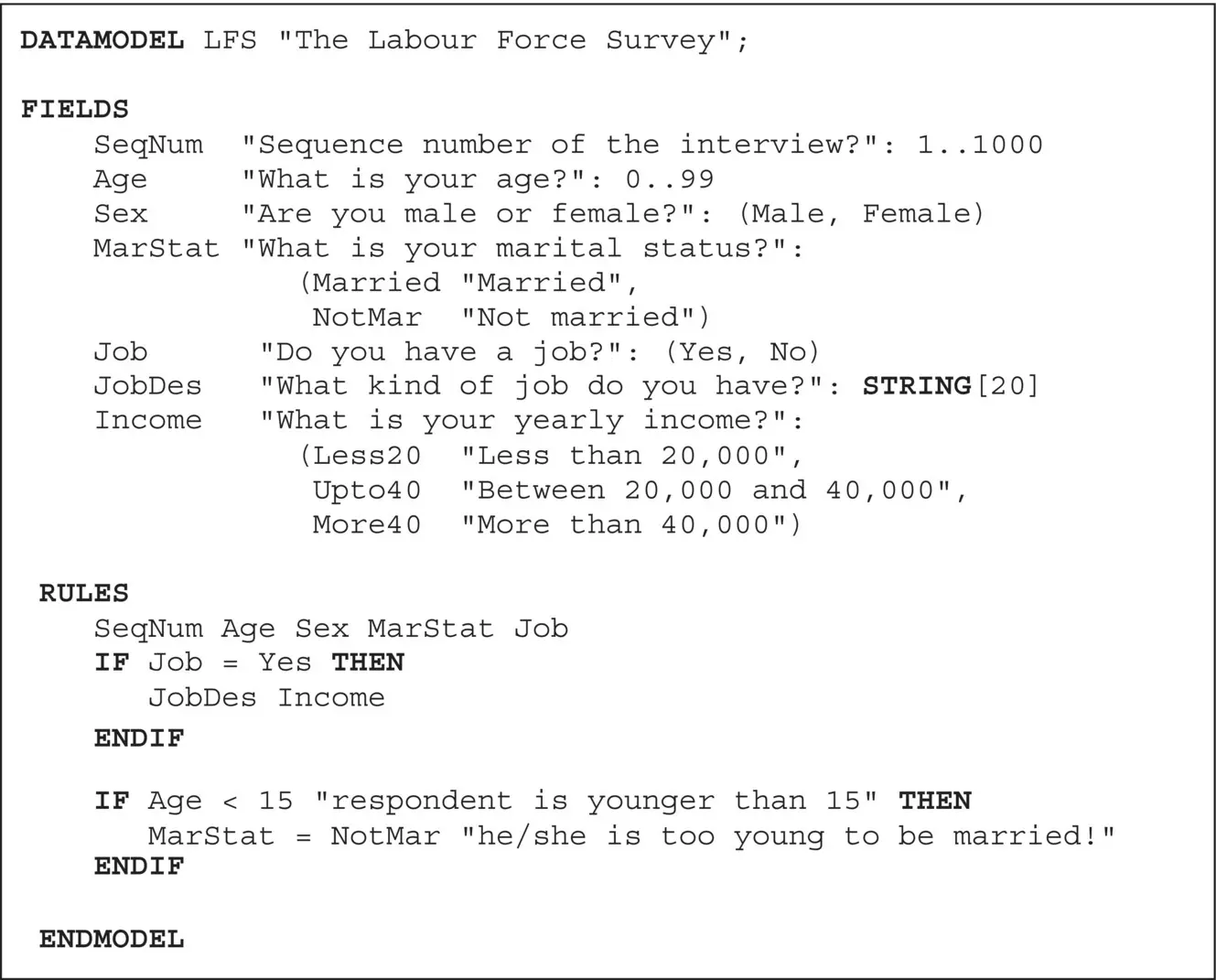

Figure 1.7contains the specification of this questionnaire in the Blaise system. The first part of the questionnaire specification is the Fields section . It contains the definition of all questions that can be asked. A question consists of an identifying name, the text of the question as presented to the respondents, and a specification of valid answers. For example, the question about age has the name Age , the text of the question is “ What is your age? ” and the answer must be a number between 0 and 99.

