From Dayan CM et al Lancet 2019 with permission.

A 4‐year‐old boy whose mother has had type 1 diabetes since age 13 years developed thirst, polyuria, hyperphagia, and weight loss shortly after recovering from a head cold. His mother tested his capillary blood glucose with her own meter and found it to be 25.3 mmol/L. His birth weight was 4.1 kg and he was bottle fed with cow’s milk from birth.

Comment: This case illustrates several cardinal features of type 1 diabetes. A positive family history, age of onset <5 years, symptoms beginning after a minor infection, and early exposure to cow’s milk. Birth weight >4 kg is linked to type 2 diabetes in some populations.

The Barts–Windsor study was the first prospective family study in type 1 diabetes and was created by the fortuitous collaboration between Andrew Cudworth (then at St Bartholomew’s Hospital) and John Lister who was the diabetologist in Windsor and who kept a file index of all new cases of type 1 diabetes that he had seen in the district. Around 200 families with a proband with type 1 diabetes and an unaffected sibling were identified and serum collected from as many family members as possible. The findings contributed to what Edwin Gale termed a paradigm shift in the thinking around the aetiology of type diabetes (see 2001 reference below for masterful description). The original objective was to detect the viral culprit for type 1 diabetes. Instead, they confirmed the autoimmune basis of the disease; the clinically silent but immunologically active stage in individuals who had islet cell and GAD autoantibodies years before developing diabetes; and the causative links with some HLA antigens and the protective nature of others. Sadly, Andrew died just as the study was producing its most impressive results, but it remains a fine example of how happenchance and clinical diligence can combine to change our thinking about disease in fundamental ways.

Diabetes Atlas: www.diabetesatlas.org

www.Trialnet.comInternational network of scientists and clinicians exploring cause and treatment of type 1 diabetes

1 Craig ME, Nair S, Stein H et al. Viruses and diabetes: a new look at an old story. Pediatr Diabetes 2013; 14: 149–58.

2 Dayan CM, Korah M, Tatovic D et al. Changing the landscape for type 1 diabetes: the first step to prevention. Lancet 2019; dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140–6736919032127–0

3 Gale EAM. The discovery of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2001; 50:217–226.

4 Gomez–Taurino I, Arif S, Eichmann M, Peakman M. T cells in type 1 diabetes: instructors, regulators and effectors: a comprehensive review. J Autoimmunity 2016; 66: 7–16.

5 Insel RA, Dunne JL, Atkinson MA et al. Staging presymptomatic type 1 diabetes: a scientific statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2015; 38: 1964–74 doi:10.2337/dc15‐1419

6 International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Atlas, 9th edn. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation, 2019.

7 Laugsen E, Ostergaard JA, Leslie RDG. Latent autoimmune diabetes of the adult: current knowledge and uncertainty. Diabetic Medicine 2015; 32: 843–52 doi:10.1111/dme.12700

8 Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyurus E, Green A, Soltesz G and the EURODIAB Study Group. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989–2003 and predicted new cases 2005–20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet 2009; 373: 2027–2033.

9 Patterson CC, Harjutsalo V, Rosenbauer J et al. Trends and cyclical variation in the incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes in 26 European centres in the 25 year period 1989–2013: a multicentre prospective registration study. Diabetologia 2019; 62: 408–17 doi.org/10.1007/s00125‐018‐4763‐3

10 Redondo MJ, Steck AK, Pugliese A. Genetics of type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2018; 19: 346–53.

11 Stiemsa LT, Reynolds LA, Turvey SE, Finlay BB. The hygiene hypothesis: current perspectives and future therapies. Immunotargets Ther 2015; 4: 143–57.

Chapter 7 Epidemiology and aetiology of type 2 diabetes

KEY POINTS

Type 2 diabetes prevalence is set to increase to around 380 million persons worldwide by 2025, with the highest rates in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East, North and South America.

Rates are also higher in urban compared to rural populations and are increasing dramatically in younger age groups, particularly adolescents.

Obesity is closely linked to development of type 2 diabetes through its association with insulin resistance, partly mediated by hormones and cytokines such as adiponectin, tumour necrosis factor‐α and possibly resistin.

A genetic basis has been confirmed by the identification of variants in the transcription factor‐7‐like 2 allele and subsequent development of type 2 diabetes.

The usefulness of the metabolic syndrome as a predictor of diabetes is still debated. β cell dysfunction is present at the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and gradually declines with time.

Prevalence rates and global burden

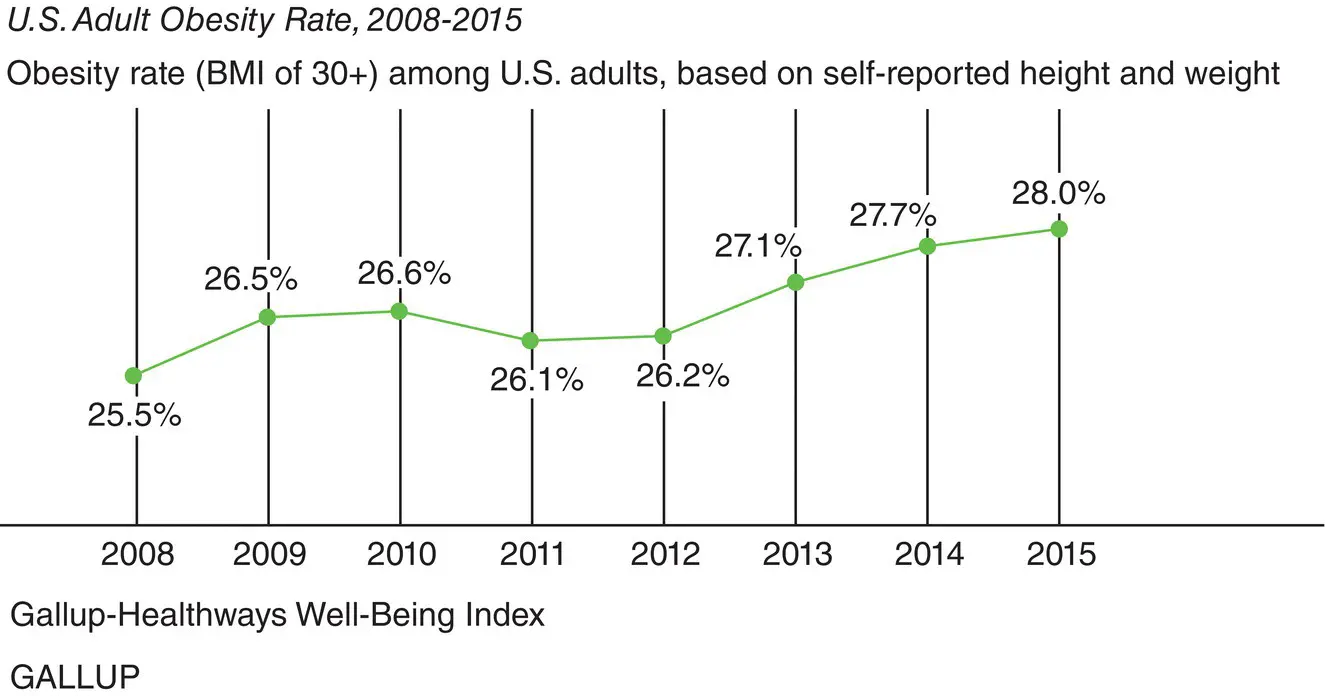

Globally, an estimated 422 million adults were living with diabetes in 2014 (85–95% is type 2). According to the WHO Global Report on diabetes, the global prevalence of diabetes (aged‐standardised) has nearly doubled since 1980, rising from 4.7% to 8.5% in the adult population. This reflects the increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes risk factors, particularly obesity ( Figures 7.1– 7.3). In people with type 2 diabetes, 90% are overweight or obese.

Diabetes prevalence has risen faster in low‐ and middle‐income countries than in high‐income countries. The highest prevalence rates are currently in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East with North and South America close behind ( Figure 7.4and 7.5). Conversion rates from impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) to type 2 diabetes are 5–11% per annum. In terms of absolute numbers, the Western Pacific region (particularly China) will see almost a 50% increase to 100 million people with diabetes by 2025.