Figure 1.6 A simple paper questionnaire

Figure 1.7 A simple Blaise questionnaire specification

The question JobDes requires a text not exceeding 20 characters. Income is a closed question. There are three possible answer options. Each option has a name (for example, Less20 ) and a text for the respondent (for example, “ Less than 20,000 ”).

The second part of the Blaise specification is the Rules section . Here, the order of the questions is specified and the conditions under which they are asked. According to the rules section in Figure 1.7, every respondent must answer the questions SeqNum , Age , Sex , MarStat, and Job in this order. Only persons with a job ( Job = Yes ) have to answer the questions JobDes and Income .

The rules section can also contain checks on the answers of the questions. Figure 1.7contains such a check. If people are younger than 15 years ( Age < 15), then their marital status can only be not married ( MarStat = NotMar ). The check also contains texts that are used to display the error message on the screen ( If respondent is younger than 15 then he/she is too young to be married! ).

The rules section may also contain computations. Such computations could be necessary in complex routing instructions or checks or to derive new variables.

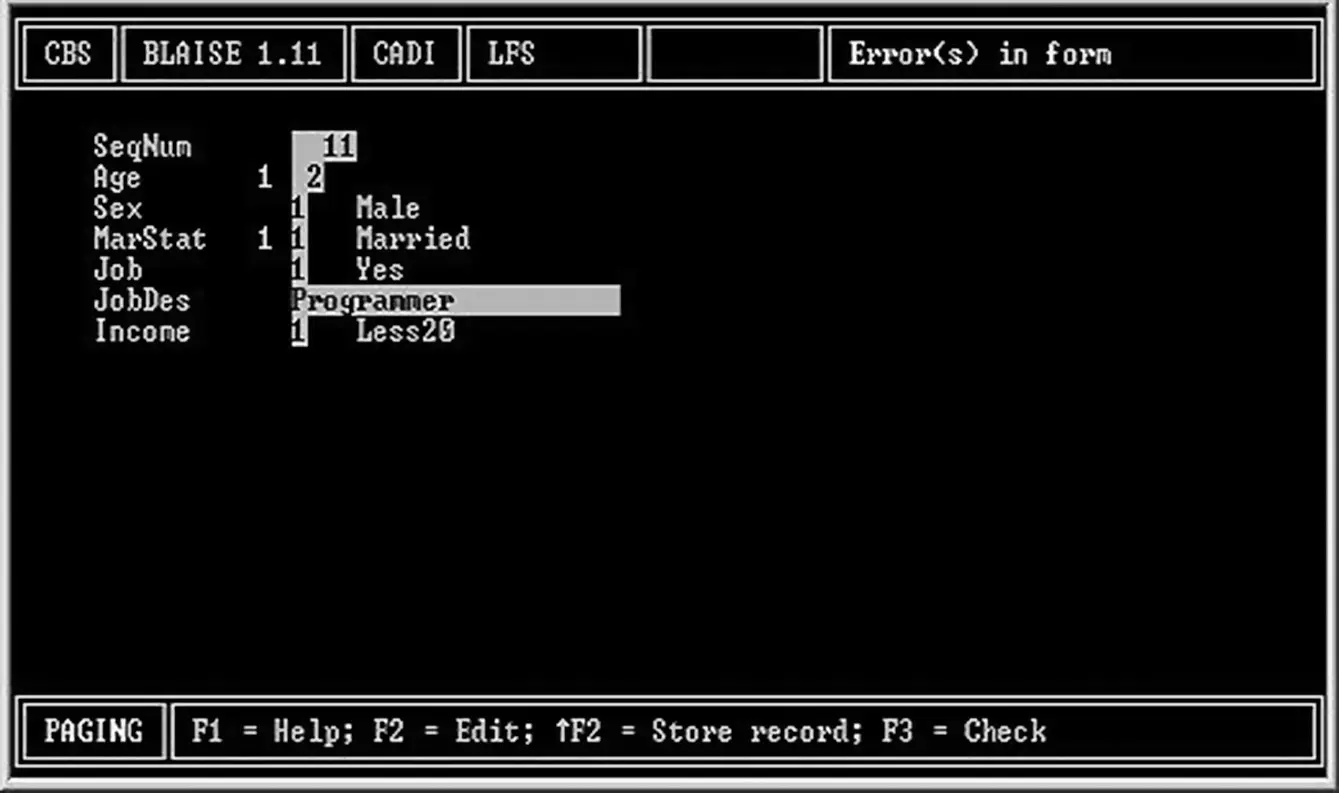

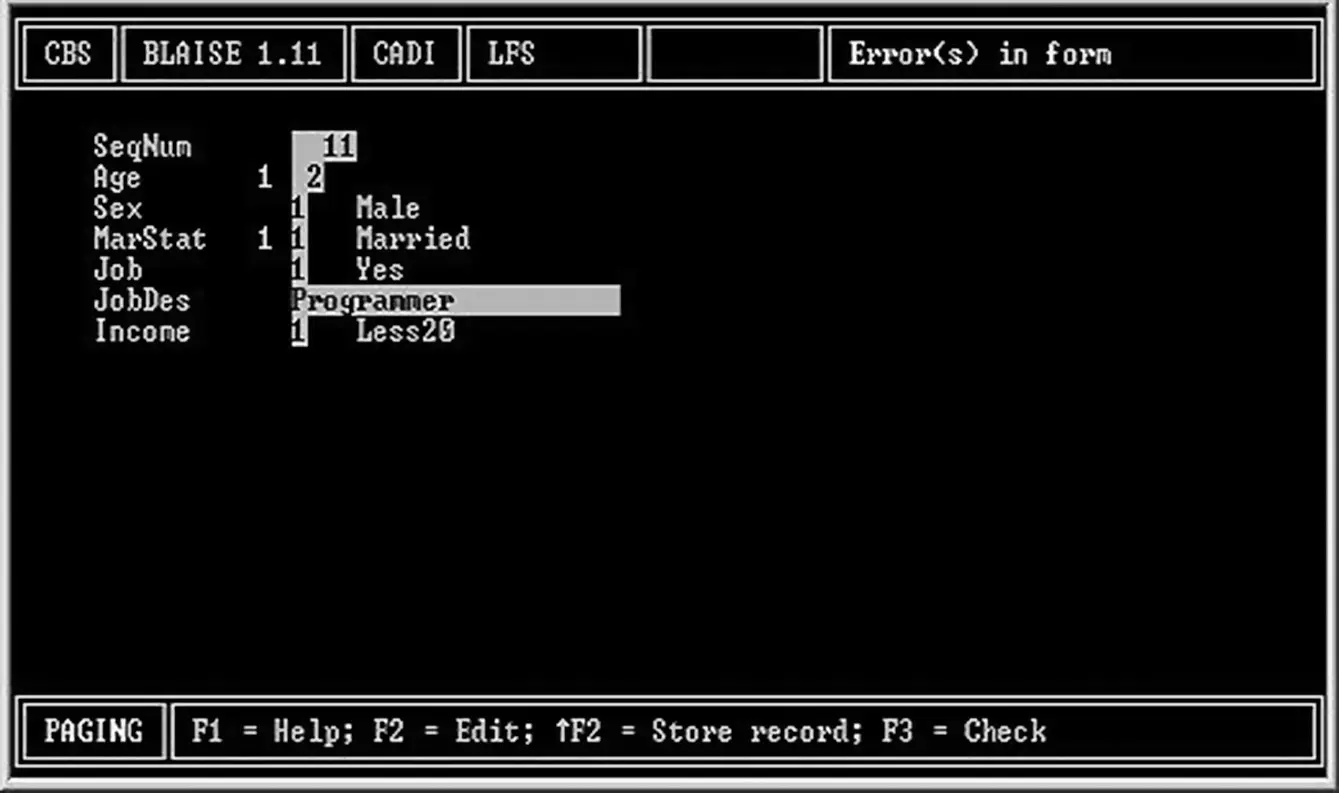

The first version of Blaise used the questionnaire specification to generate a CADI program. Figure 1.8shows what the computer screen of this MS‐DOS program looked like for the Blaise questionnaire in Figure 1.7.

Figure 1.8 A Blaise CADI program

Читать дальше