The largest number of people with type 2 diabetes is currently in the 40–59‐year age group, where numbers will almost reach parity with 60–79‐year olds by 2025.

Figure 7.1 The relationship between body mass index (BMI) and risk of type 2 diabetes in men and women.

There is however considerable variation between IDF regions and within each region. For example, in the Western Pacific, the tiny island of Nauru has a comparative prevalence in 2007 of 30.7%, whilst nearby Tonga has less than half that rate at 12.9%, the Philippines 7.6% and China 4.1% ( Figure 7.6).

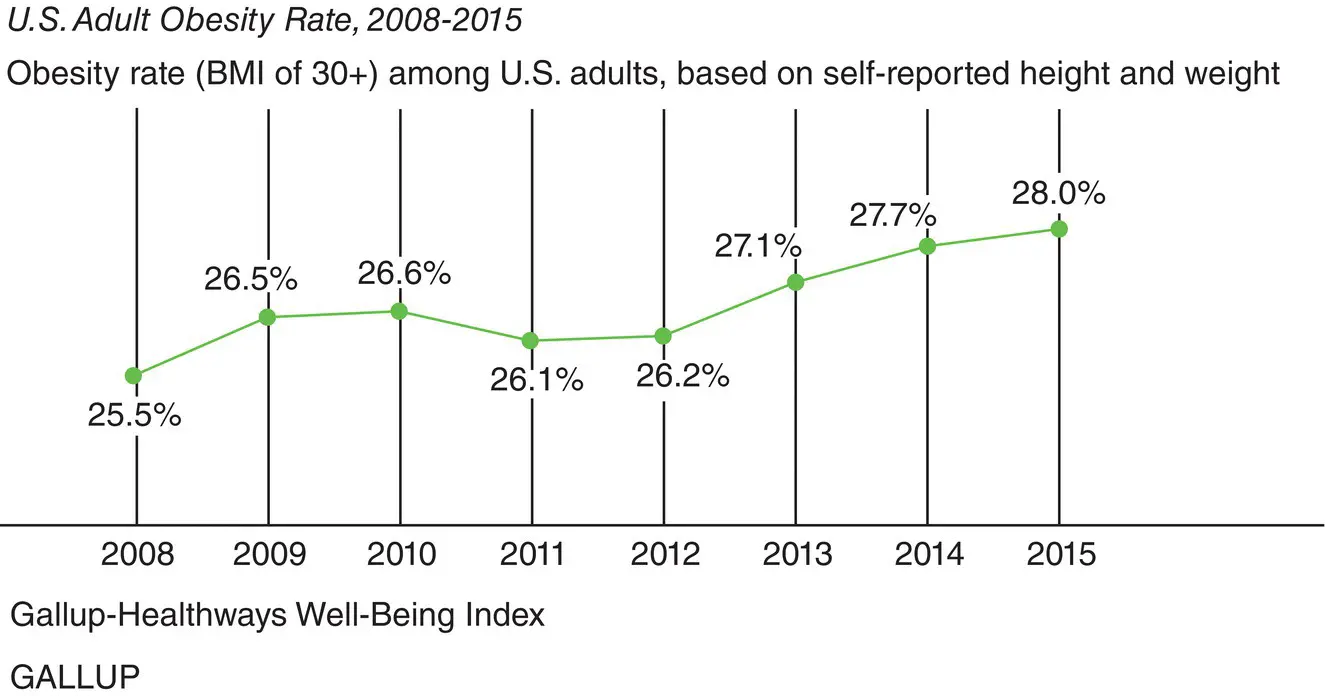

Figure 7.2Rising obesity rates in the USA (2008‐2015) based on self‐reported height and weight and using BMI>30 as a cut‐off. U.S. Obesity Rate Climbs to Record High in 2015, Gallup. © 2016 Gallup, Inc.

Figure 7.3 The rising Prevalence of type 2 diabetes parallels the rising incidence of overweight and obesity. This trend has continued in more recent years. Mokdad AH et al. JAMA, 1999, 282: 1519–1522; Mokdad AH et.al Diabetes Care, 2000, 23:1278–1283.

Читать дальше